This post was written by Ingrid Lunnan Nødseth, a PhD student at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim who recently completed a Visiting Research Fellowship in the V&A Research Department.

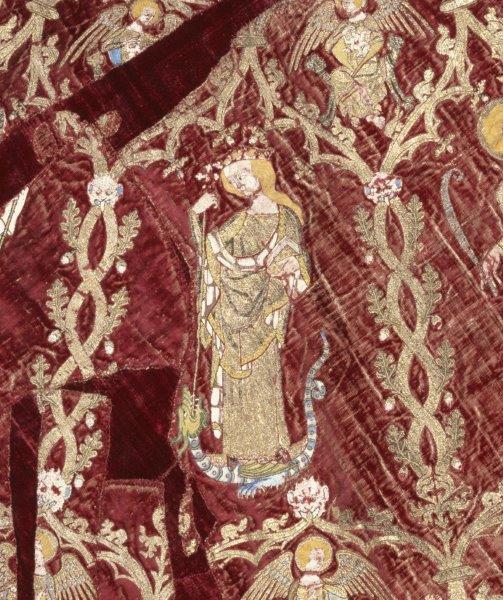

With the upcoming exhibition Opus Anglicanum: Masterpieces of English Medieval Embroidery (opens Saturday 1 October 2016), the V&A has sparked renewed interest in the genre. In the first exhibition in more than half a century devoted to the subject, the Museum highlights an often overlooked or forgotten art and craftsmanship from the Middle Ages. The masterpieces on display include this beautiful vestment known as the Butler-Bowdon cope (c. 1330 – 1350) with scenes from the Life of the Virgin and figures of saints and apostles, made in exquisite needlework and costly materials such as velvet, silk and metal threads, precious pearls and beads.

Many pieces were exported to mainland Europe. Pope Innocent IV (1243-1254) famously commissioned numerous examples, having noticed the magnificent vestments that English bishops were wearing. Less well known is the fact that English embroidery also flourished in the Norse world. A small but remarkable collection of Opus Anglicanum dating from the late 12th / early 13th centuries can be found in Iceland, Norway and Sweden. These fascinating fragments of gold embroidery are a testament to the close connections between England and medieval Scandinavia at the time. One extraordinary example from this group is the set of Holár vestments (from the Icelandic Hólar Cathedral).

Several objects on display in the V&A illustrate the close connections between medieval England and the Norse community, among them an intricately carved crozier of walrus ivory with traces of gilding, known as the Wingfield-Digby Crozier (late 14th century).

St Olaf with his axe. The Wingfield-Digby Crozier, Norway, late 14th century. Museum Number: A.1-2002 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

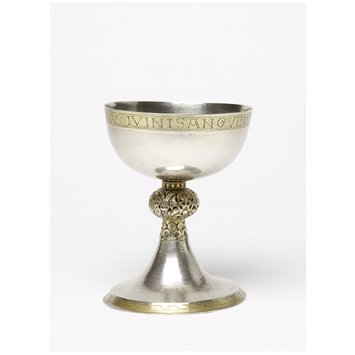

This rare example of Scandinavian ivory carving shows the figure of St. Olaf with his axe entwined in foliage. Whereas this crozier was probably brought from Norway to England, a silver-gilt chalice from c. 1200 is believed to have been commissioned in England for the Cathedral in Holár, Iceland, probably around the same time as the Holár vestments.

The Holár Chalice, Iceland/England/Norway, ca. 1200. Museum Number: 639&A-1902 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

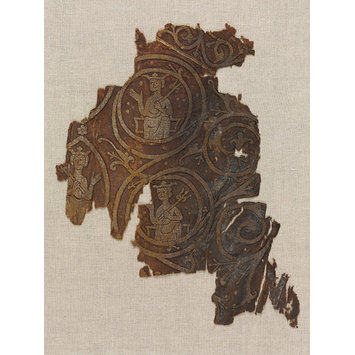

A fragment of gold and silk embroidery, consisting of the upper part of two liturgical stockings or soft knee-length boots worn by a bishop, preserved in the Archbishop’s Palace Museum at Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, Norway, is another rare example of Opus Anglicanum in medieval Scandinavia.

The technical features suggest that this work was made in England in the late 12th century. Part of a pontifical stocking thought to have been worn by Walter de Cantelupe, Bishop of Worcester, now in the V&A textile collection, has similar scrollwork decoration (c. 1220 – 1250).

Part of a pontifical stockings, worn by bishop Walter de Cantelupe, England, 1220-1250. Museum Number: 1380-1901 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

It has been suggested that the Trondheim stockings were acquired by Archbishop Eysteinn Erlendsson during his exile in England in 1180-1183. Archbishop Eysteinn was a reforming bishop with great influence in medieval Scandinavia, and close contacts with England and France. He knew Thomas Becket from his studies in St Victor in France, and during his years in England, Eysteinn acted briefly as abbot of Bury St Edmunds (and possibly Lincoln). He also participated in electing Waltham Bishop of Winchester in 1181. Exquisite embroideries in costly materials, such as the Trondheim stockings and the Holár vestments, were important means for ambitious bishops to portray themselves as God’s vicars on earth. Maureen Miller argues in her excellent book on early medieval vestments of Northern Europe (Clothing the Clergy. Virtue and Power in Medieval Europe, 2014) that this ornate and expensive style of clothing was consciously employed by the reform movement of the 11th century to reinforce and strengthen clerical hierarchies in their struggle for independence and integrity.

Written sources on the subject of English embroidery in the Norse world are scarce, but an interesting entry in the Liberate Rolls (Henry III’s household records) is worth mentioning. In 1233, Henry III paid the goldsmith Adam of Shoreditch for a “Mitre pretiosa” for the Norwegian archbishop, Sigurd Eindrideson. Such an expensive and elaborately decorated mitre was only worn on special occasions. These glass panels from the V&A’s collections show such precious objects, with pearls, gold and precious stones.

Glass fragment depicting a jewelled bishop’s mitre, a ‘mitre pretiosa’, England, mid 15th century. Museum Number: C.386-1915 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The background for this gift-giving may have been an unfortunate incident a few months earlier, when King Henry’s sheriffs confiscated the Archbishop’s ships by mistake. Equally, this precious textile may have been a diplomatic gift. The new Archbishop was the most powerful man in Norway at this time, as King Håkon had not yet secured his position and still relied on Sigurd’s support to reign.

The presence of English embroideries in Scandinavian collections testify to the popularity of Opus Anglicanum in the Norse world. Nothing comparable to the Butler-Bowden cope is preserved in Scandinavian museums or cathedral treasuries, this does not mean that such pieces did not exist in medieval Scandinavia. Extant objects, although fragmented, certainly tell us about close connections between the English and Norse communities in the Middle Ages, especially between bishops and high-ranking clergy. For this elite, expensive and elaborate pieces were means of staging and transforming themselves at a time when the Church struggled to liberate itself from secular control and implement the Gregorian reform movement in the Christian North.

English medieval embroidery is really outstanding. As I see here, fabulous design and a perfect sewing work. I’m really impressed by these awesome designs.