The American architect Louis Kahn (1907-1974) is often described as ‘the architect’s architect’. This was how he was introduced to an audience gathered at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) yesterday evening for a special screening of the film My Architect, a documentary made by Kahn’s son Nathaniel, first released in 2003. As the President of the RIBA Stephen Hodder told us in his introduction to the film, Kahn has gathered a devoted following inside the architecture profession. His public profile is now to be raised in the opening of a retrospective, currently showing at London’s Design Museum (9 July-12 Oct 2014).

The phrases ‘the architect’s architect’ or ‘the designer’s designer’ fascinate me. I came across both many times in my PhD research and in my research here at the V&A, where I think a lot about the relationship between design research and practice. These phrases, I think, specifically pertain to those professions which hang somewhere in the space between an art and a profession. What interests me about Louis Kahn is therefore not so much the buildings he designed (there are plenty of others researching those), but the qualities that make him valued and appreciated by his peers. Why should an architect be so celebrated inside the profession and relatively unknown outside of it? What does he represent to other architects that the general public did not see?

Film presents a wonderful opportunity to study the stereotypes, ideals and popular tropes that are used to represent professions of all kinds, but I’m always interested to see how it represents those who work creatively. A whole host of seemingly trivial questions fascinate me about how architects and designers are represented in film and in other media, such as:

What is it about the language, style and representation of architects that inspires such heroism?

Why do they all wear Corbusier-style glasses?

And, notably: Where are the women??

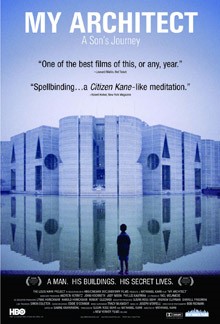

There is plenty of material in My Architect to give thought to these questions and more. Kahn’s son, Nathaniel, did an amazing job gathering together archive footage from the Kahn archive at the University of Pennsylvania and interviews with the architects and others who worked with him. Rather than an epic homage to architect-as-hero, My Architect is a moving and sensitive portrayal of someone trying understand his father- it is, as the subtitle to the film states, ‘A Son’s Journey’.

Trailer for My Architect (2003).

For this reason, the film brought into sharp focus the distinction between the categories ‘My Architect’ and the ‘Architect’s Architect’. While the former refers to Nathaniel’s personal quest to understand his father, the latter refers to Kahn’s celebrated reputation within profession. The two are explored and judged on very different terms. Nathaniel, not himself an architect, was interested in finding out what kind of person Kahn was, what moved him, what caused him to travel the world, what motivated him and how did he feel? By contrast. the architects he interviews along the way (including Frank O Gehry, Philip Johnson and Balkrishna Doshi) were interested in Kahn for very different reasons. They praised and admired his disregard for money, his privacy, his unsentimentality for family life, his contempt for ‘the client’, his absolute unwavering dedication to ‘the art’ of architecture and his uncompromising, steely determination to execute his plans exactly as he wanted them. (Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead sprung to mind quite a few times when I was watching the film).

One of the key roles of a public museum or gallery is, it seems to me, to introduce the brilliant ideas that are often contained inside creative professions to a wider audience. Retrospective exhibitions should ideally find a perspective somewhere between ‘my architect’ and the ‘architect’s architect’. However, this often poses challenges for curators and researchers, since we are often on the ‘inside’ too. It will be fascinating to see how the Design Museum has dealt with this in the exhibition.