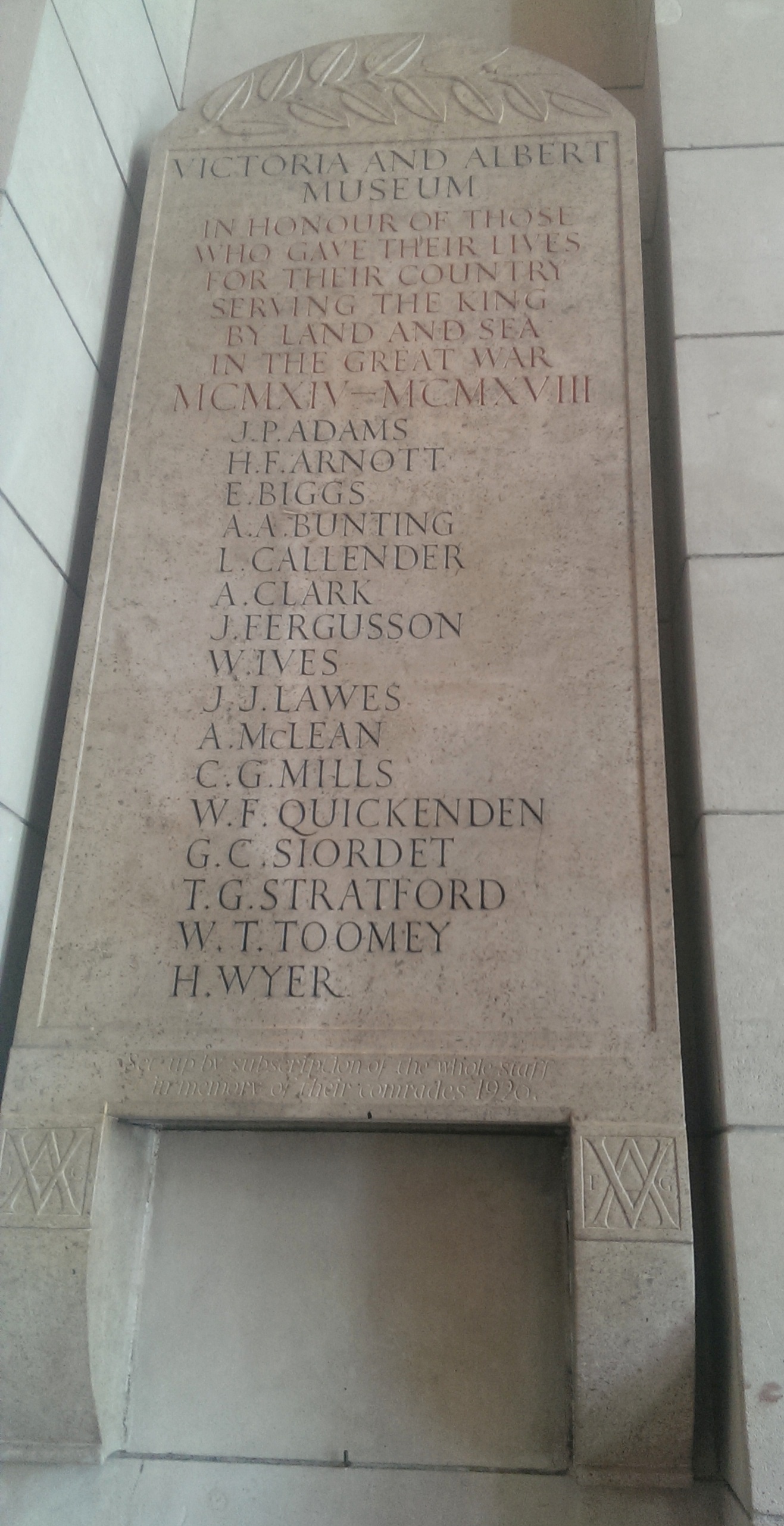

Simple and solemn in cream Hopton Wood stone, the V&A’s monument to its 1914-18 war dead sits unobtrusively in the main entrance hall. Designed in 1919 by the sculptor and typographer Eric Gill, it was commissioned by the Museum with the dual aims of commemorating the fallen and acquiring an example of Gill lettering. As such, funds were made available from the Museum’s acquisition budget – in the end, however, the cost was covered by a voluntary subscription among the Museum’s staff. Its unveiling in April 1920 attracted a good deal of press coverage, and it is now formally catalogued as part of the Sculpture collection.

