The initial connection with a comic book milieu was in the early 1970s. I’d been evicted from my pokey little flat in the World’s End, Chelsea; bath in the kitchen, shared lavatory, paraffin heater, the relentless roar of traffic and the smell of pollution – bad news for someone with an asthma history. However, compared to living on the jungle green slopes of Table Mountain under the shadow of apartheid, it was paradise.

A Xhosa Princess I’d met illegally in Cape Town visited my place searching for another singer from back home. A number of Township girls, beautiful and tough, were amongst the exiles who hung about my flat. In the heady 60s every young person wanted to savour the freedom of Chelsea – the hub of swinging London.

I fell hard for the Xhosa Princess. She called me her husband. Without a spoken word she paraded a nightclub thug around my flat. It was a warning and a threat – I was her man. The Princess had been the Miss South Africa Beauty Queen, and knew how she wanted her men to behave. She felt I had too many white friends, and disapproved of the comic books stacked in growing piles.

I did not want to leave my flat, my home. The landlord did not want me to stay. He had development plans. He summoned the law. I argued in court. I lost.

A friend offered me a rundown maisonette on the shabby periphery of Holland Park. I paid the overdue bills and became a sitting tenant. I acquired a home I could not be evicted from.

I spotted an advert in a local newsagent. Someone in the neighbourhood was selling comics. In a stylish mews, paved with cobblestones and partially in the shade of ancient oak trees, I rang a doorbell. The door opened and I wondered if I had the wrong address.

A suave man beckoned me in. He resembled Alolph Menjou the star of many 193Os Hollywood classics. He dashed off down a corridor and a teenager led me to a room with comic books. Within moments I was crouching, scrambling and selecting like crazy.

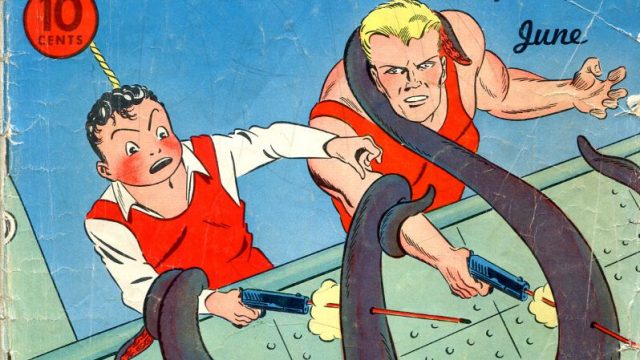

It was soon apparent why the prices were so invitingly low. The comics I wanted were all Fiction House publications from the late 1940s and early 50s of the jungle and adventure genre. Usually the setting was Africa where slavery and oppression were commonplace and the liberator was curvaceous, blonde haired and white skinned, skimpily dressed in leopard or zebra skin bikinis.

Leggy, barefoot and adroit with the whip, these vine clinging Amazons were often accompanied slavishly by a white boyfriend/lover. The details of relationship were murky but marriage was seldom an issue, except amongst the tribal followers worshipping their white goddess. These Jungle heroines were indefatigable and irrepressible but ultimately the blondes were rescued by clean-shaven white males with dark hair. Any resemblance to Tarzan mythology was no coincidence. Sheena Queen of the Jungle easily outshone Lorna of the Jungle but Cave Girl was interesting with a better whip hand. Jumbo and Jungle Comics combined the lot. Kaanga the Jungle King had some fine moments but was never a match for the Queen of the Jungle.

The white hunter complete with jodhpurs and a white shirt beneath a belted brown bush jacket and a pith helmet seemed like an intrusion on that panoply of luscious females swinging the vines.

Outside of the jungle there was often better fare from Fiction House. Fight Comics delved into the spy genre with equally shapely female forms but fully clothed. Planet Comics dwelt on Sci-fi with the underdressed female leads mixing languages, colours and shapes into a heady brew.

The Fiction House war issues had plenty clouds and ghosts but were not as exhilarating or as captivating as the narrative thrust of the more beefcake oriented material. Those airways were a solemn sky bound haven for boys with toys.

