Today we take it for granted that our museums and galleries offer their young visitors diverse and engaging learning activities and programmes designed to fire their creativity and imaginations. At the V&A, we want families to come and explore, enjoy and be inspired by our wonderful collections and spaces.

In the early twentieth century, however, museums could be daunting and unwelcoming places for children: The Times declared emphatically that ‘Nowhere else do children so soon begin to get tired at the knees and to think of meal-times’.

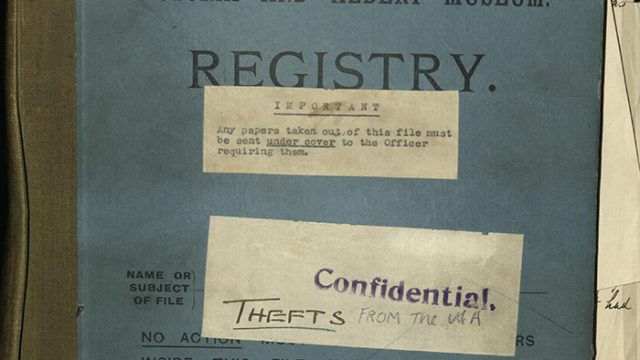

True to its pioneering spirit, however, in 1915 the V&A attempted an ‘interesting experiment’, as The Times described it (am I the only one to detect a note of equivocation behind that adjective ‘interesting’?). Documents in the V&A Archive tell the story.

In summer 1915, a shortage in the Fresh Air Fund’s finances meant that many city school children who might otherwise have gone to the country were left to their own devices during the school holidays. The more enterprising of them ventured through the V&A’s hallowed portals where ‘their attention was occupied mainly with dodging the policemen behind statues and showcases’. An opportunity presented itself. With the help of the energetic and redoubtable Ethel M. Spiller, a volunteer guide and secretary of the Art Teachers’ Guild, and other ladies, the V&A laid on ‘holiday instruction’ for its ‘more youthful visitors’, providing a ‘small room’ (baby steps!) in which children would be given ‘elementary instruction about objects in the Museum’.

The experiment’s success encouraged the V&A to adopt a more ambitious scheme for the Christmas holidays. From 26 December 1915 to 26 January 1916, Room 18 was set up as a dedicated ‘Children’s Room’; it was visited by 14,000 people (mostly children). Objects chosen specifically for their interest to boys and girls were displayed around the room.

The Daily Telegraph’s inventory of the exhibits betrays a child-like excitement:

‘For boys there are various objects dealing with, or connected with, war and fighting—for instance, rubbings of medieval brasses showing the armour of the period, casts of the models of Cromwellian soldiers in Cromwell House, Highgate, and objects illustrating the Napoleonic wars, including iron jewellery worn by the ladies of Prussia to replace the gold they had contributed to the war funds, and boxes, &c., made by French prisoners in England. For girls there are models of costumes of various periods and nationalities, and three dolls’ houses, including an English one of the eighteenth century and one of the late nineteenth century, completely furnished. There are also a set of Japanese dolls used in connection with the girls’ festival in Japan, graciously lent by her Royal Highness Princess Mary, and, in the adjoining gallery, a similar set used at the boys’ festival’.

How many of these objects can you spot in this photograph?

In addition, children were taken on tours of the galleries, their guides ‘selecting for discussion such works of art as are likely to interest, and stimulate the imagination of, children’. Also, practical demonstrations were arranged according to gender stereotypes (as we might understand them today): spinning, weaving and embroidery for the girls, stencilling and block printing for the boys.

Spiller eschewed a didactic approach. ‘We do not attempt to teach them’, she told The Times, ‘We point out interesting things in the Museum which they could not, perhaps, find for themselves. But we try to make them feel it is a holiday, and that we are not teachers, but ‘aunties’’.

Not all staff were quite so supportive of the Museum’s child-friendly initiatives. In 1925, one dashed off an intemperate memo to the Director to complain about the ‘troops of children congregating in the South Court … shouting, laughing, dragging chairs about, and swarming around the cases’. He warned that without appropriate supervision the galleries risked becoming ‘a mere children’s playground in holiday times’. Some of the warders were apparently too fearful of Miss Spiller’s authority to dare say anything!

Since ‘auntie’ Ethel Spiller’s pioneering experiment in 1915, the V&A’s provision for children has grown exponentially: from a single room in 1915 to an entire building (the Sackler Centre for Arts Education) in 2008. Today you can pick up a family trail or borrow a back-pack and venture into the galleries where there are also many hands-on interactives to find and play with. At the weekends, families can interact with a Pop-up Performance on Saturday or pick up a design challenge, hunt for ideas in the galleries, and then create fantastic designs with the Drop-in Design team on Sundays. During the school holidays, families can take part in Digital Kids and The Imagination Station or book onto a Make-it workshop.

Did you know that in 2012-2013 a staggering 469,700 children visited the Museum sites?!

For information about these activities check out the V&A Families webpage.