We’d finally made it: the very last Object Pitches for a history of an OBJECT in 100 worlds. Befitting the occasion Bill Sherman was in a ruminative mood, reminding us that “the only rule is time.”

And so we settled ourselves for the last lunchtime session, which included yet another member of the Research Department making a case for an object that isn’t actually in the V&A – what is it about researchers and their inability to follow simple guidelines? – as well as a presentation that was introduced with the call: “Let’s Rock N’ Roll!”. In other hands this might have been hubris, in Ken Pegg’s case it was nothing but the truth.

For the last time, it was over to Bill and his stopwatch in this first of two blog posts about Object Pitch Day 8…

OP8/01

First up was Cathy Haill, Curator in the Theatre & Performance Department, who had brought her object along and, drummed up excitement with the comment, “He likes theatrical lighting.” When the moment for unveiling finally came, Cathy adopted a suitably theatrical tenor to declare: “Ladies and Gentlemen! Let me introduce Old Red Nose himself – Mr Punch – no stranger to a public forum since he has been performing in Great Britain for over 350 years.”

(The specific Mr Punch Cathy showed us (Museum no. S.373-2015) is a very new acquisition and hasn’t been photographed yet. One of his fellow Punches kindly agreed to step in and have his picture featured in this post instead.)

Cathy told us that a 2006 government initiative to create a list of British icons saw “Mr Punch and the current Mrs Punch in the top 12, alongside fish and chips, double-decker buses, Sherlock Holmes and the bowler hat.” Framing her choice as a conundrum, Mr Punch being “an archetypical British figure, descended from an Italian immigrant and with relatives all over Europe,” Cathy sketched his family tree, citing variants on the character found in France, Italy, Germany, Turkey, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Delving into Mr Punch’s cultural history, Cathy revealed how his “roots spread wide to encompass ancient Greek farce, the universal trickster of world folklore, the figure of ‘Vice’ in medieval mystery plays, the court jester, Mister Merriman and Shakespeare’s wise fool.”

By tracing Punch’s intricate history from the 17th century, she also demonstrated the fluid meanings generated by this character, as well as his impressive endurance.

Punch’s first recorded visit to London was in the company of one Signor Bologna, with the diarist Samuel Pepys’s entry for 9 May 1662 recording a performance in Covent Garden and, “… an Italian puppet play that is within the rayles there, which is very pretty, the best that ever I saw, and a great resort of gallants.”

Pepys’s name for the puppet – ‘Polichinello’ – revealed yet another of Punch’s close kin, Pulchinello – a character we previously encountered during Donatella Barbieri’s presentation on Object Pitch Day 3 – the “subversive thuggish lout” from the Commedia dell’Arte, who “got his name from the word ‘pulchino’ – or ‘chicken’ – and recognisable from his beak-like nose and squeaky voice.”

By the early 18th century, Punch was “the leading character in Martin Powell’s marionette theatre in Bath, where he danced in Noah’s Ark with his first wife, the shrewish Dame Joan”. In 1710, he was “back in London performing in St Martin’s Lane, appearing in variety of satirical plays for adults.” By 1738, he was starry enough to have a “theatre in London named after him, Punch’s Theatre in Haymarket, where satirical marionette plays were performed with Punch as leading man.”

Such was Punch’s popularity, that his absence from a performance even caused a riot in 1773. Cathy cited an account in ‘The Morning Chronicle’, an 18th-century newspaper, where “…from the illiberal, unmanly conduct of the gallery, it seemed as if some of the persons had come to the theatre, not in hopes of seeing a primitive but a modern puppet-shew, and that they grew out of temper because Punch, his wife Joan, and Little Ben the Sailor, did not make an appearance.” The play was subsequently revised to include a human Punch.

By the end of the 18th century, “Punch had cut the strings”, with “Italian showmen presenting glove puppet versions in small portable booths”.

Even Bigger changes were to come in the 19th century, including the loss of Joan in 1818 and her replacement by a new girlfriend, Polly, alongside “a move from adult satire to domestic, action-packed slapstick drama, taking the devil and hangman of medieval English drama with him, and describing Punch’s enduring problems with childcare and a nagging wife.”

Broader historic developments, including railways, leisure, tourism, development of Victorian coastal resort, eventually took Punch to the place he’s probably best associated with: the seaside.

