One of the fascinating things about design drawings, at least to me, is that you often can’t tell whether they are for presentation, for working out a design concept, or just recording an object once it’s finished. Sometimes, perhaps, there is a bit of all three going on. The confusion really sets in when you see aesthetic touches on what you would otherwise expect to be a ‘working sketch.’ For whose benefit has the drawing been prettied up? Maybe the draftsman was taking pride in the work. Maybe there was an internal politics in play, where the designer wants the boss, or even the executor of the object, to take the job seriously. Maybe the drawing would be shown to a private client or retailer, as well as being used internally. As I said, it’s confusing.

These thoughts were prompted recently by a group of drawings for silver that are held within the Edward Barnard & Sons archive. Most of the archive was recently donated to the V&A’s Archive of Art and Design by Barnards’ parent company, Padgett and Braham. It’s an extraordinary body of material, recording the firm’s work in detail throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – although it traces its origins back to c.1680. (Incidentally, you can see other design drawings for metalwork in the Silver Galleries at the V&A).

In addition, the archive includes business ledgers, glass negative photos, pattern books (including some 19th and even 18th century ones that the company collected for design inspiration), and lots and lots of parts that could be used for casting. The drawers full of handles, spouts, and other bits and pieces of teapots, sugar bowls and who knows what else are like a Deconstructivist’s junk shop.

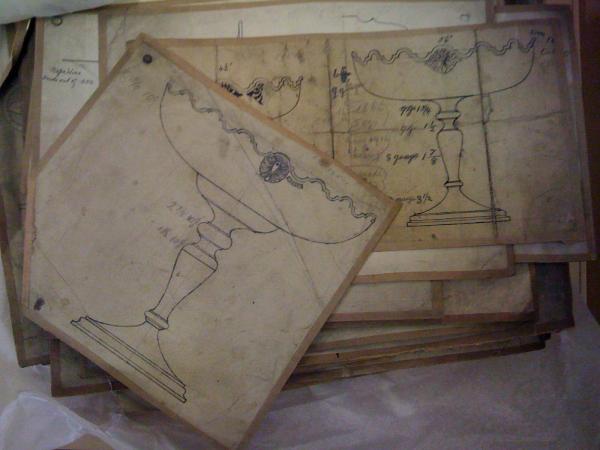

Most of the drawings in the Barnard archive seem to be quite utilitarian. They capture profiles, and sometimes show multiple sizes of a single design layered on one sheet.

The shop used its drawings to capture lots of information, including dates (sometimes more than one, presumably each time the piece had gone into production), dimensions, the names of clients, and also symbols that linked the drawing to boxes of patterns.

When going through such a large body of apparently workaday material, it was a real surprise to find a few drawings of a more artistic nature. They aren’t exactly still life paintings, but for some reason, the draftsmen at the firm sometimes went to the trouble of rendering the reflective surface of the metal objects. Here are a couple of examples: an art deco sweet dish from the 1930s, and a low tray, probably in silver-gilt.

In the dish on the left, in particular, the draftsman even added a touch of blue to give a convincing effect of silver. More research about the Barnard archive is definitely called for (the museum needs to get the huge body of material organized first), but I think these drawings were doing double-duty. They suggest direct communication with a prospective client, whom Barnard & Sons were probably trying to impress with a shiny surface, but also were used in-house to work up and/or record the design.

One last fascinating drawing from the archive dates to the shop’s final year. In this case we know the date precisely, because what was kept was not the original but a fax, sent on 13 November, 1990.  This must have been one of the very last objects made by the firm, and it shows that Barnard & Sons had turned to ‘outsourcing.’ It was sent by the firm to a certain Bernie, who would ‘spin’ the main elements of the vase – that is, form sheet metal over a wooden profile using a lathe. (See this video for footage of this process in action.) The drawing is wonderfully specific about the making process, noting that the spun elements would be joined together with a cast knop between the foot and the body, and that ‘fancy wire’ would be added near the rim.

This must have been one of the very last objects made by the firm, and it shows that Barnard & Sons had turned to ‘outsourcing.’ It was sent by the firm to a certain Bernie, who would ‘spin’ the main elements of the vase – that is, form sheet metal over a wooden profile using a lathe. (See this video for footage of this process in action.) The drawing is wonderfully specific about the making process, noting that the spun elements would be joined together with a cast knop between the foot and the body, and that ‘fancy wire’ would be added near the rim.

Of course smiths have relied on ‘outsourcing’ for centuries – making silver, like many other traditional crafts, was a specialized trade that lent itself well to the division of labor long before factory production was the norm. But this fax still seems eloquent to me of the decline of the silver industry. By 1990, Barnard & Sons had gone from being one of London’s leading decorative art manufacturers to a very small operation. In general, the twentieth century wasn’t kind to silversmiths. Their key sales items were formal dining and commemorative pieces, both of which went way out of fashion after World War II and haven’t come back in since. Most craftspeople still working in the medium are either ‘studio artists,’ working alone and often employed in teaching; or reproduction makers who don’t do much in the way of new designs. That so much expertise and history went by the wayside so recently is a bit heartbreaking. But thanks to the preservation of this archive, we can at least get some sense of this firm, and how it went about bringing a bit of a shine to the British home for almost two centuries.