When I have a spare moment, I try and go to our Blythe road premises, to do some research on the Cast Courts in the V&A Archives. Ahead of my visits, my colleagues James Sutton and Nicholas Smith have helpfully been digging information about the building of the Cast Courts, the acquisition of the objects, correspondence with the cast-makers. Among the files I am looking into are the so-called ‘Robinson Reports’, 51 boxes of diligently archived reports John Charles Robinson (1824–1913), this Museum’s very first curator, sent to the authorities of the institution between 1863 and 1886.

In the service of the museum from 1852 to 1867 (first as Curator, then as Art Referee), Robinson spent many years visiting auction houses or roaming around the greatest museums, churches, monuments or palaces of Europe, looking for objects to acquire for the Museum, either in their original form or as reproductions.

Robinson is notably responsible for establishing the V&A as one of the greatest collections of Italian Renaissance sculpture outside of Italy, making some spectacular acquisitions that can now be found in the V&A’s Medieval and Renaissance galleries. In fact, Robinson is considered such an important figure for the V&A that in 2002, a contemporary medal was commissioned to British artist Felicity Powell to commemorate him.

But let’s go back to plaster casts.

I am still plodding my way through the Robinson reports, deciphering Robinson’s chicken-scratch handwriting, having thus far only found the time to go pore over the first 8 boxes. Helped by Annaïg Chatain, a colleague from French museums who spent a few weeks on an internship with us, I’ve already found some very interesting things.

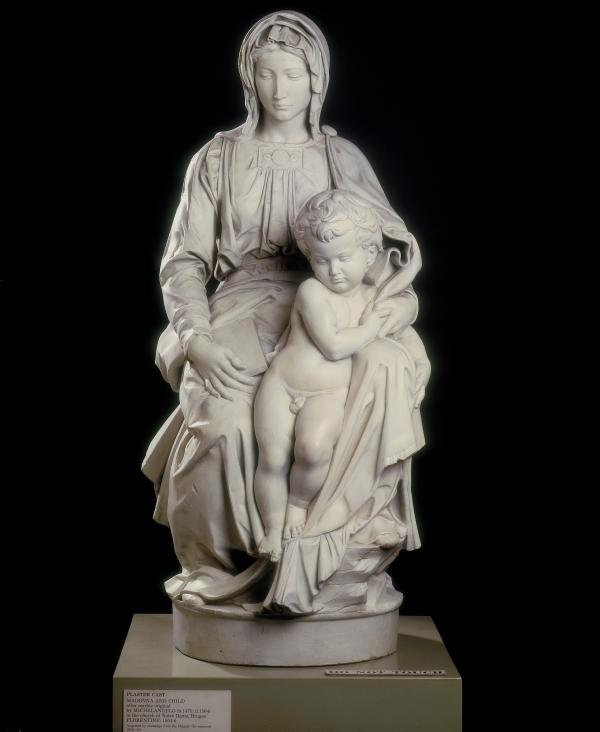

On 4 August 1863, Robinson sent a ‘Report on works of art at Bruges and Ghent, proposed to be reproduced by moulding for the art museum’. In it, Robinson explains why Michelangelo’s Madonna, kept in the church of Notre Dame in Bruges, should be reproduced for the Museum:

“This work has never been moulded nor indeed ever illustrated in an adequate manner. It is nevertheless universally admitted to be one of the most highly finished, complete and most beautiful works of the great master, executed about the year 1500, probably during his first visit to Rome. The marble was given to the church Notre Dame by Peter Mouscron, a Flemish merchant, in 1571, and it is traditionally recorded, that it was purchased by him at Amsterdam, from the captain of a Dutch corsair, who while cruising in the Mediterranean, captured the ship in which the group was being carried from Civitavecchia to Genoa for a church in which latter city it is believed have been originally executed.”

The cast of the Bruges Madonna was not acquired until 1872, as part of an exchange with the Belgian government, but this report nevertheless gives a fascinating insight as to how an object’s fantastic, somewhat romantic, history might have impacted, together with its formal qualities and authorship, in the decision to reproduce it for the Museum.

Robinson was not always enthused by the objects he came across, and another report for instance stated, rather bluntly “I do not think this collection worth attention. […] I went to that town some years ago, to inspect a collection, which proved to be a mere accumulation of rubbish”.

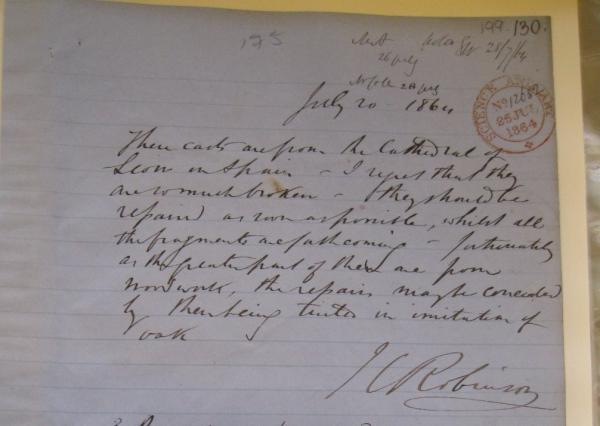

Robinson’s reports are also valuable in recording how the objects (casts or originals) might have come to the Museum, in which condition, and, on a conservation level, how damage was dealt with, as the report reproduced below shows:

‘These casts are from the cathedral of Leon. I regret that they are so much broken. They should be repaired as soon as possible while all the fragments are forthcoming – fortunately, as the greater part of them are from woodwork, the repairs may be concealed by them being tinted in imitation of oak’.

This type of information is very helpful to the conservators now working on the project, as it gives them an indication of the structural weaknesses and former treatments of objects we are now considering for display.

I’m hoping that my colleagues and I will find more exciting pieces of information that might help us understand better the history of the V&A’s collection of cast, and get a sense of the taste and curatorial decisions that were made at the time.