According to legend, St. Cecilia lived in Rome around 230AD. She was a Christian who managed to keep a lifelong vow of chastity, despite an enforced marriage to a pagan nobleman. It is claimed that during her wedding St. Cecilia heard heavenly music in her heart, resulting in her status as patron saint of musicians. I thought I’d take this timely opportunity to honour St. Cecilia, whose feast day is 22nd November, by highlighting some depictions of her from the Museum’s collections.

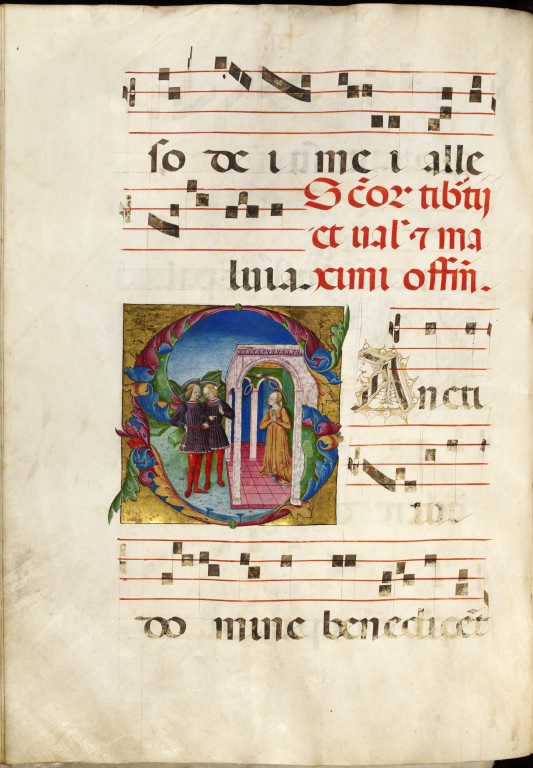

Let’s start with a leaf from a Dominican Gradual (the principal choir book used in the mass), which shows St. Cecilia praying next to her husband Valerian and his brother Tiburtius.

Once they were married, St. Cecilia explained her religious beliefs to Valerian and he was so convinced by her that he agreed to be baptised. He even persuaded his brother to join him in his newfound Christian faith. I like to imagine that’s what they are talking about in this image. There’s no denying their noble status in those fine clothes, but don’t be alarmed: it is said that St. Cecilia earned her sanctity by wearing a coarse goat hair shirt under her robes.

In the Victorian era St. Cecilia captured the imagination of a variety of artists. Here is a painting by Paul Delaroche showing St. Cecilia attended by angels kneeling before her, holding her saintly attribute: an organ.

Delaroche depicts her channelling some divine inspiration, looking to heaven as she plays her tune. Perhaps she is in ecstasy, but I’m not too convinced she is enjoying the sounds she is making.

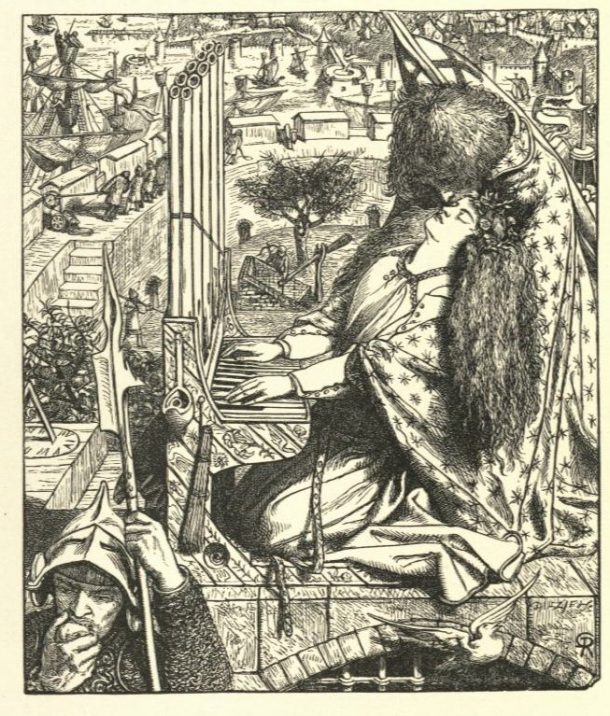

As well as being a model for the Pre-Raphaelites, Elizabeth Siddal was also an artist in her own right. In this drawing by Siddal, St. Cecilia appears to be recording the heavenly music being played by the angel behind her.

Siddal’s drawing was produced as a potential illustration for Tennyson’s “The Palace of Art” in Edward Moxon’s finely illustrated publication of Tennyson’s poetry. In the end, however, her husband Dante Gabriel Rossetti was to gain the commission over Siddal with this eroticised depiction of the saint at her organ, being embraced by the angel as she plays.

Julia Margaret Cameron was clearly influenced by Raphael’s depiction of St. Cecilia when considering her composition for this photograph.

Cameron often used friends and family as models for her photographs. Included in this group is her maid servant Mary Hillier (as St. Cecilia holding the organ) and Mary Ryan, an Irish beggar girl who Cameron had raised alongside her own children. Renowned for her delicate photographic depictions, the simple costumes and plaintive expressions of her models in this photograph are a world away from the typical formality expected of Victorian society.

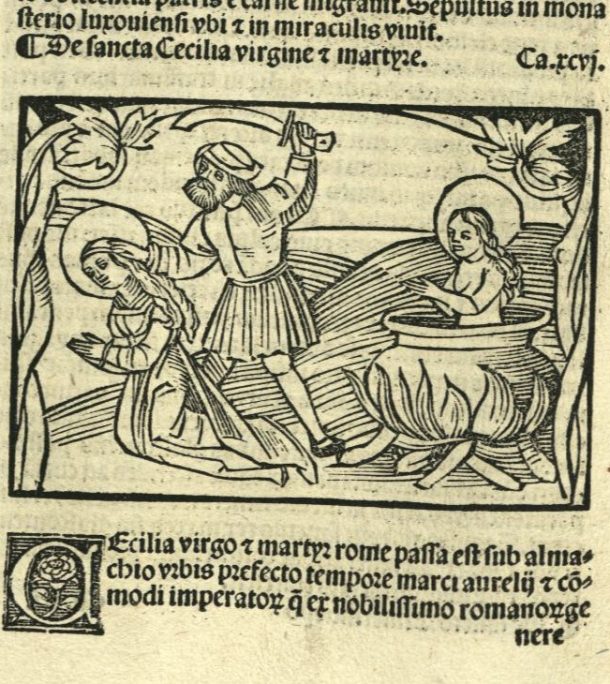

Like many saints, St. Cecilia suffered a fairly grisly death as a result of her enduring Christian faith. Attempts were made to suffocate her in a steam bath, to immerse her in a cauldron of boiling oil, and to decapitate her. Miraculously she lived a further 3 days, giving her enough time to distribute her wealth to the poor.

Let’s finish up with a vivid depiction of St. Cecilia’s demise, from an early printed book about the lives of the saints. Here you can see St. Cecilia twice: being decapitated and boiled in a cauldron.

All of these images are from objects held in the V&A’s Word & Image Department. You are always very welcome to come along to conduct your own saintly research.