Bejewelled Treasures: The Al Thani Collection - About the Exhibition

21 November 2015 – 10 April 2016

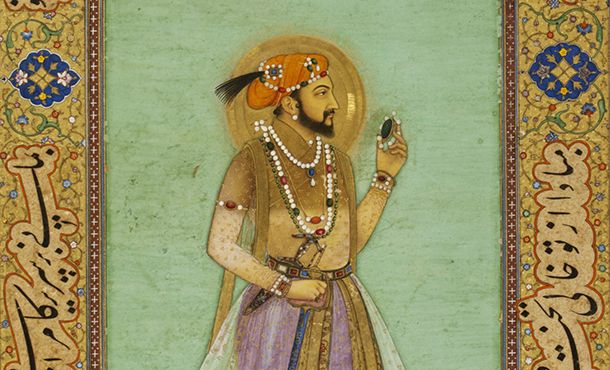

Turban ornament, © The Al Thani Collection

This exhibition showcases over one hundred exceptional jewels, jewelled artefacts and jades from the Al Thani Collection.

The pieces range in date from the early 17th century to the present day, and were made in the Indian subcontinent or inspired by India. They include spectacular precious stones, jades made for Mughal emperors and a gold tiger-head finial from the throne of the South Indian ruler Tipu Sultan.

Objects from the collections of the Nizams of Hyderabad show the influence of Western techniques and gem cutting on the work of Indian jewellers. Famous jewels from leading European houses such as Cartier reveal the more significant impact of India on Art Deco jewellery in the early 20th century.

These bejewelled treasures highlight the exceptional skills of goldsmiths within the Indian subcontinent. The most recent pieces by jewellers such as JAR and Bhagat also demonstrate that cross-cultural exchanges continue to inspire contemporary jewellery design in India and Europe.

Part of the V&A India Festival

The Treasury

From ancient times, the royal treasuries of India contained vast quantities of precious stones. Diamonds were found within the subcontinent, most famously in the southern region of Golconda. The best rubies came from Burma. Sri Lanka supplied sapphires, and from the 16th century emeralds were brought from South America to Goa, the great Eastern market for gemstones. These were of a size, colour and clarity that had never been seen before.

Early Sanskrit treatises on gemmology give precedence to nine diamond, pearl, ruby, sapphire and emerald have primacy over four other, semi-precious stones. Each represents a planet. They are sometimes combined in a 'navaratna' (nine gem) setting as an amulet.

At the Mughal court, Iranian traditions shaped the culture of the Persian-speaking elite. Here, the classification of gemstones was completely different. From the late 16th century, the most valuable stones were deep red spinels, found in Badakhshan in Central Asia. Spinels are similar to rubies, but are gemmologically distinct. The finest were appreciated for their colour, size and translucency, and were engraved with the emperors’ titles. Their spinels were not usually faceted, but the royal gem-cutters gouged out any unsightly inclusions and simply polished the irregular surface.

The Court

Mughal rule had a lasting influence on the arts of the Indian subcontinent. The Muslim emperors, originally from Central Asia, were most powerful in the late 16th and 17th centuries. They were moulded by Iranian culture and Persian literature, but they also borrowed courtly conventions from Hindu tradition.

Emblems of royalty included fly whisks held near the emperor, gold thrones and jewellery such as thumb rings, long necklaces of precious stones, and turban ornaments. When Mughal power declined, the regional rulers of the subcontinent adopted much of this regalia.

Outside the Mughal empire, one of the most distinctive courts was that of Tipu Sultan of Mysore. Objects made for him were decorated with tiger motifs, a personal emblem of his sovereignty and Muslim faith. His resistance to the British led to his ultimate defeat and death in 1799. The East India Company army looted his capital and seized his treasury. His gold throne was destroyed, but some jewelled tiger-head finials and the bird from its canopy survived.

Kundan & Enamel

In the late 16th century, Mughal court goldsmiths combined two techniques, creating a new style that is still used in traditional Indian jewellery. They set ornaments and luxury artefacts with precious stones using pure gold, or 'kundan', a historic Indian process. For the first time, they added enamel to the back or inner surfaces of ornaments. Enamelling was previously unknown in the subcontinent and was probably introduced from Europe.

The fashion spread across the empire’s northern provinces. By the 19th century, when the Mughal empire existed only in name, Jaipur in Rajasthan and Varanasi (Benares) in present-day Uttar Pradesh had become famous for their enamelling in different styles.

Each stage of making kundan jewellery is done by a specialist craftsman. The sophisticated technique allows precious stones of any size or shape to be set into designs of great complexity. Kundan can also be used to set stones in jade or crystal.

