Closed Exhibition - The Fabric of India

The Fabric of India: Textiles in a Changing World

Ikat sari, designed by Neeru Kumar for Tulsi, weft ikat tied and dyed by Bishwa Meher in Sonepur, Odisha, silk woven in Delhi, India, 2013. Museum no. IS.13-2015, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Industrialisation radically altered the nature of the textile trade worldwide. In the late 19th century, booming British factories were cheaply manufacturing large quantities of yarn and cloth, both to satisfy Britain’s own needs as well as for export. India, with its vast population then under the control of the British imperial government, was a tantalizing market for industrial manufacturers. By the 1890s the resulting influx of foreign fabric into India was increasingly seen as a threat to its domestic textile economy. This sparked mass protest and galvanised a political movement to liberate India from British control. In the wake of great social unrest and emerging nationhood, Indian textiles were used as symbols of protest and national identity. After winning independence from British rule in 1947, India’s new government prioritised modernisation, and textile-makers had to respond to increasingly urban environments. Over the following years, they adapted their skills to ensure their continued cultural, economic and global significance.

Cloth and Crisis

Choli, cotton, industrially woven and printed in England, tailored in Bombay, about 1871. Museum no. 8250 (IS), © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Britain began to export machine-made yarn and cloth to India in the 1780s. Encouraging exports of low-cost fabric and imposing tariffs on imports of Indian cloth enabled Britain’s textile industry to grow rapidly but severely hampered the development of India’s own industry. The importance of manufacturing and trade among nations was promoted through the Great Exhibition of 1851 held in London and subsequent international exhibitions held across Europe. Cloth manufactured in the Lancashire mills soon replaced all but the extremely fine or extremely rough Indian fabrics, causing mass unemployment and hardship for India’s spinners and weavers.

Fabric and Freedom

Lengths of khadi (detail), plain-woven cotton, Gujarat, India, about 1867. Museum nos. 0120 (IS), 5955 (IS), © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

British exploitation of India’s economy and people led to the swadeshi (‘own country’) movement of the 1890s. Swadeshi urged the nation to boycott foreign goods and buy Indian products. The principle of self-reliance influenced the nationalist leader Mohandas Gandhi in his call for swaraj (‘self-rule’). Gandhi appealed to the Indian people to spin, weave and wear khadi – a fabric hand-woven from hand-spun cotton thread. He believed this would bring employment to the masses and alleviate poverty. In 1921, Indian nationalists adopted khadi cloth as a symbol of resistance and incorporated the spinning wheel into the design of their flag.

Video: The Road to Independence

Gandhi mobilised the masses through protest marches and acts of civil disobedience. As the independence movement gained momentum, the visual impact of his clothing and the large crowds wearing white ‘Gandhi’ caps became a powerful tool of protest. Jawaharlal Nehru successfully led the nation to independence on 15 August 1947. The film below contains extracts from the film Mahatma (1969), and includes original footage of the period.

Films Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India

Moving Forward

Mughal-inspired coat (detail), designed by Brigitte Singh, block printed and quilted cotton, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, 2014. Given by Brigitte Singh. Museum no. IS 15-2015, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

India’s independence in 1947 brought the challenges of industrialisation and modernisation. Alongside a drive to increase factory production to clothe India’s vast population, the government set up the All India Handloom Board in 1952 to nurture hand-weaving and other textile crafts. In 1961, the National Institute of Design was established and designers began to play a key role in the modernising process. Today many independent studios are producing hand-made textiles, while cinema and fashion are popularising traditional techniques.

International Impact

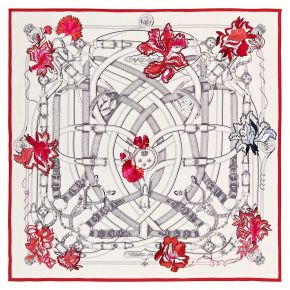

Cavalcadour Fleuri shawl, designed by Henri d’Origny (b.1934) for Hermès, Paris, embroidered at Les Ateliers 2M, Mumbai, cashmere embroidered with silk, Paris, 2014

Today, Indian craftsmanship remains in demand across the globe. International designers as well as British high street brands use Indian skills to produce garments with hand-beading and embroidery. Fashion brands sometimes choose not to promote their production in India as this is often associated with cheap mass-manufactured garments and the exploitation of labour. By contrast, the designers displayed in International Impact have cultivated mutually beneficial business relationships with the Indian artisans they employ. They appreciate the great diversity and quality of skills available in India and the ability to create innovative designs for an international clientele.

Beautiful gifts from the V&A shop

Browse the beautiful V&A Shop for exclusive gifts, jewellery, books, fashion, prints & posters, custom prints, fabrics and much more. All your purchases support the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Shop now