These galleries, due to open in early 2015, are the next big gallery development after Medieval & Renaissance. When I took on the role of educator, I wondered how we could refresh our usual package of gallery interpretation and also show some of the social and intellectual changes that took place between 1600 and 1800.

The answer struck me – as it usually does – as I was cycling home. Instead of ‘discovery areas’ discreetly separated from the main galleries, we could do ‘activity areas’ in which the displays and activity worked together to convey our message. The Cabinet, in Gallery 6, would explore the idea of collecting in the 17th century and have hands-on activities for families; the Salon in Gallery 4 would tackle the Enlightenment and be a place for reflection and discussion; the Masquerade in Gallery 2a would have an interactive film and be somewhere for visitors to play and experience some of the social behaviour – and misbehaviour – of the 18th-century masquerade.

We will tell you more about the Salon and the Masquerade in later blogs, but here I will focus on the Cabinet.

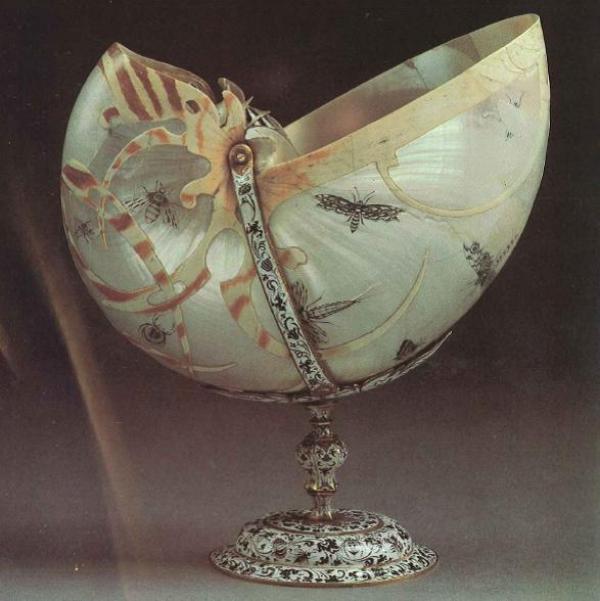

There was a great emphasis on collecting in the 17th century, as a display of wealth and prestige but also as a way of exploring and understanding the world. Anyone with pretensions to scholarship and status – whether a successful pharmacist or a great prince – would have a collection. These collections were enormously varied, but one thing they all had in common was that they combined ‘naturalia’ (things made by God) and ‘artificialia’ (things made by Man, or very occasionally woman) – sometimes in the same object.

The objects might be housed in a small room known as a cabinet, or in a specially made piece of furniture also known as a cabinet. The cabinet was, in embryo, the modern museum.

Nautilus cup, Netherlands, about 1620. Museum no. M.179-1978

There were challenges in developing our Cabinet. The V&A had never before had a single gallery devoted to one all-encompassing idea: normally a gallery consists of freestanding objects and thematic displays. Rotting crocodiles and shrivelled mermaids are not very ‘V&A’. The objects in the Cabinet would be some of the most precious in the Europe galleries. How could we display these in the same zone as touchy-feely stuff for children? And how could we interest children in this material?

We started with a family focus group. In June 2011, we invited fifteen children, aged 5 to 11, with their parents and carers for a tour of the old Europe galleries. By then the galleries were closed and dark, but the children, armed with torches, stickers and quiz sheets, loved the sense of adventure. They also, slightly to our surprise, loved the objects and very quickly ‘got’ them.

The Endymion Cabinet, Paris, 1640–50. Museum no. 1651:1 to 3-185

One of the favourites was the Endymion Cabinet, an imposing and luxurious cabinet made in ebony, perhaps for someone in the circle of Louis XIII. The exterior is black and austere, but inside there is a multi-coloured theatre set with mirrors giving vistas of infinity. When Emmajane Avery, our head of Learning, showed the children this interior there were gasps of surprise and excitement.

Something that had a more mixed reception was the Head of an Ox. This is a weird object. Made for a collector in Padua, it is a marble sculpture of an ox that was found to have an osteoma (a bony growth) in its skull. Carved with disconcerting realism, the ox has bulging eyes, a wet nose and its own skin and hooves draped artistically around the tree trunk pedestal. When asked if the ox was too scary to display, one child took a robust view: ‘Some people might like it. The others don’t have to look at it.’

