by Zoe Allen and Isabelle Rehault-Wills, Senior Furniture Conservators

As part of the redisplay of the Europe 1600-1815 Galleries, several pieces of seat furniture were selected for re-upholstery. Among these was a daybed (W.5-1956), or ‘veilleuse’, by Jean-Baptiste Tilliard (1686 – 1766) (Figure 1). This article focuses on the work carried out on the carved and gilded framework in preparation for upholstery and the discoveries made during treatment.

The Tilliards, father and son, belonged to one of the most important families of ‘menuisiers’ (joiners and chairmakers) working in Paris in the first half of the 1700s and supplied the royal residences with suites of furniture. The Tilliard stamp, ‘estampille’, is located under the seat and the shape and size confirms the Tilliard mark is original. They are known for having worked closely with the famous sculptor, Heurtaud. The fine sculptural ornament found on the bed, particularly the heart-shaped motif, is typical of their style. The condition and visual appearance of the carved and gilded surface was very poor and bore no resemblance to the expected high quality of this important chair maker. The daybed had been over-gilded several times and the most recent gilding had many poor repairs. An initial examination showed no obvious remains of original gilding and a decision was made to improve the appearance of the existing gilding. However, further examination in the studio revealed, under several layers of over-gilding, the remains of an older and probably original scheme that was quite exceptional, with delicate ‘reparure’ and a playful application of matt and burnished areas. The poorly applied over-gilding has completely obscured this fine original detail (Figures 2 & 3).

The stages of chair making in eighteenth-century France involved the rough body being cut by the ‘menusier’, following which the carved ornament would be carried out by the ‘sculpteur’ and then the gilding applied. The materials and techniques of eighteenth-century French gilding are described in several treatises and Jean Felix Watin, for example in ‘L’Art du peintre, doreur, vernisseur’ (1772) describes up to 20 steps. Several layers of gesso are applied, into which finely-carved detail is cut, redefining the carved detail and adding further details, absent from the carving in the wood, to emphasize the ‘rhythm of the ornament.’ This stage is known as ‘reparure’ and was highly skilled work. The cost of the ‘reparure’ could amount to more than one third of the total cost. It is noteworthy that this technique is what characterizes French gilding and each period can be characterized by different styles of ‘reparure’: for example, the Louis XV ‘reparure’ is completely different from that of Louis XVI or the Regency period. The pattern cut into the gesso dictates the areas to be burnished and this intricate play of matt and burnish is another identification characteristic of French gilding. The remains of the original gilding on the daybed is an exceptional example of the complexity and beauty of this ‘reparure’ technique and placement of matt and burnished areas.

Many stages described in historic accounts of French gilding are similar to the techniques of gilding used in other countries, however one step which appears to be unique and specific to French gilding is the use of a yellow foundation layer comprising animal glue and ochre pigment. This is known as ‘jaune d’encollage’ and is usually the base for the matt areas. Gilding elsewhere, however, usually involves applying a foundation layer of yellow bole, a mixture made with clay and animal glue. Both techniques then include the addition of one or several layers of a red bole and these are the areas to be burnished. The ‘red’ bole on the daybed is very dark and has a brown hue. Another unusual aspect of the day bed is that, contrary to the usual French gilding technique, yellow bole has been used rather than the expected ‘jaune d’encollage’. This fact, together with the fine ‘reparure’, makes this daybed truly remarkable in terms of its aesthetic quality. It is a great testimony to its period and few examples of daybeds this size, with what is probably original ‘reparure’ and gilding, can be seen in museums today.

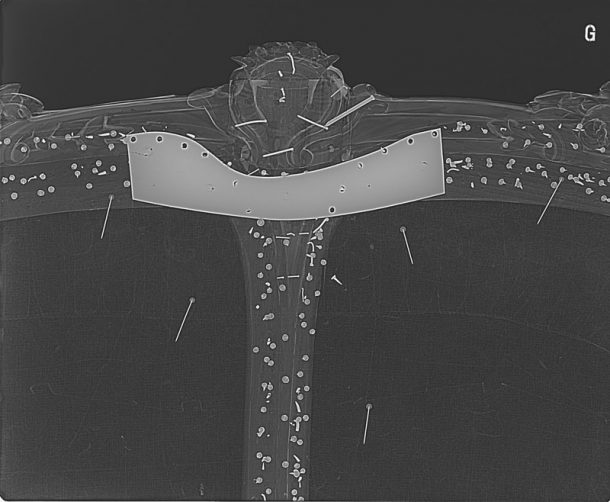

French gilding conservator, Isabelle Rehault-Wills, has many years of experience working with French gilding and this was vital in the interpretation and stripping of the over-gilding. She created a cleaning system to soften the upper layers and with her knowledge of the shapes of traditional tools, ‘fers à reparer’, was able to remove the upper layers to reveal the original decoration. Another detail that made the daybed particularly interesting is the coat of arms of the Marquise de Pompadour (Figure 4). Articles written on the subject showed that it was likely to be a later addition and X-rays and meticulous observation confirmed that this was undoubtedly the case (Figure 5). The shield with the arms of the Marquise de Pompadour, as well as the crown and the right hand side volute of the carving, were of different wood. They did not have any original gilding and some fillings contained lead, unlike the rest of the surface. It is very likely that a heart shaped ornament was removed to fit the coat of arms, probably very similar to the one on the centre of the front seat. Although very little original gilding remains, the majority of the original ‘reparure’ has been revealed together with enough information to indicate which areas were matt and which were burnished. The remains of the original gilding will have an isolation layer applied and regilding will be carried out to emphasize the original techniques, enabling the original craftsmanship to be appreciated once again.

Four specialists were involved in the treatment: Zoe Allen, Senior Gilding Conservator; Isabelle Rehault-Wills, eighteenth-century French gilding expert; Xavier Bonnet, French upholsterer and upholstery historian; and Phil James, Museum Technician, who, together with Zoe, devised a sympathetic and reversible system to allow the upholstery to be attached to the fragile framework without nailing.

Europe 1600-1815 has been made possible thanks to the generosity of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the children of Her Highness Sheikha Amna Bint Mohammed Al Thani, the Friends of the V&A, The Selz Foundation, Würth Group, The Wolfson Foundation, Dr Genevieve Davies, William Loschert, the J Paul Getty Jr Charitable Trust and many other private individuals and trusts.