Hands that Make, Hands that Hold, Hands that Mend

According to the 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, hands are “man’s outer brain”. They form what we conjure up in our heads: they are the tools of our consciousness. The brain co-ordinates the hand and eye to produce objects just like the portrait miniatures that I have been examining and conserving at the Metropolitan Museum in New York for the past three weeks. I have been thinking about hands on a daily basis but particularly those that created the 16th and 17th century portrait miniatures by Hans Holbein, Nicholas Hilliard and John Hoskins. I have contemplated the hands that made them, the hands that have held them in the past 400 odd years and the hands that conserve them. These objects were created with immense skill and a craftsmanship that is hard to comprehend. The question – ‘how did they do that?’ still resounds….

It is not common-place for hands to be pictorially included in portrait miniatures. However, it just so happens that three of the miniatures I have been examining at the Met do depict the sitters’ hands. Two of these miniatures are by my personal favourite, the left-handed Hans Holbein the Younger. William Roper and his wife, Margaret More were painted in miniature around 1535/36, shortly after her father, Sir Thomas More, was executed.

Margaret holds a book in her hands, showing her dedication to learning, whilst William Roper’s hands hang on to his furry lapels.

These perfectly circular miniatures, measure less that 5cm across. But the amount of attention to detail and finesse packed into this small surface area is immeasurable. The third miniature featuring a hand is that of English diplomat and royalist, Endymion Porter, (1587-1649). It’s painted by John Hoskins, c.1630, nearly 100 years after Holbein painted his miniatures.

Bequest of Mary Clark Thompson, 1923. Oval, 80 x 66mm

Accession Number:24.80.505. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photography Victoria Button. (Cover glass removed).

Hilliard also painted some portrait miniatures that included hands. Among them is Man Clasping a Hand from a Cloud, on display at the V&A, where the hands take on a more symbolic role – in this case, of concord and plighted faith.

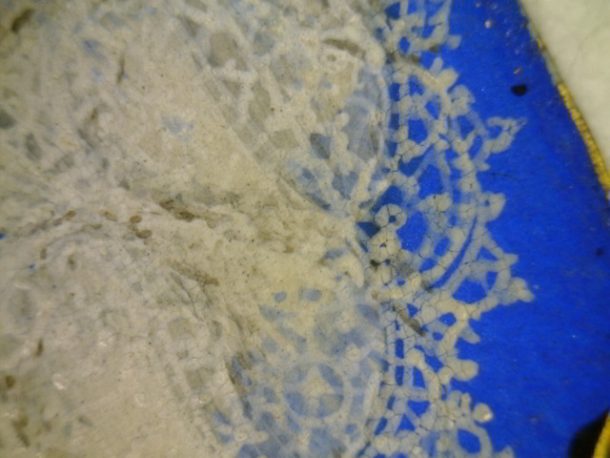

Holbein, Hilliard and Hoskins must all have had a steady hand. Painting a miniature leaves little room for error in a fairly tight compositional space. Stating that he ‘ever imitated, and hold for the best’ Holbein’s portrait miniatures, Hilliard must have had access to them in order to comment. However, Hilliard developed a style all of his own, taking the art of miniature painting to another dimension. Observe the intricacies of the white network of lines for the lace or the gold fluidity of the letters, as well as the mimicking of precious jewels in silver and gold and coloured resins. The white lace collars of his sitters’ costumes are subtly three dimensional, like piped icing on a cake, as seen in the detail from the portrait miniature below.

There is some evidence that John Hoskins (c.1590-1665) was probably trained by Hilliard but he too developed his own style. He originally trained as a painter in oil, which is perhaps reflected in the more painterly (more strokes, less linear) style of his miniatures.The level of detail on all these miniatures, but perhaps Hilliard’s in particular, can only truly be appreciated when looked at under magnification, hence the continuing questions about how they were viewed during the time they were made.

Art historians, curators and conservators often talk about ‘the hand of the artist’ in the quest to attribute an artwork to a specific individual. Left handers, such as Holbein, tend to shade in slanting strokes downwards from left-to-right as opposed to a right-to-left direction of a right-handed person. Such evidence has been claimed to be ‘nearly as reliable as a signature’. However, caution is needed since it has also been suggested that left-handed artists, like Leonardo da Vinci, could have used both hands to draw and write, which makes it slightly more problematic if used as a definitive tool for attribution. It can be more useful and objective to use comparative signs such as materials and techniques that may be particular to or commonly used by an artist. I’m always questioning how to ‘read’ an object. In other words, why does it look the way it does and how can we interpret and describe what we see in order to make it better understood? Accurate characterisation of the materials and techniques that an artist uses is fundamental if that artist’s work is to be understood and interpreted accurately. Consequently, for a conservator, knowledge of the materials and techniques involved in the production of an artefact are important for numerous reasons: as well as providing an understanding of an artist’s working practice, such factors also inform any treatment, display and storage decisions.

A lot of the conservators I work with also are skilled craftsmen themselves – they make things as well as mend things. Conservators are curious about how things are made: this is very important because without that knowledge they cannot conserve. Reconstruction is often an important part of conservation – it aides our understanding of materials, techniques and how they combine to create an object.

Structurally very complex, hands are the most powerful tools we have: they are instruments of gesture as well as a creative force. Fingers have some of the densest areas of nerve endings in the body helping us to ‘read’ objects with our hands and not just our eyes. So at risk of stating the obvious, hands are very important things – not just in the artistic production of objects but also in the understanding and conservation of them. Portrait miniatures are tactile objects. Requiring close examination in order to fully appreciate, miniatures can be problematic to display. Enclosed in their lockets, portrait miniatures were made to be held or worn. Imagine Queen Elizabeth I holding a portrait miniature of herself painted by Hilliard and Holbein handing over the finished miniature of William Roper. Next time you are in the V&A or the Met in New York, take the time to hunt out the miniatures and get as close to them as you can. They are small but there is much to discover.

I just LOVE it when conservators take the time to express such deep contemplations around their work. I would like to quote this as an excellent example of what we should all be doing more of, in my presentation “Sound & Vision” at the Icon 16 Birmingham Conference in a couple of weeks. I assume you have no objection?

Dear Victoria Button,

I do not know how or why I should have your phone number on my ‘Button family” file – 0171 938 8500 – it looks very out of date to me. I must have had it for years. It has only emerged now because one of the genealogists who works on the TVs, “Who do you think you are” is looking into my Button family tree for me. I have just seen your website for the first time, am fascinated because I spent some years painting portrait miniatures, having taught at Cambridge School of Art most of my career.. Anyway, please forgive this intrusion. But I will let you know if you appear on my ‘Button family tree’ when it emerges in 2 or 3 months time. Kind regards and best wishes, Mike Button