Whilst consulting William Gilpin’s ‘Remarks on forest scenery’, I noticed this statement in the list of plates: “Of these drawings all the landscape-part, which I hope the public will think with me is very masterly, was executed by Mr. Alkin”. The landscape illustrations are unsigned aquatints.

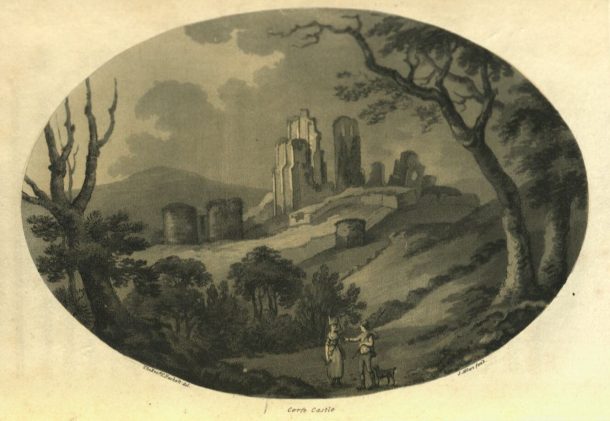

I had recently been cataloguing William Maton’s ‘Observations relative chiefly to the natural history, picturesque scenery and antiquities of the western counties of England’, which contains 16 aquatints by Samuel Alken after T. Rackett (in this case, not only are the plates all signed, but Alken is credited on the title page). Could Alken and Alkin be one and the same? The plates are in a similar picturesque style, and both works are from the same decade.

It turns out that Alken’s work for Gilpin has been well documented. C.P. Barbier has shown (through a study of Gilpin’s surviving correspondence) that he created the aquatint plates for a number of Gilpin’s works between 1789 and 1798.

I was interested to see what other books Alken had contributed to, so searched for his name on our catalogue. This drew a blank, but a little research in standard reference sources showed that he had contributed to over 30 books, of which the National Art Library actually holds twelve.

This demonstrates how illustrative prints can be a hidden collection within a library. Whereas the same prints may often be found in museum print rooms, individually catalogued but divorced from their bibliographic context, they are seldom described at any length in library catalogues. Furthermore, as anyone who has spent any time looking for rare books in libraries will know, catalogue records can vary greatly in their level of detail, even in the same catalogue. If you are lucky, you will find an extensive description with a full searchable listing of all contributors (including illustrators and printmakers); if not, there may be little beyond the simple word “plates” to show that the work is lavishly illustrated with prints by the finest artists and craftsmen of the day. This is especially true of the National Art Library: our online catalogue contains a mix of records ranging from those for books catalogued recently, following full modern standards, to records derived, with little intervention, from 19th century hand written catalogue slips.

The NAL has a particular interest in the arts of the book, so we are keen to draw attention to aspects of illustration, binding and book design (and those responsible for them) in our catalogue records. Printers, publishers, illustrators, designers are all of interest. Although in practice we only have the resources to upgrade catalogue records on an ad hoc basis (for example when books go into exhibitions or when colleagues share the results of their research), when the library catalogue does contain full and detailed records, it can function as a map to the bibliographic universe, revealing the complex network of people involved in the book trade. It can even reveal (as I showed in a previous post) something of the continuing life of books once they have left the shop. Most of all, it can give a fascinating insight into the commercial, intellectual and artistic life of the past.

In my next post I will look at some of the books to which Alken contributed and the people with whom he worked.