This interview took place between fashion designer Iris van Herpen and Leanne Wierzba, co-curator of What is Luxury?, at the Victoria and Albert Museum in late-July 2015.

Leanne Wierzba: Thank you for agreeing to meet with me to discuss your work, in particular the dress that you have loaned to us for What is Luxury? – designed in collaboration with architect Philip Beesley for the Voltage Haute Couture collection. I am so pleased that we were able to include this piece, as it has facilitated our discussion of luxury as innovation, experimentation, risk-taking and time investment in the making of objects – all principles that the dress and your design practice more generally embody so well. Could you start off by telling me a bit more about the concept for the collection?

Iris van Herpen: The inspiration for the Voltage collection came from Carlos Van Camp, an artist from New Zealand who is known for his experiments with the Tesla Coil. He will actually stand on top of it, using his body as a conductor for the electricity. He has worked on many of the details about how to do this. I was in contact with him while working on the collection.

At the same time, I also went more into my own body. I was reading a lot about the way that we use the energy inside of us. We have a massive amount of energy trapped in our bodies that we are not really that good at accessing. So, on the one hand I was doing research into technical aspects of electricity and how we use it in our daily lives, and also in a work of art. At the same time, I had questions about whether human beings can get any better about finding these levels of energy that we have inside of us.

How does this research translate into clothing?

I think there is an interesting relationship between clothes and the human body, in that wearing different clothing can definitely create some form of energy. It is psychological and very strong. I used to dance a lot, so movement, energy, its transformation within the body and how you can control this has always been very fascinating for me. With Voltage, I dived into that subject directly.

Would you say that the biggest barriers to accessing this energy are psychological?

Totally – and also our daily lives are not really based on movement anymore, which has a lot of influence on our psychological health. I find this true in my own life – I used to dance a lot but now it’s much more inside my head. I’m hoping to find that balance again, because I think there is a lot of energy and also knowledge inside our movement and bodies. I feel that it is an important balance and that a lot of people are missing it.

The placement of signature embellishments across the entire surface of the Voltage dress appears to make the dress quite challenging to sit in. Is this an inbuilt incentive to keep moving?

Well, it is easy to sit in, in the sense that it is light and flexible. However, if you sit in it, the back will be flat. The piece is really not made to be perfect. Each of the individual shapes is meant to be a little bit different – they are so delicate that they need to shift about a bit. This really helps to create the feeling of energy and movement. It gives the impression of static electricity.

The catwalk presentation pushed this concept of electricity even further. It was quite dramatic. At the centre of the room, a model stood on top of a Tesla Coil and you could actually see the electric discharge shooting from her body like lightening. What does the experience of standing on the Tesla Coil feel like?

I only know from her experience. I still want to do it myself but it wasn’t the right timing. She said it was one of the most beautiful things that you can ever experience. You can literally see the electricity coming out of your nose and even out of your eyes. The way she described it was really inspiring. It was a special moment because the show was her first time, and it was also the first time that we made a garment for that purpose. We worked on it for two or three months.

Did she not have to rehearse extensively in advance of the catwalk?

There was only one rehearsal the day before the show. But you work toward it for a number of months, and then there is no way back! The first time, Sarah started to cry because what she saw was so beautiful.

Voltage was also really special because it was the first time I collaborated on a collection with Philip Beesley. The collection before, Hybrid Holism, had been inspired by his work. When he saw it, he contacted me.

That is incredible synergy. It’s almost as though Hybrid Holism was your siren call.

Maybe unconsciously. I would have never expected to work with him. But there was such a match that we still work together today.

You regularly collaborate with architects and artists on your collections. This seems to enable you to experiment with ideas, materials and techniques that are relatively alien to most fashion practitioners. Your collaboration with Beesley seems to hold a particular significance.

There are different types of collaboration. They are often very functional. Usually I collaborate with architects because I want to work on a certain file and they are specialists on it, so there is a really fixed goal. But with Philip, we didn’t have a specific purpose in mind. It was just that basic fact that we were really fascinated by each other and by each other’s work. There is so much to find in each other’s process that it’s much more like the foundation for a long-term collaboration.

So, you would describe your collaboration as quite experimental?

It’s very hands on. We can literally sit together with materials and if nothing comes out of it, it’s fine because we learn so much from working together. A lot of our experiments don’t end up in a collection or in a piece of art. Of course some of them do, but it’s really driven by excitement and curiosity. The material development is always continuing. Ideas might slowly evolve over time and mature until they come out again at another point. That’s why it is ongoing even if there isn’t a specific project.

