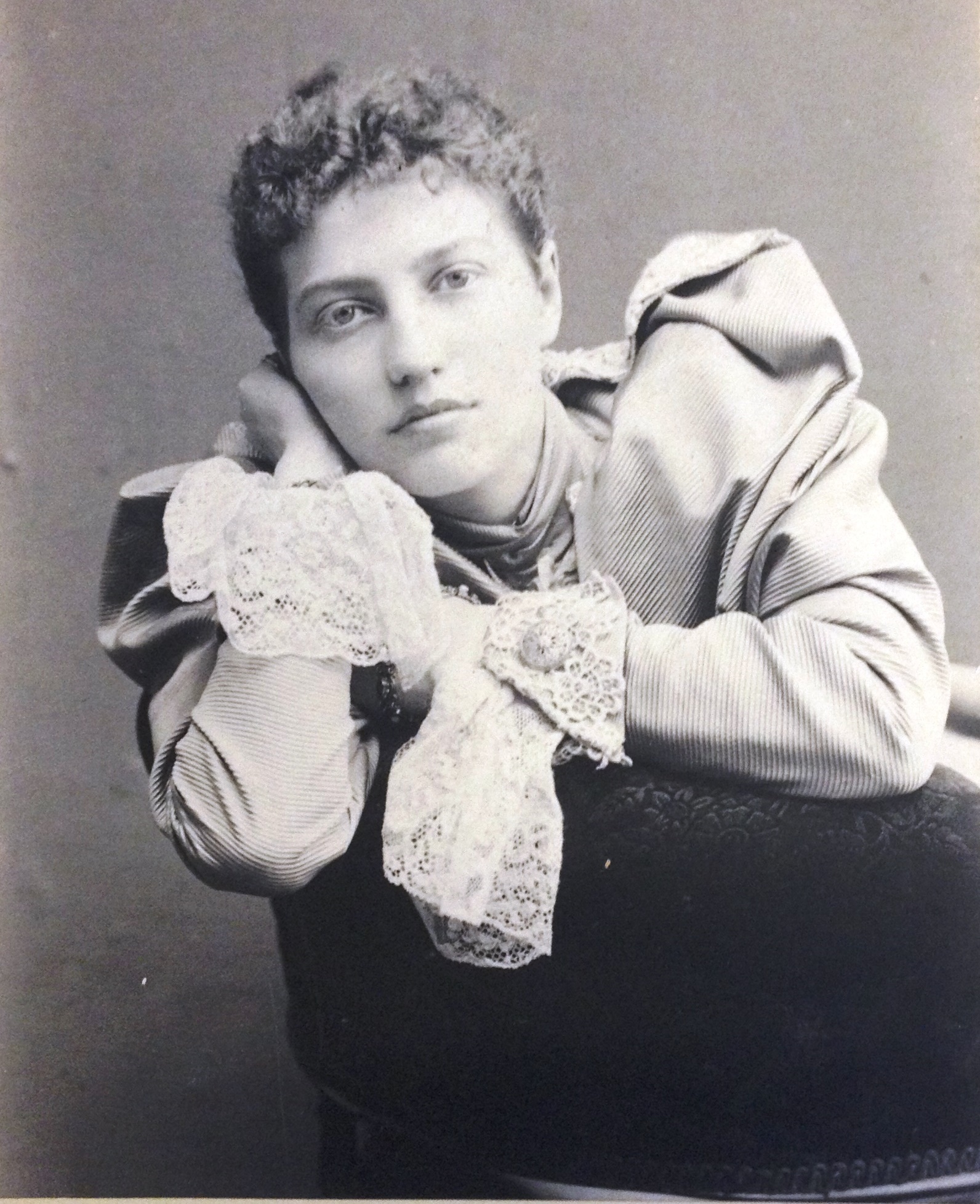

In February 1931, the sculptor Una Troubridge wrote an entry in her diary about a dinner party she had hosted that evening with her partner, the novelist Radclyffe Hall. Hall had been embroiled in controversy and notorious legal battles over her banned 1928 lesbian novel, ‘The Well of Loneliness’. Over drinks and dinner, Troubridge records that the conversation turned to a discussion about a woman named Gabrielle Enthoven – in terms that were far from complimentary. The couple called Enthoven a rat. They used to be friends with her, they said, but now they would have nothing more to do with her; indeed they had no further use for her. They said that she had disguised her sexuality and, in urging others to do the same, had betrayed them. To put it mildly, Enthoven was, in this period, deeply unpopular with the pair. This picture differs greatly from the one known of Enthoven as a well-regarded, if obsessive, collector and dedicated lover of the theatre who, seven years earlier in 1924, had donated her huge collection of theatrical memorabilia to the V&A.