Cathy concluded her account of this “survivor, who outlived all his fellow anarchistic merry men” by showing how he persists in literature, film (including Punch and Judy Man with Tony Hancock), opera (Harrison Birtwistle’s sinister 1968 production, Punch and Judy) and art (as in Susan Hillier’s 1990 installation at Tate, ‘An Entertainment’).

There was, of course, only one way she could finish a pitch for this most enduring of theatrical performers: “That’s the way to do it!”

OP8/02

Next up was Dawn Hoskin, Assistant Curator on the Europe 1600-1800 Galleries, whose pitch recalled both Rory Hyde’s aeronautic saucer from Day 5 and Avalon Fotheringham’s bandana from Day 6. (By this point in the process, we were lean, mean and totally able to make connections across object pitches.)

Her object was “a striking handkerchief produced in Alsace to commemorate the first ascent of a manned, hydrogen-filled, balloon on 1st December 1783” and, as such, was “an example of ballooning merchandise produced at the peak of the ‘balloonmania’ in France.”

Dawn started by looking closely at her object, explaining that it had been “acquired by the V&A as part of a large collection of textiles purchased from Dr Robert Forrer, a Swiss-born archaeologist and antiques dealer”. Beyond the “small ‘B’ embroidered in the corner”, we have no details of its previous owners.

The handkerchief is itself “a cotton square, plain-weave, block-printed in red, yellow, brown and black, and pencilled with indigo dye”; its “two vertical edges have been left as raw selvages, with the horizontal edges tightly hemmed.” Its border “is composed of a symmetrical pattern showing the Tuileries Palace in Paris in the background”, with the centre dominated by a balloon and its gondola basket containing two men.

In explaining the potency of this imagery for the handkerchief’s contemporaries, Dawn explained that “the development of balloon flight was a scientific feat that truly caught popular imagination”, with feats including the Montgolfier brothers’ “first public demonstration of their ‘hot-air’ balloon on 4 June 1783.” Although early innovations in ballooning occurred exclusively in France, “reports of ballooning successes later inspired a host of imitators and innovators to take to the air in other areas of Europe.”

Dawn’s object actually commemorated one very specific episode from the history of ballooning: “the first manned, hydrogen-filled, balloon that ascended from the Tuileries Palace in Paris on 1 December 1783”; an event that came just ten days after the Montgolfiers made their first untethered fight, and “lasted over two hours, with the hydrogen-filled balloon finally landing 12 kilometres south of Boulogne.”

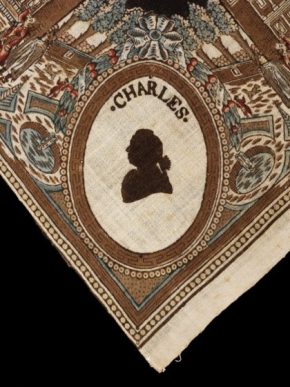

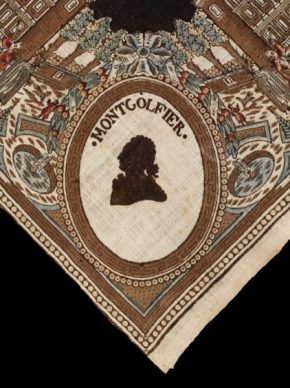

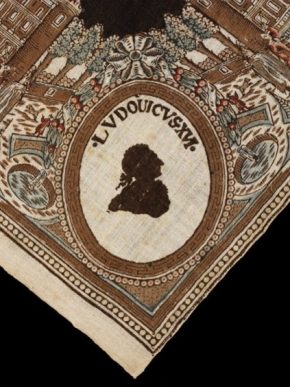

Returning to the images on her object, Dawn delved into the worlds of men shown in the silhouette cameos decorating the handkerchief, as well as the prestige associated with ballooning.

Illustrated were: “the lecturer and physicist Jacques-Alexandre-César Charles, who oversaw the project and was the designer and pilot of the balloon”

“Nicolas-Louis Robert and his brother Anne-Jean, both manufacturers of physics instruments, who worked with Charles to construct the balloon”…

“The silhouette named as Montgolfier is probably intended to represent Joseph Montgolfier, honoured by an invitation to release the pilot balloon before the flight”…

…and Louis XVI, the French king, who showed royal favour for the project and gave permission for the ascent to be made from the Tuileries, one of his royal palaces in Paris.