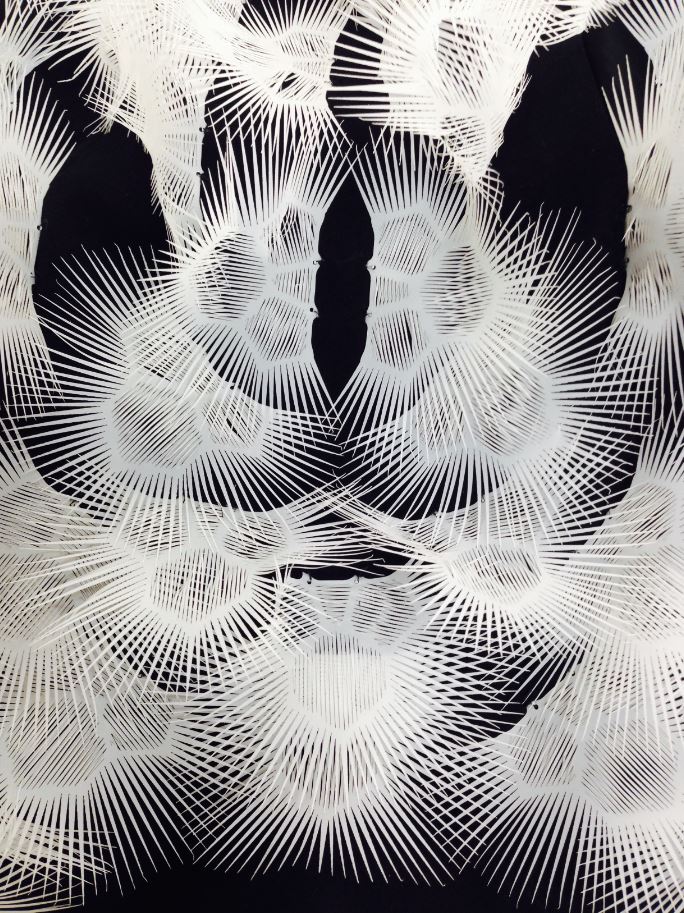

The mesh structures on the Voltage dress seem to come directly out of the lexicon of Beesley’s own architectural practice, in which natural motifs and synthetic materials are used to build immersive environments that act like living, breathing things.

He creates a lot of leaf-like structures in his work. However, the shapes on the dress were specifically made for the collection. They are really inspired by the voltage aesthetic, or at least that is my interpretation of it. They are soft and very delicate but also have this spikey touch to them that adds an edginess. They have been made to visualise this abstract idea of electricity, movement and energy. Of course, they also have a delicate touch and feathery feeling, so I really tried to find that balance.

That’s interesting to hear, because I’ve noticed that people tend to interpret them in a few different ways. One colleague exclaimed how the dress would not have been anything unfamiliar to an Edwardian lady – the polyester laser cut forms replace feather trim. Your work seems to bring together almost opposing influences, from nature and science to traditional dressmaking and new technology.

I’m very inspired by nature – of course, because it is the creation all around us. At the same time, I am not very interested in using materials directly from nature. I am not a very exotic person and wouldn’t use feathers or precious stones. I like using them as an inspiration, but then recreating them myself. I think this piece is a good example of that. It has some sort of feathery touch in it, but I would never apply actual feathers onto a dress, because it would not be my own language.

I am also very inspired by technology – well, ‘inspired’ is a big word. It definitely is part of my work. It’s maybe not directly the inspiration but it is one of my tools. Like the various handcrafting techniques that I use – technology is equal to that. They are both part of the toolbox that I use to create the ideas and concepts. It’s not that one of them is more important – I think that they are very blended in my way of thinking.

Last year you came to London to launch an artwork produced in collaboration with Jólan van der Wiel. At the time, you expressed interest in continuing to produce artwork alongside your fashion practice. I’m curious to know how this has evolved. Do you see yourself as an artist, a fashion designer or a designer more generally? Do these distinctions hold any interest for you, or do you not frame your work in that way?

For me, it is not so important to give words to these things. However, it is also important to define the area in which you specifically work. I see myself as a fashion designer, but I also think that today you don’t only need to be creating clothes. I definitely create space for other disciplines. If I look at the people around me where I work, they are more and more defining their own areas. An architect is not always an architect anymore, and a designer is not always thinking about furniture.

Today, it is so easy to connect to others and this really helps to break open routines. I do like to focus myself toward fashion, because I feel that I still have a lot freedom within that little bubble. But I do need to break free at some points, to really open up the way that I go through my process. Because, for example, when I work with Philip or Jólan, they bring different skills and their process – in terms of timing and development – is so different to fashion. It really helps me to find more space in my own work.

In the exhibition, we have organised objects into small groupings in relation to a specific term. Your dress falls under ‘non-essential.’ For me, this term is a bit of an oxymoron, as there is something fundamentally human about wanting to push beyond what is merely essential for survival or general well-being. It seems like an essential quality of your work that it is risk-taking and pushes beyond expectation. Is this something that is a necessity or luxury for you?

Well, that’s an interesting conversation, because what is essential and what isn’t? I think it’s so personal. For one person what is essential could be totally nonsense for another. For me, my work and fashion in general is essential. I like playing with it because that’s where the border between fashion and art is shifting. In its essence, fashion is a product and it’s functional, but it has also been interpreted so widely that it can go in any direction. I think that freedom is important to take. In my own work, I often will start a dress without a clear idea of the end result and purpose in mind. It’s not really about that; it’s about the process of getting there.

When I present my collection, it’s for people. But the process of getting there is a very personal one, and at that stage its only purpose is me and the people around me. So that’s a really strange shift, between what’s non-essential for others and very essential for myself to the other way around, where it becomes nonsense for myself, which I like. I think that’s a beautiful thing about fashion as well, that it creates its own life after I have made it – which is really important for me, because I don’t like to be attached to materiality too much.

Would you say that it is the process of creating something that motivates you to produce new work?

It’s very dualistic in that sense. I think the reason I started in fashion and making things was really because I am very inspired by materials – experimenting with them and creating the metamorphosis in my own hands. For me, it is about the process and that magical moment of transforming something into something else, and the devotion of time in that. But at the same time, I’m not attached to materiality in the later stages. When something is finished, I can really enjoy seeing it or using it, but I’m not really attached. Maybe I’m just mostly fascinated about things that are transforming. So, materials that have the potential of something else.