There was a limit as to what I could carry away. I bought a lot and came back for more. At fifteen years of age Nick was already an astute veteran dealer but steadfastly honest – which was not something I might easily claim for the dealers I was to come across over the ensuing years. I didn’t care if anybody exploited me; as long as I got what I wanted. I was well paid in the cutting room and as far as I was concerned money was only good for one purpose – comic books. I was hooked. I was a junkie in the truest sense of the word. I was addicted.

That was not the only time I came across overheated Fiction House items. A great many comics from that publishing house were brittle. They were only good for a few readings before crumbling between one’s fingers. Those comic books had spent many an American winter baking alongside radiators.

Nick had bought the comics in Brooklyn when he was in the States with his architect father. The mews house was his dad’s design. His parents were divorced so I never met the mom until years later when Nick got married; probably the best thing that could’ve happened to him. That husband and wife team expanded the Forbidden Planet franchise together in exceptional harmony.

From the start I found Nick to be an unusually straight guy, which is what he was and remains so – kept that way by his astute Oriental wife. As the years passed he was one of the few in the comic book milieu I stayed in touch with for such a long time.

It was an ongoing struggle to decide where I’d met more dubious characters – movies or comics? Perhaps by the end of this I’ll be able to decide.

Nick forged ahead elevating the profile of comics. Had he stuck with film he would probably become a producer. In the comic book world his activities could be described as entrepreneurial. Launching the first Comicon weekend was a major step on the cultural ladder. At the 1971 Comicon I met ebullient Dez, also on his way to becoming a main player in the ascent of comics in the UK.

In the basement of the Waverley Hotel in Southampton Row I got my first introduction to other collectors, and the fraternity of the dealers connected to the American scene.

That Comicon began with me crouched on the floor over a suitcase spilling over with new issues just brought over from Manhattan by Dez, the dealer. Everyone was agog with the latest Shazam and The Shadow. Besides me, no one else seemed interested in the older items, my priority. Getting the imported issues came later.

In the mid 1960s my older sister – living in Great Neck, NY – paid for subscriptions to a slew of publications from Gold Key – previously Dell Comics. The best of that lot was Magnus Robot Fighter with art by the inimitable smooth flowing action packed Russ Manning. Doctor Solar was one of my other monthly favourites along with Shazam the not-so-hot resurrection of Captain Marvel. During the 1960s I had no idea about the vintage market or that there was any such thing as a comic book community.

I was under Dez’s table rummaging, while over me kids were attacking the latest DC and Marvel issues from New York imported by Dez. He was bellowing and barracking, issuing orders and warning the punters to stop shoving and handle his comics with respect. I was encircled by legs and bodies surging back and forth. I banged a foot or two out of my way.

Dez knew everyone and everyone knew him – though not always favourably. I got the comics I wanted from Dez and paid. Looking back as I hurried to the adjacent dealer’s table I saw Dez repacking his vintage items into a cardboard box which he shoved under his trestle table.

A dealer on the far side beckoned me. A wiry, chuckling, robust fellow he insisted that whatever I wanted he would do me a better deal than anything Dez might offer. This was Brian J. There was a manic glint in his eyes which never faded, and a chuckle that went on and on. BJ was an intercontinental truck driver ranging as far as India with an insatiable appetite for vintage comic books. He became my main dealer and made home deliveries. He was a toughie and the boxes he carried up my three flights were bigger and heavier than what was brought by other visiting dealers who were twice his size.

BJ had a good understanding of what my taste in old comics was and he was making tantalizing offers all the time. I’d end up spending more than I had intended.

BJ had some kind of compulsion. There was no logic behind it. At times I was sure he was selling at a loss. He had to sell and I had to buy.

I spent lavishly but I tried to keep to a maximum of 40% of my weekly wage, and I never bought on credit.

I got friendly with BJ’s entire family, including three of his kids as they grew up. His wife was a serene Jamaican lady who barely managed to keep her wild husband calm. She was church affiliated and from an eminent Caribbean political family.

Towards the end of that first day of the Comicon weekend I went back to Dez intending to get more stuff off him. I thought his prices might have dropped. As soon as I approached he warned me that he wouldn’t drop his prices because it was the end of the day.