Head of an Ox, Padua, 1600–1700. Museum no. 60-1882

The photograph shows a surprised ox in Gallery 6 in October 2012. The galleries are now stripped out and we are doing mock ups, in which we bring in objects and position them according to the architects’ plans.

The ox will form the focal point of the gallery. Around the walls will be cabinets of all shapes and sizes, including the Endymion. On the walls will be paintings and sculptural reliefs. In display cases there will be intriguing objects made from rare and precious materials: gold, silver, rock crystal, amber, ivory and shell.

Behind the ox you can see a bright blue plastic globe and an open book. They are positioned on what will be the activity table, where children (and adults) can explore aspects of 17th-century collecting.

This idea of activity table was inspired by paintings of 17th-century cabinets, which show tables piled high with scientific instruments, sculpture, shells and books. Our globe, showing the world as it was understood at the time, will show where rare materials and objects came from.

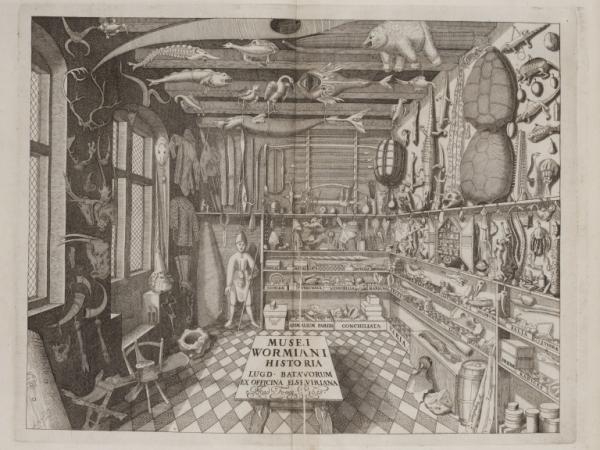

Frontispiece from the Museum Wormianum, 1655. National Art Library: 86.B.11

To the left of the globe is an open book, one of the key objects in the Cabinet. It is the catalogue of a collection belonging to Danish physician called Ole Worm. When he died in 1654, his collection was bought by the king of Denmark and integrated into the royal art collection. It included shells, bones, fossils, stuffed animals, weapons, snowshoes and a mechanical human figure. Beside the Ole Worm catalogue we will have a ‘Spot the …’ activity to encourage visitors to explore this ‘chamber of wonders’.

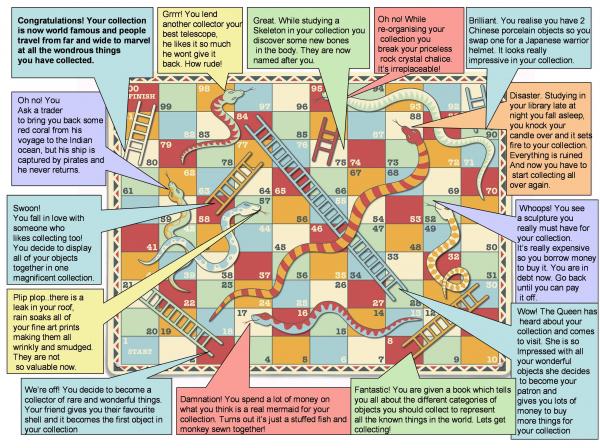

Prototype, adapted for the Cabinet by Nadine Langford

Further along the activity table there will be a snakes and ladders game, brilliantly adapted by my colleague Nadine Langford to show the highs and lows of collecting. ‘Congratulations’, it says to the winner, ‘You collection is now world famous and people travel from far and wide to marvel at all the wondrous things you have collected’. Or, ‘Blast! You have spent a lot of money on what you thought was a real mermaid for your collection. Turns out it’s just a stuffed fish and a monkey sewn together.’

Over the past year we have been testing these activities with children. The snakes and ladders game is a big favourite, but one little boy, a budding scientist, was entranced by the Ole Worm catalogue.

We tested the Cabinet on adults too, inviting Professor Maurice Howard of Sussex University and Professor Joanna Woodall of the Courtauld Institute to have a look at our mock up. Their response was supportive and stimulating. Joanna particularly liked the activity table, saying that in the 17th century people really did draw, handle, discuss and study objects in their cabinets.

Ole Worm said of his collection that its purpose was to allow visitors ‘to see with their own eyes’. In a digital age that is our purpose too.