This is the first in a series of blog posts by students of the V&A/RCA History of Design MA programme, to accompany the ‘Building the Royal Albert Hall’ display at the V&A in Room 127 (the entrance to the Architecture Gallery) until 7 January 2018. It was written by Elena Porter.

The display showcases -amongst other things- a model of the façade with decorative details, as well as a cast of one of the terracotta shields designed by Godfrey Sykes.

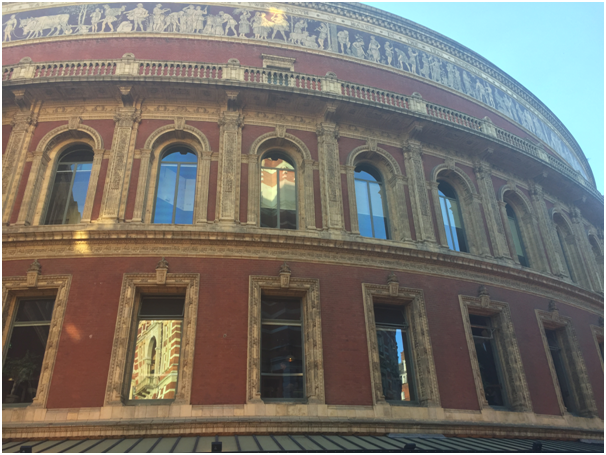

The terracotta decorations of the Royal Albert Hall and South Kensington museums (known as ‘Albertopolis’) make the area distinctive. Yet, when they were under construction, it was hoped that South Kensington might lead a city-wide revival in terracotta. On 4th November 1870, the Building News referred to the construction of the Royal Albert Hall, which had been in progress since 1867 and would be finished in 1871. It remarked that ‘the attempt to decorate brick buildings solely with terra-cotta constitutes to our mind the dawn of a fourth period in London architecture.’[1]

(Image: Elena Porter)

South Kensington: a new dawn for terracotta?

In early-nineteenth century Britain, terracotta was used simply as a substitute for stone, requiring little innovation in building methods.[2] It was not until the middle of the century that terracotta decoration on the scale of the South Kensington buildings was introduced in England. Prince Albert’s plans for a new cultural centre in London required a complex building scheme and a new architectural language. Terracotta was an affordable and easy-to-use material, which suggested historical and artistic connections to Renaissance Italy, while also embodying the potential of a new ‘industrial’ era. It therefore seemed ideal for the new buildings of South Kensington.

(Image: Elena Porter)

Why use terracotta?

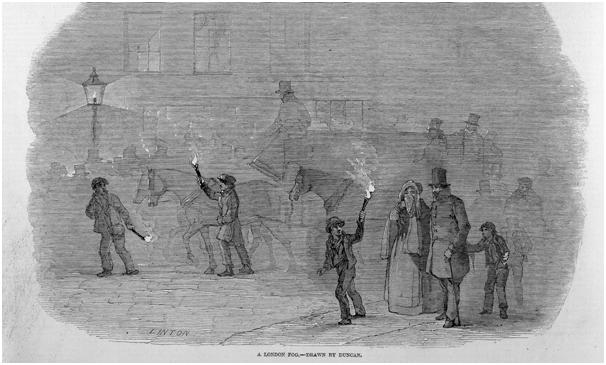

London’s heavy pollution caused something of a crisis in city architecture in the 1850s, as ornamental details were often obscured by layers of soot. Carving stone was labour intensive, and that labour would be wasted if the details of carving would soon be indiscernible because of pollution. Architects therefore looked for a cheaper alternative to stone.[3] Casting terracotta from moulds did not require the extra labour of carving by hand, and therefore saved time and money. It provided a cheap way to introduce decoration, and therefore meaning, to a façade.[4]

The decoration of the Royal Albert Hall was intended to reflect the purpose of the building. This purpose is most explicitly visible in the mosaic frieze, which depicts “the advancement of the Arts & Sciences and works of industry of all nations” for which (it states) the Hall was erected. However, that same purpose is also visible in the general use of terracotta, as a building material that made use of modern construction methods whilst creating a visual connection to Renaissance Italy. This created a link between the advancement of arts and sciences during the Renaissance and Prince Albert’s grand plans for South Kensington.

London’s thick fog, which caused soot to attach itself to façades and obscure architectural details

(Image: The Illustrated London News, Volume 10, 1847: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images (CC BY 4.0)

However, the decision to use the material in public buildings was controversial. It provoked much discussion among architects, including a debate at the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1868. In particular, terracotta’s durability and strength were concerns. Gibbs and Canning, a sanitary-pipe factory in Tamworth, Staffordshire, supplied all the terracotta for the Hall, and defended the use of the material. Mr Canning described the terracotta used for the Hall as comprising ‘pure fire-clay’ and a ‘little grog’.[5] Gilbert Redgrave, who worked on the design for the Hall, remarked in the same meeting that the ‘fire-clay’ used for the Hall was ‘a material of the hardness of which there can be no question’.[6] His comments on the material reflect the vision for Albertopolis as a whole. Redgrave stated:

‘I look upon terra cotta both glazed and unglazed as a material which will eventually make London architecture permanently beautiful and imperishable.’[7]

A ‘permanently beautiful and imperishable’ exterior was appropriate for an area that was intended to be forward-looking, educational and inspirational.

Terracotta was also fitting because of its cultural connections and historic uses. Not only did it echo Italian Renaissance architecture, but it had been adopted by German states as a fundamental building material for their cultural centres in the preceding decades.[8] However, unlike the smooth finish of many Neoclassical architectural decorations, the terracotta decorations of the Royal Albert Hall were made to appear ‘rough’. [9] A finish that showed the signs of manufacture, in its colour and texture, was thought to represent the spirit of Albertopolis. This spirit involved championing new materials, with a lack of pretension, and a sense of honesty in revealing the relationship between industry and design.

Selected bibliography

Primary sources:

Building News, 4th November 1870

Sessional Papers of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Session 1868-69. J. Davy and Sons, London: 1869

Secondary sources:

Christopher Marsden, ‘Godfrey Sykes and his Studio’, unpublished lecture, March 2017

Michael Stratton, ‘Science and Art Closely Combined: the organisation of training in the terracotta industry, 1850-1939’, Construction History, Vol. 4 (1988), pp. 35-51

Michael Stratton, The Terracotta Revival: Building Innovation and the Image of the Industrial City in Britain and North America, (Victor Gollancz: London, 1993)

[1] Building News, 4th November 1870, p.327

[2] Michael Stratton, ‘Science and Art Closely Combined: the organisation of training in the terracotta industry, 1850-1939’, Construction History, Vol. 4 (1988), pp. 35-51, p.36

[3] Michael Stratton, ‘Science and Art Closely Combined: the organisation of training in the terracotta industry, 1850-1939’, Construction History, Vol. 4 (1988), pp. 35-51, p.35

[4] Stratton, The Terracotta Revival, p.14

[5] Sessional Papers of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Session 1868-69. J. Davy and Sons, London: 1869, p.22

[6] Sessional Papers of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Session 1868-69, p.20

[7] Sessional Papers of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Session 1868-69, p.20

[8] Michael Stratton, ‘Science and Art Closely Combined: the organisation of training in the terracotta industry, 1850-1939’, Construction History, Vol. 4 (1988), pp. 35-51, p.37

[9] Christopher Marsden, ‘Godfrey Sykes and his Studio’, unpublished lecture, March 2017