Over the past couple of years, I have been looking through the collections at the Museum to discover more about the private and personal life of Enthoven. I’ve been looking into her friendships, her relationships, and the people she associated with. Her obsession with collecting theatrical material and her encyclopaedic knowledge of the theatre in London is fairly well documented. In an earlier blog post, Introducing Enthoven, Kate Dorney reveals how Enthoven’s impressive collection was formed and the cataloguing and indexing techniques she used to make her material accessible to researchers, students and theatre enthusiasts. I want to delve deeper into the life of the woman behind the collection. Who were her friends, or, indeed, her enemies? How can an understanding of a collector’s private life influence our understanding of their public collection? My research has taken me as far away as an archive in Austin, Texas. It was here in the Harry Ransom Center that I came across the diaries of Una Troubridge, with their cruel (albeit entertaining) snippets about her dislike of Enthoven. Although Enthoven is regularly described as being a generous and kind woman by other contemporaries who wrote about her, Troubridge’s opinion is obviously marred by Enthoven’s apparently public denial of her sexuality. Enthoven is often called a lesbian when she appears in various biographies of Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall. However, nothing I had previously read or seen within the collections confirmed this in any way. Reading these diary entries showed me that the couple understood Enthoven to be a lesbian, and that they were angered by her attempts to hide and conceal this element of her private life. ‘Mischief and misunderstanding invariably follow in the wake of Gabrielle Enthoven’ scrawls Troubridge in 1931. ((Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge Papers, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin)

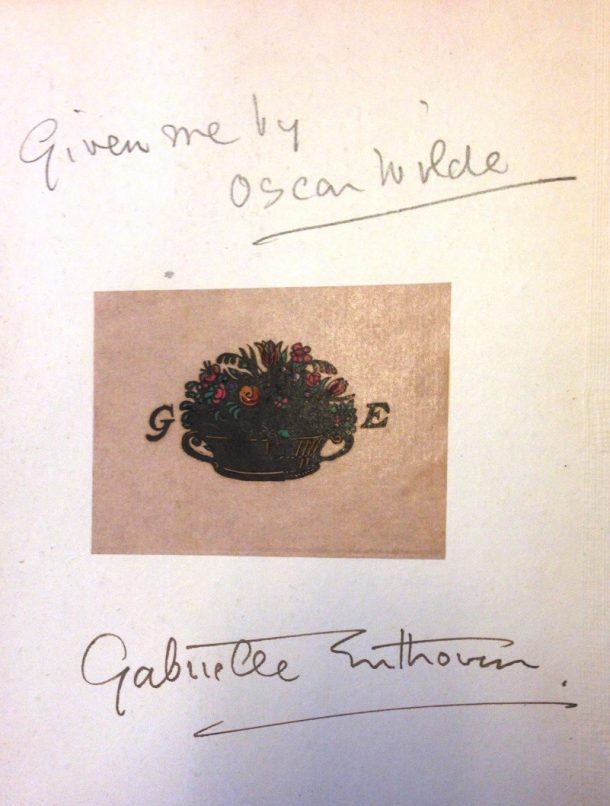

Returning to the collections at the V&A, the Museum has a number of Enthoven’s personal papers which include her holiday snapshots, correspondence and scrapbooks. Aside from the thousands of playbills and posters she collected, it is within these materials that the woman behind the collection is revealed. There is an intricately carved wooden bookplate given to Enthoven by the theatre practitioner Edward Gordon Craig: it bears her initials alongside a basket of flowers. In one of her photograph albums there is a tiny black and white photograph of an Italian street captioned ‘road leading to Duse’s house’. This appears to confirm Enthoven’s friendship with the celebrated Italian actress, Eleonora Duse. What particularly excited me in the collections was an exquisite 1898 first edition of Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Happy Prince’. Enthoven’s distinctive handwriting is written along the first page. It reads: ‘given me by Oscar Wilde.’ This small and eclectic group of materials gives a glimpse into a remarkable life spent in the company of celebrated and high-profile theatrical and literary figures.

There are also a number of letters in the Theatre and Performance Archives at the V&A addressed to and from Enthoven. This correspondence reveals that Enthoven enjoyed friendships with many gay and lesbian members of theatrical society including Sir Noël Coward, Sir John Gielgud and Edith Craig. Una Troubridge’s diaries in Texas appear to confirm Enthoven’s sexuality; or at least how this sexuality was displayed differently in private and in public. As I was delving deeper into the collections at the Museum, I came across a short but fascinating letter sent to Enthoven in 1933 from the South African actress Marda Vanne. In this letter, Vanne, the long-term partner of fellow actress Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, invites Enthoven to their home for mulled wine on Christmas Eve. She ends with the tantalising line: ‘this is a mad letter and madder still when I end it with I love you.’ (Theatre and Performance Archives, THM/14/22)

The objects both at the V&A and as far away as the Harry Ransom Center continue to shine light upon the elusive private life of an extraordinary collector. The people she corresponded with, the personal photographs and objects she amassed, and the diary entries that reference her add to the unique and complex narrative of a private life; a life distinct from her public role as collector and theatre archivist. There are things about Enthoven, such as her sexuality, that still remain ambiguous and my research and investigation into the less public aspects of her life will continue. For now, these seemingly innocent objects tell a multitude of stories and offer a glimpse into the people she knew, the people she loved, and the people she may well have wanted to avoid.