Italian Renaissance villas and gardens

Architectural details of the site and building of the Palazzo Medici in 2008, by Michelozzo (1396–1472), Florence, Italy, begun 1445.

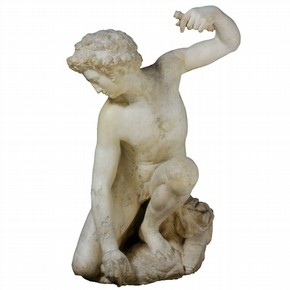

Marble Narcissus, possibly by Valerio Cioli (about 1529–99), Italy, probably Florence, about 1560 with 19th-century plaster repairs. Museum no. 7560-1861

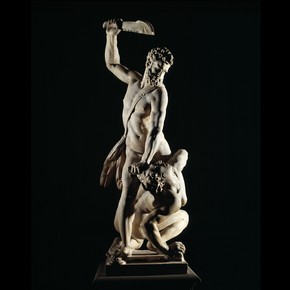

'Samson slaying a Philistine', marble statue by Giovanni Bologna, called Giambologna, Florence, Italy, about 1562. Museum no. A.7-1954. Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund

Bronze water spout, Lucca, Italy, about 1490–1520. Museum no. 7391-1860

Carved stone octagonal fountain, Padua, Italy about 1450. Museum no. 378-1895

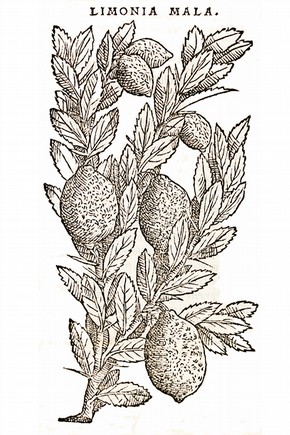

Print of Limonia Mala (lemon), by Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Italy, 1554. Museum no. 87.F.60

In the 14th century, the Italian villa was a large country house, often fortified, which stood at the heart of an agricultural estate. Some of these houses became increasingly centred around the pursuit of entertainment and leisure, and in the process were remodelled.

There was also a new type of villa that was not connected to any working estate but instead was situated just within or outside the city walls. Belonging to popes, cardinals and wealthy families, these villas were used to entertain guests and as a retreat from the noise, turbulence and unsanitary conditions of the streets and piazzas. Both types of villa were often surrounded by formal gardens. Like the buildings, these were intended to reflect the magnificence of their owner.

Although seeking a refuge from urban life, the owners of villas were greatly involved in civic activity. This meant that their villas were usually close to the main political centres: Rome, Florence, Milan and Venice. For both practical and aesthetic reasons, owners chose their site with care. The need for flowing water - to supply the villa, water the garden and power the fountains - led them to prefer hillside locations with natural springs. These sites also offered dramatic views over valleys, rivers and lakes.

Garden sculpture

Deliberately emulating the gardens of ancient Rome, owners and designers adorned the grounds of villas with an array of statuary. Excavated Roman sculpture was re-used, restored, modified or displayed in fragments and new works were commissioned. Some were copies of Roman sculpture: gods, goddesses and fantastic creatures taken from mythology. Others reflected their setting or locality, for instance a nearby river or mountain range. This marble sculpture of Narcissus was long thought to be Roman, but is now considered to possibly have been made by a sculptor and restorer called Valerio Cioli (about 1529–99). A Greek myth tells how Narcissus fell in love with his reflection in a pool. This made him a suitable subject for garden sculpture.

Giovanni Bologna, known as Giambologna (1529–1608), worked at the court of the Medici grand-dukes of Tuscany and became the most famous and influential sculptor of his day. This spectacular marble group, made for Francesco de’ Medici (1541–87), was his first major commission. In it, he achieved his ambition to create a two-figure group in movement, with several different viewpoints. Originally placed on top of a fountain in the herb garden of Francesco’s palace in Florence, the group was sent to Spain in 1601 as a diplomatic gift.

Sculpture of animals, both wild and domestic, was also popular, sometimes painted and arranged in natural poses. The placement of these works was carefully planned and integrated into the overall design of the garden. Statues were used to decorate fountains, line paths, mark the corners of compartments and act as monumental centrepieces to a design.

The use of water

During the Renaissance the manipulation of water, through spectacular fountains, rushing cascades and ingenious trickery, became the greatest manifestation of garden art. Preceded by the elegant use of water in the gardens of Moorish Spain and Sicily, Italian water features of the late 16th century reached new heights of inventiveness and technical achievement. All water play was powered by gravity and controlled by the size of pipes and their apertures. Effects ranged from powerful jets and gushing chains of water to fine mists and drips.

Perhaps fed from a cistern above, the bronze mask and pipe from the Ducal Palace at Lucca channelled water to fall clear of a wall, probably into a basin below. The coupling of a lion and a grotesque serpent brings together two decorative motifs associated with Roman antiquity.

Designers often used fountains as isolated decorative elements in a vista. This would visually link separate parts of the garden and encourage visitors to wander throughout the grounds. These water features often incorporated figure sculpture that integrated water with wider decorative schemes.

Piping water through sculpted animals, especially lions, was an ancient Roman tradition enthusiastically adopted in Renaissance Italy. This example of a fountain basin, said to have come from the courtyard of a house in Padua, has four such beasts, their mouths drilled to allow a playful flow of water.

Planting

Planting was central to the design of Italian Renaissance gardens. It was the principle means of dividing and adorning the space, and through its subtle manipulation of planting schemes - the placement and height of hedges, for example, it determined how visitors experienced a garden. The three main categories of vegetation were woodlands, orchards, and herbs and flowers. Despite a shift from the agrarian to the ornamental, many of these plants were cultivated for their usefulness. Orchards were harvested for fruit and nuts, while herbs were grown for medicinal and culinary purposes. Other plants were purely ornamental, prized for their beauty, their literary associations or their value as status symbols. The selection and range of plants increased dramatically from the 15th century as new species arrived in Italy from the Far East and the New World.

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1500–77) made an Italian translation and commentary of the work of the Greek botanist Pedanios Dioscurides: Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazerbeo libri cinque (first published in 1544). The physican broadened Dioscurides' studies by including new medicinal plants and numerous detailed woodcuts such as this one of a lemon.

Architecture

The architectural legacy of the Roman world was the inspiration for many of the structures that were integrated into Renaissance gardens. Open-air theatres, covered walkways and monuments consecrated to nymphs were modelled on ancient Roman precedents, in some cases rivalling the originals on which they were based. With their allusions to the classical world, they tested the knowledge of visitors, as well as providing somewhere to stage events or escape the heat of the sun. Much of the architecture in gardens was both decorative and structural. Terraces needed the support of vast retaining walls, often embellished with niches and sculpture and topped with elaborate balustrades, while monumental staircases were required to link the levels of gardens.

Beautiful gifts from the V&A shop

Browse the beautiful V&A Shop for exclusive gifts, jewellery, books, fashion, prints & posters, custom prints, fabrics and much more. All your purchases support the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Shop now