Stepping back from the specific figures shown, the handkerchief, like Rory’s saucer, also attests to “the history of man’s longing for and development of flight. From the wonder of floating, transient bubbles, to the vast variety of aircraft today.”

To press the point, Dawn quoted Baron von Grimm, journalist, diplomat and contributor to the Encyclopédie, one of 18th-century Europe’s major intellectual achievements, who stated:

“Never has a soap bubble held the attention of a group of children in the way that the air-balloon has been, for a month now, holding the attention of the town and the court. … all one hears is talk of experiments, atmospheric air, inflammable gas, flying cars, journeys in the sky.”

Von Grimm’s poetic evocation shows the ways in which balloon flight “ignited peoples’ imaginations”, leading us to the worlds of art, literature, poetry, philosophy and the natural sciences.

This takes us from notions of the sublime, as found in works by Coleridge, Wordsworth and Shelley, to “new achievements in the world of sciences, such as enhanced understanding of hydrogen (‘inflammable air’), physics and air pressure”, to the “worlds of the print-makers and publishers who disseminated depictions of balloon flights” – some of which informed the images on the handkerchief.

Dawn then traced the impact of ballooning across Europe, through “a deluge of consumer items” in the form of “numerous objects decorated with ballooning iconography, as people of varying social positions looked to demonstrate their fascination, engagement with or admiration of balloon flight.”

The figure of the balloon, still instantly recognisable today, can be found on “fans, low- and high-end ceramics, glass beadwork, furniture, printed textiles and domestically-produced items such as samplers.”

Ballooning even influenced fashionable clothing in the form of “puffed sleeves on dresses, large hats, coiffures and waistcoat designs, which were all adapted to become ‘au ballon’.”

The “increasingly imaginative world of commercial exploitation of imagery” also shaped depictions of those involved in the flight, “taking us to the world of ‘creating celebrities’, as these early airmen became new icons”, and showing “how achievements in the world of science extended to encompass the worlds of showmanship and show business.”

Like all fast fashions, fads and crazes, ‘balloonmania’s’ stratospheric rise was countered by a fall. The zenith of ballooning’s popularity, “immediately following the early achievements of balloonists during 1783”, didn’t last. Before long, ‘balloonmania’ had become “a prime target for satire and caricature”, offering another theme to explore.

Commentators including the writer Samuel Johnson and the botanist and naturalist Sir Joseph Banks criticised the usefulness of ballooning experiments, with Johnson remarking, “I had rather now find a medicine that can ease an asthma.”

Recalling Avalon’s presentation, Dawn dwelt on the materiality of her object and the worlds it opened up by means of “production methods, the manufacturer and workers, and finally sale and use.” Notably, the 18th-century version of the handkerchief was far more versatile than the one we’re familiar with, being “used as a bag, a nightcap, an accessory, a medical dressing, a substitute for rope, or a rag – a world of multiplicities!”

Dawn finished her pitch in “the ‘world’ of the textile conservation studio, where the handkerchief is currently being restored and mounted on to a padded board for display in the world of a permanent display in the Europe 1600-1800 Galleries.” We can’t wait!

OP8/03

Our next pitcher was Angela McShane, Senior Tutor for the V&A/RCA History of Design MA, and the V&A’s resident early modern historian. Once again, the Research Department proved to be a hotbed of rebellion, as Angela, like Guy Julier, chose an object that isn’t actually in the museum’s collection.

As her presentation was so fabulous, we let her off the hook and let her make a case for this large pewter tankard, now in the collection of Holy Trinity Church, Rolleston, Nottinghamshire.

She introduced her pitch by explaining that her object and its “interactive use and decoration, encompassed whole series of worlds – heaven, hearts and souls – as well as a large tranche of the earthly globe.”

Like all good historians, Angela set up the terms of her argument, clarifying what an object from Rolleston in Nottingham has to do the V&A. The tankard, “brought by its current owners to the V&A to seek advice”, offers a “way of understand the social function of two typical V&A categories of objects”, which she illustrated with two vessels “made of other metals (glass was understood as metal in 17th century) that we currently distinguish as secular and sacred.”

Her presentation interrogated and complicated these categories, “tracing the journey from secular to sacred, and through some ambiguous space in between.”

Beginning with what the tankard once contained, Angela corrected the assumption that pewter and tankards were always associated with beer drinking, explaining that “this tankard was carefully constructed by its maker to contain four early modern wine pints – beer pints were larger.”

