I’m fascinated by the V&A’s collection of Jain paintings. Examining them closely, understanding how they were created is fascinating. The manuscripts were originally collected by the V&A for their visual appeal, rather than as religious documents. However, they are also of significant religious and cultural value to the Jain community. Mehool Sanghrajka, current Director of Education at the Institute of Jainology discusses the importance of these painted manuscripts to the Jains here.

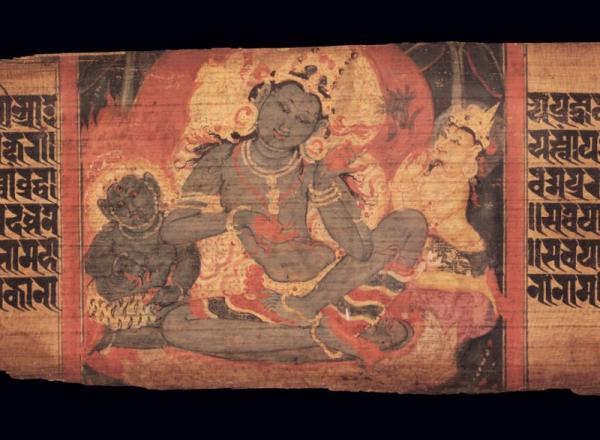

Paper came to India from Iran and was in widespread use by scribes and artists from around the 13th century, but some of the earliest paintings in the V&A collection, like the Buddhist example above, date from the early 12th century and were painted on dried palm leaves. The earliest known Indian text on the practice of painting murals, the Chitrasutra (variously dated from the 4th to 7th century CE), tells artists to think in terms of three dimensions in making their images, and I think that in their innovative use of perspective, foreshortening and modelling, these paintings reveal a sophistication of technique in the 1100s that is not seen in Western painting until several hundred years later.

Paper came to India from Iran and was in widespread use by scribes and artists from around the 13th century, but some of the earliest paintings in the V&A collection, like the Buddhist example above, date from the early 12th century and were painted on dried palm leaves. The earliest known Indian text on the practice of painting murals, the Chitrasutra (variously dated from the 4th to 7th century CE), tells artists to think in terms of three dimensions in making their images, and I think that in their innovative use of perspective, foreshortening and modelling, these paintings reveal a sophistication of technique in the 1100s that is not seen in Western painting until several hundred years later.

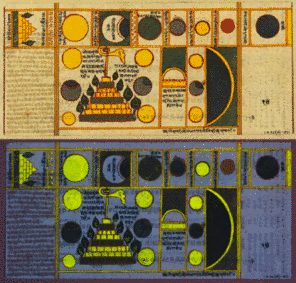

The holes you see at each end of the palm leaf were used to bind the leaves together with a cord. Interestingly, as paper arrived in India around the 13th century, the artist and calligraphers kept the tradition as a decorative motif when painting on paper, leaving spaces in the written text, as you can see below in the 15th century page from the Uttarādhyayana sutra.

Jain painted manuscripts, like a number of other objects in the V&A’s collection have a great deal of cultural and religious value to the community that originally produced them. Although these are museum objects, when conservation is required, as a conservator, I’m very aware of identifying and respecting these values. This can means discussing an object’s handling and treatment with representatives from a community. Sometimes, it can mean adapting conservation or display methods – for example, a copy of the Torah might require the use of Kosher materials or particular manner of display. In the case of the Uttarādhyayana manuscript pages, in keeping with Jain tradition, it means avoiding the use of materials from an animal origin.

The Jain religion dates back at least 2500 years in India, and is fundamentally concerned with liberation of the soul from an endless cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth by the elimination of karma. The Jains hold that all living beings have souls, and non-violence (ahiṃsā) to all beings is a central principle of Jainism. Accordingly Jains are strictly vegetarian.

India is a place where it is difficult to store anything for long before it succumbs to the the effects of humidity, or insects and other pests. In the detail from the painting below, you can see that despite having been a banquet for insects and mice for over 600 years, the paper has been actually been preserved fairly intact. However, looking closely, one can see that there is quite significant damage in painting itself.

Historically, rich patrons gained religious merit by commissioning lavish manuscripts for temples that were often painted with the most expensive pigments (such as gold or lapis lazuli), so it might seem strange that the worst damage to these objects seems to have occurred because of the paints themselves.

The problem stems from the dark green – a pigment that is created from copper. Inherently acidic, some of these green pigments (such as verdigris and copper resinate) can cause discolouration and embrittlement to a paper and textile surfaces on which they are painted. I often encounter green paint in Indian paintings that has dicoloured to a murky brown, but in the worst cases, as in the example below, the degradation of the pigment can lead to the complete disintegration of the the surrounding paper.

To consolidate the loose pigment around these areas in an Indian painting, it would be typical to use a purified gelatine (an adhesive made from bones, cartilage and skin of cattle) or isinglas (a similar adhesive made specifically from the swim bladders of the sturgeon fish). However, after discussions with representatives from the Jain community on the principle of non-violence and the specific avoidance of animal products, we agreed that a synthetic alternative should be used. Perhaps not as effective as an animal-based material, but having the advantage of avoiding the accumulation of bad karma!

We’ll look more into the materials used in Jain paintings and their analysis by the V&A’s Science department in a future post. Some of the V&A’s Jain painted manuscripts (including the 12th century palm leaf above) can be seen in the new displays at the Nehru Gallery of South Asian Art.