Subsequently I learnt that Dez had gone home forgetting about The Golden Age box (1938 – 1954) under his table. When he came in the next morning it was gone – stolen. Dez tried to blame the organiser but when it came to it wily Dez was no match for the astute young Nick. He would never forget to take his unsold comics home. Nick never took his eye off the ball; so it seemed over the years.

Decades later Nick commissioned me to write something for him. It didn’t happen but it took off with another publisher. Some years later I asked Nick why he never asked for his money back. He answered that he couldn’t do that because he’d let me down.

I lost touch with Nick but some years later I was in the Shepherds Bush Odeon – now long gone. The cinema was a seedy cavern with a bare cement area between the screen and the front row. There was a constant stream of people strolling or charging across the open area in front of the screen casting shadows onto the film. It was reminiscent of childhood cinema except that it reeked of alcohol and urine. Scuffles were commonplace and occasionally violent. Nevertheless, the shenanigans weren’t a bad as the Biograph cinema with the clattering of changing seats in Victoria which had a terrific repertoire of old films. Along with its grim lighting the Shepherds Bush Odeon felt like a gladiatorial pit.

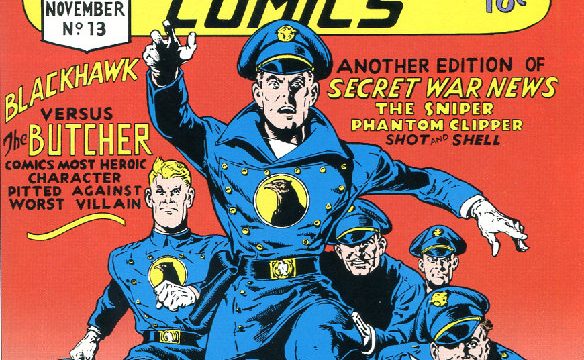

I was on my way to my front row seat when I felt a tug at my elbow. In the dim light I could just make out who it was – Nick. He wasn’t sure it was me until he saw the comic book in the side pocket of my flyboy jacket. We nattered away. He’d completed studying films. He gathered that I’d stuck with the cutting rooms but he’d gone in the other direction – away from film and into comics. He was in partnership with Mike L. They were going into publishing and had a shop – Forbidden Planet in Denmark Street. They were having a party – would I like to come? I was bound to know some people. He said Dez would not be there but I should meet his partner Mike L who collected Airboy Comics, superbly drawn by Kida and written by Charles Biro. In the science fiction genre that combination was unequalled.

I’d met Nick’s partner, the affable slim hipped overheated Mike L, on his way to buy a sports car. I couldn’t see the outgoing Mike L and the restrained Nick getting along forever. It was a business friendship subsequently ended in costly acrimony. It cost Mike L £100,000 in legal fees.

I went to the party. The trim, longhaired Mike L tottering about on high heeled boots sauntered over to me and introduced me to his girlfriend. He asked me who the artist on Golden Lad was. That superhero title had a brief run, and could be considered obscure. I said it was Mort Meskin – one of my favourites. Mike L was delighted. He’d told his girlfriend that I was the only person at the party who’d know that. (I was sure that Nick would have known, but I was flattered).

Years later I confronted Nick about his knowledge about comics. He knew what I was getting at. He admitted he had to downplay that. It wouldn’t do for it to be known, not with the way he was compelled to do business. Historical knowledge didn’t fit with comics. Kids and others needed to believe that it was all new, part of the here and now appeal.

Dez and I really became friends because of Barbara, his girlfriend. She was attractive, affable and at ease with the world. She worked in publicity for Columbia Pictures in Wardour Street. As a publicist she chaperoned many stars: Muhammad Ali suggested they have a baby. ‘It’d be beautiful and it’d be black,’ he’d told her. Instead she had a daughter with Dez. The girl was beautiful but looked nothing like M Ali.

Barbara remains a friend to this day but I still think the champ would have been a better bet. Dez was instrumental in publishing British comics’ luminaries. He launched Alan Moore – that hirsute giant of the worldwide comics’ industry – in the seminal comics magazine Warriors.