With the intermittent bouts of hot sun we’ve been having recently, the sight of children (and some adults!) with ice cream smeared across their faces has become an increasingly frequent sight on the streets outside the museum.

Ice-cream and sorbets are now a quintessential part of the summer but it may come as a surprise to some that semi-frozen desserts were being enjoyed in certain areas of Europe over 300 years ago.

In the 16th century, newly wealthy and cultured Italians revived the Roman custom of using snow to chill their wine and food. During the 17th century, despite widespread belief that ice was bad for the health, Italian cooks worked to develop recipes for semi-frozen desserts. This emerging interest in using ice to create new dishes soon spread from Italy to France. Here much effort and ingenuity was applied to preparing ‘ices’, particularly for lavish events at the court of Louis XIV.

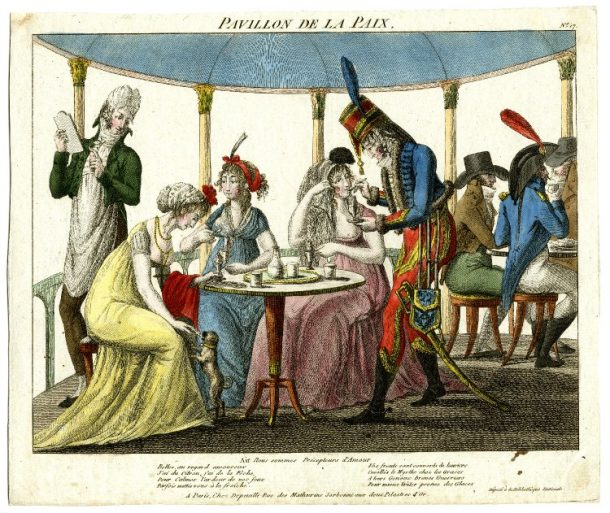

Two types of ice desserts were favoured: glace rare (made from frozen fruit pulp) and fromage glace (made with cream). The first ice cream shop opened in Paris in 1670, followed shortly by the first publication of a recipe (in French) for flavoured ices in Nicholas Lemery’s 1674 ‘Recueil de curiositéz rares et nouvelles de plus admirables effets de la nature’. ‘Ices’ quickly developed into a Parisian fashion to be taken up by the rest of Europe.

In this period, the ability to keep or make anything cold during the summer was the preserve of the wealthy. Creating a year round supply of ice was a laborious process that began in winter and required the use of an ice-house. Making ice cream required a supply of natural ice and they were therefore an ‘unseasonable delicacy’ only afforded by the rich.

During the winter snow and ice would be collected and then stored underground in ice-houses for use throughout the year. The design of these buildings varies, some were underground chambers close to natural sources of winter ice such as rivers and lakes, but others were buildings featuring various kinds of insulation. The ice was not clean and so wasn’t consumed itself, instead it was used to cool food and drinks by being applied to the outside of the container they were in.

Another use of ice was to cool the water to be used in wine glass coolers. These coolers were used by the wealthy when dining in order to rinse and cool their wine glasses. They would have been filled with iced water and each time the diner’s glass was emptied it could be placed in the cooler to be ‘refreshed’ until another drink was required. This wine glass cooler (below) will be displayed in the new Europe Galleries.

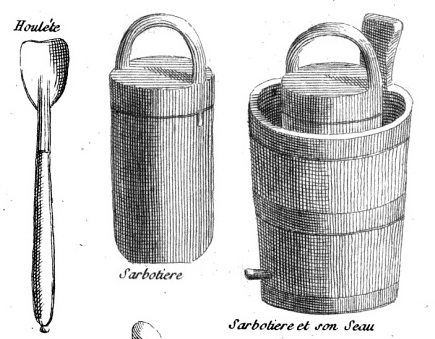

By 1692 there existed at least two cookery books which included instructions for making ice-cream in a domestic environment. Ice would be placed into a large container (or bucket), with salt or saltpeter being added to improve its freezing properties. A watertight basin (the freezing pot or sabotiere) containing the mixture to be frozen would then be plunged into the larger container. The mixture would then be turned and moved intermittently to speed up the freezing action. Instructions for this process are given in Mrs. Mary Eales’s Receipts, published in London in 1718.

‘To ice cream.