Simple and solemn in cream Hopton Wood stone, the V&A’s monument to its 1914-18 war dead sits unobtrusively in the main entrance hall. Designed in 1919 by the sculptor and typographer Eric Gill, it was commissioned by the Museum with the dual aims of commemorating the fallen and acquiring an example of Gill lettering. As such, funds were made available from the Museum’s acquisition budget – in the end, however, the cost was covered by a voluntary subscription among the Museum’s staff. Its unveiling in April 1920 attracted a good deal of press coverage, and it is now formally catalogued as part of the Sculpture collection.

It’s tempting to view this stone as an archive in its own right, as well as a sculpture object. It comprises a simple list of initials and surnames, bearing testament to the fallen. The decision to keep the inscription simple was a deliberate one: in a letter dated 21 August 1919, Sir Eric Maclagan (then Keeper of the Department of Architecture and Sculpture) wrote “Naturally from the point of view of personal interest these [details] are of value; from the point of view of the inscription they would be better away.”

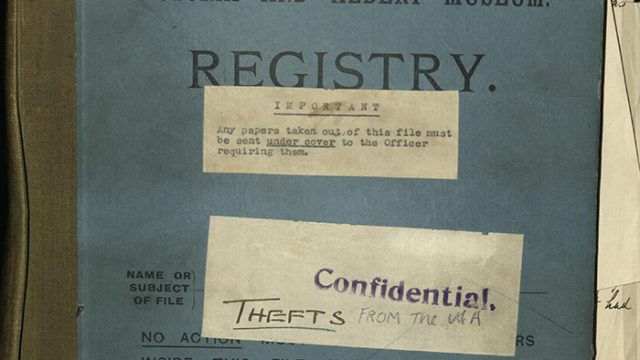

Perhaps, then, a fitting way for us to commemorate the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War would be to look more closely at the names on the stone, and tell their stories as far as is possible. By looking at old staff lists for the years leading up to 1914, it’s been possible to establish at least some basic details for most of the men listed here, such as occupation and rate of pay. The 1911 Census was also helpful. Once this data had been used to establish first names and dates of birth, it was then possible to cross-reference these with the registers of war dead maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The CWGC provided further information on the men’s next of kin, their place of burial and – importantly – the Army unit or Naval vessel to which they had been assigned; and it’s this latter detail which sometimes enables a reconstruction of a man’s likely postings and movements.

You might think, given the Army’s penchant for record-keeping in triplicate, that such an elaborate combing of the archives would be unnecessary! To the misfortune of military and family historians, however, the vast majority of First World War personnel records were destroyed by bombing during the Second World War. So we make do with the information we have. And so, to the greatest extent possible, these are the details of those sixteen men who were lost:

John Philip Adams (b.1885), rank and regiment not known. Assistant Clerk on £65 pa. Date of death (DOD) not known

Gunner Hugh Fowler Arnott (1882-1917), Royal Garrison Artillery (112th Heavy Battery). Cleaner on £65 pa. Son of Hugh Irving Arnott. DOD 19/10/1917

E. Biggs, could not be traced

Rifleman Alfred Arthur Bunting (1881-1917), London Regiment (City of London Rifles). Carpenter on £110 6s 9d pa. Husband of Elizabeth Bunting. Lived at 97 Stormont Road, Clapham. DOD 14/7/1917

Corporal Leonard Callender (1887-1916), Royal Field Artillery (5th Division Ammunition Column). Warder-Cleaner on £72 16s pa. DOD 10/9/1916

Serjeant Alfred Clark (1872-1916), Military Police Corps. Warder-Cleaner on £72 16s pa. Son of Mr. and Mrs. Clark, of Clewer, Windsor; husband of A. L. Clark. Lived at 35 Maxwell Rd., Fulham.DOD 15/1/1916

Private James Fergusson (1884-1914), The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. Warder-Cleaner on £72 16s pa. DOD 14/9/14

William Ives (b.1882), rank and regiment not known. Cleaner on £65 pa. DOD not known

Private James John Lawes (1872-1915), Royal Marine Light Infantry (Chatham Battalion). Warder-Cleaner on £78 pa. Husband of Mary L. Lawes. Lived at 25 Lorne Gardens, Notting Hill. DOD 30/4/15

A. McLean, could not be traced

C. G. Mills, could not be traced

Serjeant William Frederick Quickenden (1895-1918), London Regiment (London Irish Rifles), 18th Battalion. Boy Messenger in Architecture & Sculpture Dept. on £31 4s pa. Son of Mr R. & Mrs A. Quickenden, of 50 Archel Road, West Kensington. DOD 23/3/1918