Its contents and function provide vitals clues about the worlds it once inhabited: from “the international world of the wine trade, centred on southern and central Europe”, to the world of conviviality and company, where “it was intended for sharing and creating bonds between friends and strangers – a whole world of people.”

Angela interpreted her object’s decoration within the political world of the late 17th century, explaining that its iconography was deliberately designed to “test drinkers’ bonds of allegiance.”

To do this, the tankard was “covered in loyal dynastic iconography that seems to celebrate the marriage of Charles II and his Portuguese wife Catherine of Braganza”, an event that took place in 1662. Angela built on this notion to demonstrate how politics might be embedded in the design of an early modern object, situating the tankard as something that “required the heart to be as engaged as the head – and which, in fact, actually sought to bypass the dangerous head, and thereby ensure the loyalty of the heart through consumption of alcohol.”

In fact, although this is the only surviving tankard with precisely this decorative scheme, it was one of “a range of goods showing the Restored Charles II and his wife, which also included embroidery, silver lockets, ceramics and prints.”

In common with other lidded objects, the tankard must also be located in a world of honour, as it “participated in an important gestural world of hat honour before it could be used.” The “placing of Catherine of Braganza alone on its lid – a crucial sign of respect – demonstrated her importance to its inspiration.”

Angela then showed how her object was shaped by a mix of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art influences, offering evidence for how art and design motifs were tweaked and translated across media.

As an example of wriggle-work, it reveals the world of the early modern artisan, while the portrayal of Catherine of Braganza in the guise of a shepherdess reflects her presentation in portraits “painted in the early 1660s shortly after arrival in England.”

Notably, there are no sheep in the wriggle-worked portrait; instead Catherine is shown with the easier-to-depict symbol of the crook, indicating just how much “materiality shaped representational iconography.” As Angela clarified, these images came “not so much from portrait painters but from similar motifs used by embroiderers, bringing the pewter tankard into the world of textiles.”

By looking even closer at her object, Angela challenged the assumption that the tankard commemorated the royal wedding in 1662, offering a far more complicated – and compelling – reading of its politicised iconography.

Two marks belonging to two different men are present on the tankard: “one for John Parkinson, a specialist flagon-maker, the other for Robert Hannon, who probably sold the tankard from his shop or arranged its commission.” Significantly, “both men were only active after 1683 – 20 years after the wedding in 1662 – showing how the tankard was not so much a commemorative piece as an ideological statement.”

What more can we make of this? As Angela elaborated, this object “was almost certainly used to facilitate drinking rituals that marked the beginnings of party politics in England from 1679 onwards” and, as such, fits into the fluid, constantly changing political scene of the late 17th century – an observation that feels particularly topical this week before the General Election and the challenges to the two-party system happening right now.

Explaining why her object was most probably a “Tory statement”, she revealed the very specific political events that shaped its form and use. The prominence of Charles II and Catherine of Braganza in its design was intended to “emphasise the continuity of the royal couple in marriage, as well as the queen’s central position.” In combination, these elements were in reaction to the Exclusion Crisis and “Whig attempts to exclude the King’s Catholic brother James, Duke of York, from the succession and encourage Charles II to divorce his barren wife, Catherine, to provide the country with a Protestant heir.” These events “culminated in a plot against the Duke and King’s life in 1683, popularly known as the Rye House Plot.”

These overlapping issues of design, ritual and politics mean “we think the tankard was commissioned as a loyal statement by a Tory for quasi-sacral ritual drinking events that accompanied the King’s deliberately lavish celebration of Catherine’s birthday in 1684.”

Angela finished her pitch in the 18th century, where “the tankard became part of similar if more orderly drinking rituals in church after being given by an unknown donor to the parish church of Rolleston, Nottinghamshire.” Here, it made “a new ideological, if somewhat ambiguous, statement, linking loyalty to the state and the established church.”

***

With so much packed into the first half hour – and so many words and worlds already in this post – let’s pause for breath.

In just three pitches, we had already touched on issues including popular culture, the surprising origins of national icons, religious practice and the place of designed things in political discussions, and followed key literary and visual motifs (lords of misrule, shepherdesses, balloons) across media, commodities, price points and markets.

It was with heavy hearts that we settled ourselves again for what would be the very last pitches in this round of a history of an OBJECT in 100 worlds…