Take Tin Ice-Pots, fill them with any Sort of Cream you like, either plain or sweeten’d, or Fruit in it; shut your Pots very close; to six Pots you must allow eighteen or twenty Pound of Ice, breaking the Ice very small; there will be some great Pieces, which lay at the Bottom and Top: You must have a Pail, and lay some Straw at the Bottom; then lay in your Ice, and put in amongst it a Pound of Bay-Salt; set in your Pots of Cream, and lay Ice and Salt between every Pot, that they may not touch; but the Ice must lie round them on every Side; lay a good deal of Ice on the Top, cover the Pail with Straw, set it in a Cellar where no Sun or Light comes, it will be froze in four Hours, but it may stand longer; then take it out just as you use it; hold it in your Hand and it will slip out. When you wou’d freeze any Sort of Fruit, either Cherries, Rasberries, Currants, or Strawberries, fill your Tin-Pots with the Fruit, but as hollow as you can; put to them Lemmonade, made with Spring-Water and Lemmon-Juice sweeten’d; put enough in the Pots to make the Fruit hang together, and put them in Ice as you do Cream.’

The illustration below is taken from Emy’s ‘Art de Bien Faire Les Glaces d ‘Office’ (1768), a recipe book entirely devoted to flavoured ices and ice cream. It shows the basic equipment required to ‘freeze’ the ice cream. Emy’s entire book can be viewed online here.

Another illustration from Emy’s book depicts a group of putti making ices in the French manner. One of them is wheeling a barrow of ice from two conical ice houses, visible in the distance. Two are tending the large buckets (filled with water and salt) which held the freezing pots containing the ice cream mixture. They are ‘agitating’ and stirring the mixture as it freezes.

![Illustration from 'Art de Bien Faire Les Glaces d 'Office’ (1768) © http://gallica.bnf.fr You can view Emy’s entire book online [here] http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k841611f/f9.image](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/cropprint.jpg)

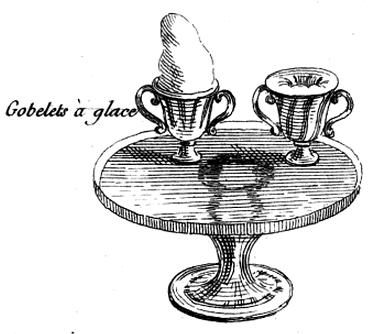

Small cups with handles were developed for eating frozen food. The handles on these tasses à glace, also known as ice cream cups or custard cups, helped to prevent the heat from diners’ hands melting the contents.

Ice-cream pails or coolers were used to serve ice-cream during the dessert course. The decorative French porcelain ice-cream pail shown below would have been used for keeping ices cool for serving at the table. The interior of the ice-pail and its deep cover would have been filled with crushed ice. The ice-cream sat in the inner liner, kept cold by the two layers of crushed ice. The pail and cover are painted in enamels and gilt but the liner (which would have held the food to be kept cold) is undecorated. Porcelain was the ideal material for making ice cream pails because it is impervious to the salt which was added to the layers of ice. This ice-pail shown below was made by the Sèvres porcelain factory in 1778. Records show that ice-pails were made at Sèvres from 1758 onwards. The first ones mentioned in the records are those which were included in a service given by Louis XV to the Empress Maria-Theresa of Austria in 1758. The pail shown above will feature in our new galleries, alongside the wine glass cooler, in a display about ‘Grand Dining’.

Whenever I mention the subject of 18th century ice-cream to people, one of the first things they ask is ‘what flavours did they have back then?’ Appetising and creative flavours created during the 18th century include pistachio, chocolate, raspberry, white coffee and brown bread. Publications by a Mr Borella, who was apparently confectioner to the Spanish ambassador, (England, 1770 and 1772) include recipes for ices made with elderflowers, jasmine, white coffee, tea, pineapple, barberries and a variety of other flavours. Frederick Nutt’s handwritten list of ice cream varieties (dating from 1780) includes Burnt Ice Cream (flavoured with caramel), Burnt Almond, and Damson. His list also includes savoury flavours, such as Parmesan cheese(!).

Suggested further reading: Elegant Eating : four hundred years of dining in style : edited by Philippa Glanville and Hilary Young London : V&A Publications, 2002

Absolutely wonderful, the thought of ‘Brown Bread’ and Parmesan Cheese’ flavours ˚•˚Also I love the ‘Goblets à glace’.

What a wow subject. This is the very first time that I hear the history of the glacé, of the ice cream ! Beautiful story beautifully described. Thank you 4 sharing !