2nd Lieutenant Gerald Caldwell Siordet M.C. (1885-1917), Rifle Brigade 13th Battalion. Temporary Cataloguer in Architecture & Sculpture Dept. Son of George Crosbie Siordet & Marie Beatrice Siordet. DOD 9/2/1917

Yeoman of Signals 2nd Class Thomas George Stratford (1873-1914), H.M.S. Hogue. Art Workroom Repairer on £114 8s. DOD 22/09/1914

Corporal William Thomas Toomey (1887-1918), Leinster Regiment, 2nd Battalion. Attendant 2nd Class on £62 pa. Son of James and Janet Frances Toomey; husband of Elizabeth F. Toomey. Lived at 85 Guinness Buildings, Lever Street, City Road. DOD 26/1/1918

Lance Serjeant Herbert Wyer (1883-1914), Coldstream Guards, 3rd Battalion. Warder-Cleaner on £72 16s pa. Son of Mr and Mrs John Wyer, of Watton, Norfolk; husband of Annie Louisa Wyer. Lived at 217 Wandsworth Bridge Road, Fulham. DOD 2/11/1914

Sixteen names with sixteen stories. Some yielded more information than others but, taken as a group, it’s possible to fit these men into the broader narrative of military recruitment, volunteering and conscription that affected over five million British men during the First World War. Judging by the dates of death, for example, at least some of these men had to have been volunteers rather than conscripts, for conscription was not enacted until 1916. Some must have been reservists mobilised when the first crisis occurred in 1914. Callender, Clark, Fergusson, Lawes and Wyer (who seems to have been killed at the First Battle of Ypres) had all seen previous service, meaning they were likely to still be listed as reservists in 1914. Alfred Clark is perhaps the most notable example, granted medals for long service and good conduct having served with the King’s Dragoon Guards during the Second Boer War (1899-1902).

If these men are typical – and I think they are, being a mixture of clerks, skilled artisans, and less well-paid warders and cleaners – then their details belie the myth that the British Army was composed of significant numbers of boys; for most of our sixteen died between their late twenties and mid-thirties. The youngest, Quickenden, was 19 when war broke out and died aged 22, killed on a day in which his unit was defending the line against the onslaught of the German ‘Spring Offensive’. The oldest, Clark, was 43 when he died.

Also typical is the predominance of the Army over the other branches of the armed forces. The only known exceptions to this are Lawes, who rejoined the Royal Marines, and Stratford, who served in the Navy aboard H.M.S. Hogue, and died when that ship was torpedoed by a German U-Boat in September 1914.

The ratio of commissioned officers to men and NCOs is reflected here: just one in this list of sixteen. The overall rate was roughly one in twenty, with about 250,000 commissions granted during the war and a total of five million men serving. That said, the proportion of junior officers killed-in-action outweighed the proportion of other ranks killed: 17% of captains, lieutenants and 2nd lieutenants were killed, compared with about 11% of all private soldiers and NCOs.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the class system of the time, that lone officer is the only man on the list to have definitely hailed from an upper-middle class background. 2nd Lieutentant Siordet’s family were bankers and insurance brokers, of Huguenot descent, and after graduating from Oxford he lived the life of a London bohemian, writing poetry and art criticism. He was friends with artists such as John Singer Sargent and – coincidentally – Gill himself. His relatively privileged background and education ensured that his life has been documented in greater detail than those of his contemporaries: we know, for example, that he enlisted as a private immediately after war was declared, but was swiftly commissioned as an officer. He was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry in 1916; and was killed in Basra during the Mesopotamian campaign.

The historical narrative of the First World War is well-known; the millions of individual men who fought in it are often forgotten to us. Recovering their identities is not only history in practice; it’s also a mark of thanks and respect.

Thursday 13th November will mark the 100th anniversary of the publication of the

following poem by Gerald Caldwell Siordet in ‘The Times’ newspaper:

Autumn 1914

O not in vain we have seen the royal decrease,

The splendid sinking of the slow-dying year;

O never again so dear to us, so dear

These golden days, these nights of starlit peace

When the moon rides in white cloud-companies.

O ye that have eyes to see, and ears to hear,

Who wait the call across the narrow seas,

God is not mocked, God mocks us not with these,

But, in the interior fastness of the heart,

That we may fail not to fulfil our part

Nor altogether lose Him when we fight

Nor, falling, altogether fall forlorn,

Hangs up remembered banners of the dawn,

And turns our faces inward to the light.

The poem was published under the name ‘Gerald Caldwell’ – possibly because the

name ‘Siordet’ did not sit well with the ‘anti-foreign’ feeling at that time.