by EVE ZAUNBRECHER

The popularity of reality TV shows such as Hoarders and Hoarding: Buried Alive have introduced hoarding into popular culture and have raised interesting debates about rampant consumerism and the politics of mental health disorders. Hoarders, once dismissed as ‘pack rats’ or ‘messies’, have now been located on the Obsessive Compulsive Disorder spectrum as an established pathology. Dr. Fabio Gygi, a lecturer in Anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies, spoke at the V&A/RCA History of Design Research Seminar about hoarding in Japan and the differences in attitudes towards collecting, accumulating, and hoarding from the Victorian period to the present.

Dr. Gygi focused on his fieldwork in Tokyo, assisting hoarders with decluttering their homes in an anthropological study of their accumulation habits. Hoarding would seem to contradict the stereotypical minimalist Japanese interior, but rampant consumption exists just as much in Japan as in Western countries. For example, Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s book Happy Victims explores the collections of several Tokyo collectors whose small flats are overflowing with items from particular designer clothing brands. The collectors feel both joy and anxiety as their collections of brands like Anna Sui and Comme des Garçons slowly overwhelm their living spaces. Dr. Gygi suggested that collecting differs from hoarding in that it is goal-driven; a collector seeks to find all items of a particular set which can have a finite end, but hoarders accumulate without a specific goal in mind. Their behaviour is an extension of the seemingly ordinary practices of decorating interiors that began in the nineteenth century, well after mass production and consumer culture emerged.

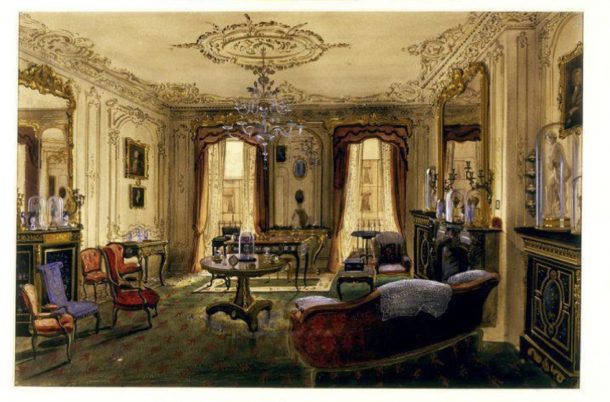

Dr. Gygi proposed that the changing role of possessions in the home and interior design since the Victorian era has altered previous attitudes towards our relationships with things and towards quantity, accumulation, and collecting. Domestic interiors during the Victorian period became a space to display the identity of the owner through carefully curated collections of objects. No space was left blank, including walls, floors, shelves, and tables. Upholstered furniture and heavy window hangings satisfied the obsessive need to cover things with things, and provided, for men in particular, a soft insulation from the hectic world of work. A tightly compacted collection of fashionable objects in a room would communicate the owner’s taste and financial freedom to consume, and a ‘cluttered’ home suggested life inside. Decorating interiors became a ‘process of inhabitation’, animating the lifeless household with the material evidence of its occupants.

The ‘compulsion’ to cover interior spaces has intensified and continued to the present day in Japan in the homes of hoarders. Dr. Gygi argued that hoarders can create their own archaeology within layers of items; in cleaning one hoarder’s home, he was able to date parts of the hoard by the discarded newspapers and dated technology. This physical representation of the hoarder’s life can help stabilize their identity as time moves forward; if possessions can remain static, a hoarder can remain the same as well. Possessions can insulate a hoarder from the world outside their walls and either intentionally or subconsciously prevent socializing. Things, just as they did for the Victorians, protect and insulate hoarders in a space that physically mirrors the mind.

Dr. Gygi also spoke about the medicalization of hoarding, which is now an established pathology within the Obsessive Compulsive Disorder spectrum. Dr. Gygi suggested that classifying this disorder on the OCD spectrum is more for legal than medical reasons, since many hoarders can only avoid eviction if they seek medical treatment for hoarding behavior. Unlike any other disorder on the OCD spectrum, a diagnosis for hoarding can only occur when there are possessions in the home. The number of items in a home and what physical dangers they pose come into consideration when diagnosing this disorder, but the idea of consumption is not the enemy here. Rather, hoarders must learn when that arbitrary line has been crossed, when many possessions become ‘too many’.

Dr. Gygi’s research raises interesting questions about how we perceive hoarding behaviours. The difference between passionate collecting and a serious mental disorder may not be as clear as reality shows would have us think. Hoarding has as many social factors as medical ones; for instance, would we ever consider a museum collection a hoard? The V&A has long had the reputation of being the ‘nation’s attic,’ but the museum’s objects have so much monetary and cultural value that accumulation is encouraged. A museum may differ from a personal collection in that it is highly documented, organized, and purpose-driven, but hoarders can have just as much purpose in mind for their collection of items. As Dr. Gygi explained, categorizing hoarding as a mental disorder can help hoarders avoid eviction or health hazards, but this diagnosis does not always acknowledge the human need to insulate our homes with things. We fill our homes with objects that delight our senses and ‘protect’ us, and just as the Victorians believed that a cluttered home showed signs of life, our possessions make the cold surfaces of our houses seem more human.