This post is by guest blogger Mélissa Evans, a recent graduate of the V&A/RCA History of Design MA course. The following object study draws on research from her dissertation and marks the 250th anniversary of Betty Ratcliffe’s pagoda at Erddig Hall:

Imagine the year is 1767. Betty Ratcliffe has just completed her pagoda model.[i] It is a fascinating object because of the maker’s identity. Contemporaries would have assumed that it was made by a skilled craftsman or a wealthy lady of leisure. Betty, however, was a lady’s maid for the landowner and titled family, the Yorkes.[ii] Artisanal skills were not necessary training for Betty to progress in her career, nor would they have been part of her daily duties. Betty, as a female servant, was unique as she did not fit contemporary categories of craftsmanship. So, who commissioned the model from Betty? How was the object made – and why?

© National Trust Images / Susanne Gronnow

The pagoda was destined for display, as the glass case and stand reveal. Betty’s father, a local clockmaker, very likely assisted with constructing the model’s foundations. Provincial clockmakers sometimes constructed clock cases. [iii] The pagoda structure is made from thick vellum and Betty would have needed a steady hand to attach the minute layers of mother-of-pearl, a luxurious material, onto the surface. Glass pieces of different colours adorn the landscape. [iv] The overall piece must have appeared magical in candlelight!

This intricate object had an affluent, and educated, patron: Philip Yorke – the son of Betty’s mistress Dorothy. The commission sparked some controversy. Dorothy urged Philip to not ‘imploy her [Betty] in that way again…’ as ‘I shall…make too fine a Lady of her…’ [v] Other family letters show the Yorkes’ appreciation of Betty’s skills; however, the ambition of the pagoda made Dorothy uneasy. The latter eighteenth century saw domestic servants gaining greater access to education and looking for the best employment. Being born into this shifting social landscape seems to have made Philip open minded to encouraging Betty’s talent.

© National Trust Images / Photographer

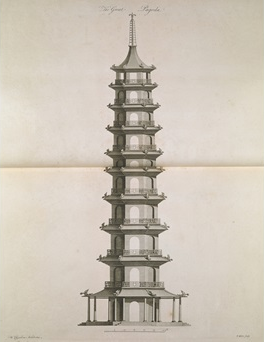

Betty would have needed training before making her pagoda, although her versatile skillset was beneficial. In 1765 and 1766 Betty was producing high-quality drawings, and yet in 1767 she produced a three-dimensional model. [vi] Initial inspiration very likely came from William Chambers’ design for Kew Gardens and Betty would also have needed to see an architectural model. The Yorkes did not own any; however, Betty may have seen the pagodas from Osterley House in London. [vii] Philip visited London several times, and might have visited Osterley for the purposes of the commission.

The choice of subject matter was quite daring as architecture and antiquarianism were male-dominated fields at the time. Nevertheless, unlike Chambers, Betty did not later construct a full-scale structure. Another limitation was that her work was displayed in the residences of Betty’s employers, whereas contemporary male servant-artists had more public careers. [viii] Placing boundaries on Betty’s artisanal career was perhaps a ploy from Dorothy to maintain her authority, and to reinforce Betty’s position.

Betty’s pagoda was used also for the Yorkes’ own agenda. As an ancient piece of Chinese architecture, the pagoda reflected Philip’s interests – he had graduated from Cambridge in 1764, specialising in ancient law and history. [ix] Furthermore, pagodas were ubiquitous in contemporary design. The chinoiserie style was sweeping through Europe helped by imports such as porcelain and lacquer. Historian Hannah Greig suggests that endorsing these trends was a sign of belonging to the ‘beau monde’ – the elite. [x]

© National Trust Images / Susanne Gronnow

Preserving the pagoda was important to Philip. After his mother’s death, Philip personally ensured that the pagoda and stand be ‘carefully packed’ and brought to Erddig, from their London town house. [xi] It survives, still! Philip also commissioned a second model. [xii] Betty’s models tell the story of a designer who challenged conventional norms. The eighteenth century was a time when gender and class were complex, and fluid, constructs. Without Betty’s models, archival records would show her as a loyal servant who produced a few drawings. Imagine if these models had never been commissioned – the controversial patronage of Philip and Betty’s versatile skills might never have come to light.

For more information, please contact the author on melissa.evans@network.rca.ac.uk.

To see what else V&A/RCA History of Design students and alumni have been up to, check our pages on the V&A and RCA websites and take a look at Un-Making Things, a student-run online platform for all things design history and material culture.

[i] Elizabeth Ratcliffe, Pagoda, 1767, Erddig Hall, NT 1147091.

[ii] National Archives, PROB 11/1152, 29 March 1787, p. 325.

[iii] Tom Robinson, The Long Case Clock, (Suffolk: Baron Publishing, 1981) p. 343.

[iv] Merlin Waterson, The Servants’ Hall: A Domestic History of Erddig, (London and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1980) p. 38.

[v] FRO D/E/888.

[vi] Elizabeth Ratcliffe, The Sons of the Duc de Bouillon, 1765, Erddig Hall, NT 1146496; Elizabeth Ratcliffe, Sir Kenelm Digby with his wife Venetia Stanley and their two eldest sons, 1766, Erddig Hall, NT 1146495.

[vii] ‘Elevation of the Great Pagoda’, William Chambers, Plans, Elevations, Sections and Perspective Views of the Gardens and Buildings at Kew in Surry, (J. Haberkorn: London, 1763); Pagoda, 1725-1775, Osterley Park and House, NT 771739.3; Pagoda, 1725-1775, Osterley Park and House, NT 771739.1.

[viii] For information on painter Moses Griffith: Donald Moore, Moses Griffith, 1747-1819: Artist and Illustrator in the service of Thomas Pennant, (Cardiff: Welsh Arts Council, 1979); For a biography of Gervase Spencer: Katherine Coombs, ‘Gervase Spencer, c. 1715-63’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26127 [accessed 01/02/2016].

[ix] FRO/D/E/1542 (177a).

[x] Hannah Greig, The Beau Monde, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[xi] FRO D/E/574.

[xii] Elizabeth Ratcliffe, Temple of Sun, 1773, Erddig Hall, NT 1147092

Awesome design it is.

Its its one of the best design to discover, good and unique to design can be grasped from this post. Its an awesome example and beautiful post.

very cool design