Watch a film showing the enamelling of an earring

Watch a craftsman kundan setting gems in an earring

Age of Transition

With the political upheavals of the 18th and early 19th centuries, production of traditional jewellery gradually moved out of palace workshops and into the commercial world. The process accelerated after the establishment of British rule in 1858.

In centres like Jaipur, where the maharajas actively supported the manufacture of enamelled kundan work, jewellery was increasingly bought by, or made for, Europeans.

Small independent British companies employed Indian goldsmiths, while Indian jewellers established workshops in major cities. Their craftsmen made traditional Indian jewellery or adopted Western styles and techniques with equal facility. The use of Western-cut stones was one of the most significant changes. Their perfectly regular shapes were seen to best effect in open European settings, rather than the closed settings of kundan jewellery.

A new railway network allowed jewellers to sell to patrons across the subcontinent, from the Nizams of Hyderabad in the south to Sikh maharajas in the far north.

Modernity

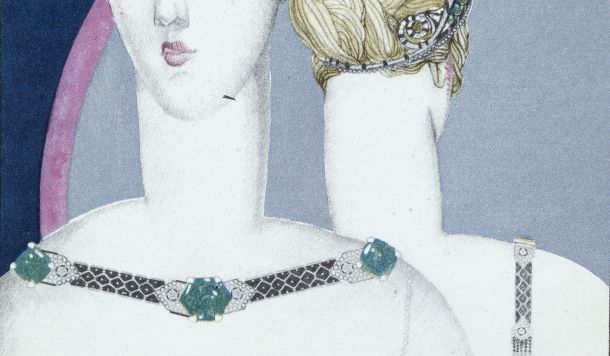

Remarkable exchanges took place between India and the West in the early 20th century. European jewellery absorbed Indian influences, while some Indian princely patrons wore contemporary Western jewellery.

In Paris, the Ballets Russes inspired a fashion for orientalism with its sensational 1910 production of Schéhérazade. The stage sets and costumes in vermilion, crimson, indigo, purple, green and gold reflected the colours of the Mughal and Iranian book paintings acquired by European collectors, including the jeweller Louis Cartier.

At the same time, India’s princes, educated by Western tutors, visited Europe and bought jewellery from leading houses such as Cartier. These relationships grew stronger when Jacques Cartier travelled to India in 1911 to attend the great Delhi Durbar, held to mark the accession of George V as Emperor of India.

Some Indian rulers later brought their own jewels to Europe to be reset. For the first time in traditional Indian jewellery, the gold associated with kingship and divinity was abandoned for the lightness of platinum.

Contemporary Masters

Outstanding jewels of the Indian past continue to inspire designers. Forms drawn from traditional kundan jewellery are adapted to settings of extraordinary lightness and delicacy. Exceptional stones cut in the Mughal manner are combined with gems shaped by the latest precision techniques.

A brooch made by Bhagat of Mumbai is set with old Golconda diamonds and smaller stones cut specially for it. An emerald in a brooch by JAR of Paris seems to float on white agate, setting off its cut and beautiful colour within a frame that echoes Mughal architecture. A necklace by Cartier has magnificent red spinels that retain their original irregular shapes, and a Bulgari ring is set with a rare engraved Mughal emerald.

All these pieces draw on the complex artistic traditions of the subcontinent, reinterpreting them in a completely modern idiom.

Sponsored by Wartski

Founded 150 years ago in North Wales, Wartski is celebrating its anniversary by sponsoring this major exhibition of jewellery. Wartski is a family business specialising in goldsmiths' work, antique jewellery, Russian works of art and especially that of Carl Fabergé. Over the years the firm has sold many outstanding masterpieces including thirteen of Fabergé’s Imperial Easter Eggs. Its customers have included six generations of the British Royal family as well as celebrated artists, musicians, actors and museum curators throughout the world. From the early 1950’s, the firm’s late chairman Kenneth Snowman published a number of scholarly books, elevating the business to a new level of excellence at which expertise and research were not by-products of the trade, but primary objectives in their own right. Wartski – The First 150 Years by Geoffrey Munn was published by ACC in May 2015.

Tickets cost £10

Concessions apply Members go free

Book now

Advance booking is recommended

What's on at the V&A?

Explore the V&A's huge range of events about the designed world, from blockbuster exhibitions to intimate displays and installations, world-class talks, casual and accredited training courses and conferences with expert contemporary speakers. Browse, search and book onto our unrivalled event programme for all ages and levels of expertise.

Book onto a great event now