This post was written by Nadia Baadj, Assistant professor of Art History & Rosalind Franklin Fellow at University of Groningen and former V&A Research Fellow

What kinds of secrets do early modern cabinets hold inside, behind their locked doors, hidden drawers, and endless maze of compartments? Far from static pieces of furniture, the examples on view in the newly reinstalled Europe 1600–1800 galleries contain interactive moveable and removable parts, miniature picture galleries and mirrored rooms, and labyrinthine interiors made for concealing objects and documents.

Human interaction was required to fully activate and experience the cabinet. In addition to sight, the sense of touch was essential. As demonstrated in a video accompanying the so-called ‘Endymion cabinet,’ a combination of technical knowledge and physical dexterity were needed to unlock, open, lift, slide, and press various mechanical parts.

In addition to structural knowledge, an awareness of the different strategies used for concealment was crucial to experiencing the cabinet’s complex interior. Take, for example, a typical seventeenth-century Antwerp cabinet on display in the galleries. A key is needed to unlock the outermost doors. This reveals a series of miniature oil paintings depicting the popular parable of the Prodigal Son.

A second key is required to unlock the central painted door. However, a lengthy list of instructions must first be followed in order for the key to work properly in the lock. In this case, certain drawers have to be removed, while in other cabinets architectural elements such as columns move aside to reveal additional keyholes or mechanical devices. It is only with this specialized knowledge that access is granted and the interior reveals itself. In the innermost space of this cabinet is a chamber lined with multiple tiny mirrors that produces an infinite series of reflections when an object is placed on the tile floor.

While the original contents of most early modern cabinets are long gone, an opulent writing cabinet made in Würzburg in 1716 is a rare exception.

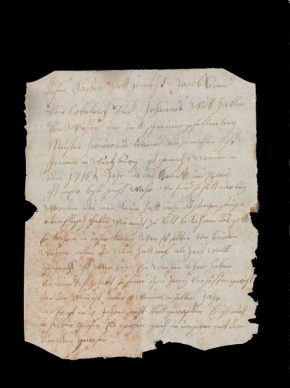

More than 250 years after it was made, the cabinet’s previous owners discovered an intriguing letter hidden under the base of one of the central drawers. Written by the journeyman Jacob Arend, it illuminates the perilous reality of life of an itinerant craftsman. Starvation, poverty, and the prospect of dangerous travel weighed heavily on the cabinetmaker’s mind as he prepared to leave the Würzburg workshop for his next destination. The note’s dire tone contrasts with the sheer extravagance of the cabinet’s materials, which include ebony, horn, ivory, and tortoiseshell.

It is unclear for whom Arend’s message was intended. Its openness and vulnerable emotions, as well as its elaborate concealment suggest that it was not meant to be discovered by the original courtly owner of the cabinet. Whatever the case, Arend ensured that whoever found it would associate his name with high-level craftsmanship and cleverness. A sense of wonder is evoked not only by the exquisite skill and virtuoso artistry displayed on the cabinet’s façade, but also by the complex interior and the secret it contains.

Related links:

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/galleries/level-0/room-6-the-cabinet/

For further discussion of Arend’s hidden letter, see Seyler, Katrin, ‘The Letter in the Writing Cabinet: The Emotional Life of an 18th-century Journeyman’, in V&A Online Journal Issue No. 6 Summer 2014, ISSN 2043-667X, accessible at: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/research-journal/issue-no.-6-summer-2014/the-letter-in-the-writing-cabinet-the-emotional-life-of-an-18th-century-journeyman