Conservation Journal

October 1992 Issue 05

Closed for summer or shuttered for good? The RCA/V&A conservation course study trip 1992

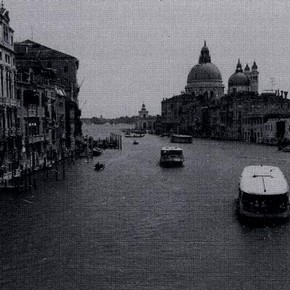

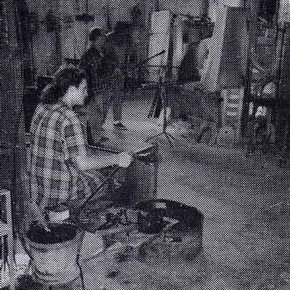

Each year students on the RCA/V&A Conservation Course and the Course Leader, Alan Cummings, make a study trip of about a week to learn something of the culture, collections and conservation practice outside South Kensington. In the first year of the Course, the destination was Scotland and last year the trip was to Amsterdam. This year, Alan and seven students spent five days in Venice, which proved to be a perfect place for a study trip, providing just the right balance of the educational and the simply enjoyable. During our stay we visited a number of laboratories and museums both collectively and individually. The neighbouring islands of Murano and Burano provided an opportunity for those studying glass and textiles to experience how the ancient crafts of glass blowing and lacemaking are still being practised today.

On our first day, John Millerchip, the representative of the Venice in Peril Fund (the British conservation organisation working under the aegis of UNESCO) met us at our hotel. He gave us a sound introduction to Venice, explaining the involvement of Venice in Peril and other international organisations, the administrative structure which controls conservation work and the fundamental problems faced by the city and its people. His talk provided a basis for the rest of the week. It helped us to look at the city from an informed point of view and appreciate the complexity of what we saw.

We were assured that the threat of erosion and flooding from the waters of the lagoon was under control, thus securing the foundations of the city. Pollution from nearby industrial centres has been perhaps a greater problem in recent decades but it is clear that this is now also becoming less serious with new environmental controls. No less a threat, however, comes from simple neglect, sometimes deliberate. This is particularly a concern for the many ordinary buildings which make up the backstreets and areas not often seen by the day visitors, who tend to congregate around the familiar landmarks of the Grand Canal. These ordinary buildings are the essence of the city and, whilst many contribute to the genteel shabbiness which gives Venice its unique character, others have been left to decay to such an extent that they might be better described as an eyesore. It seems that there is little incentive for the owners of these buildings to maintain them regularly. It can be financially beneficial to allow them to deteriorate, relying on the availability of grants from various sources to pay - but only eventually - for repairs and conservation. The air of neglect is accentuated by the fact that many of the native Venetians have left the city, driven out by extraordinarily high rents, property prices and unemployment. During our visit, much of the remaining Venetian population was away on vacation. The majority of tourists make short visits to the city from elsewhere and so the streets seemed almost deserted in the evenings, when the day trippers had left. In terms of conservation, Venice could be considered to be one enormous conservation site with two very different faces. Much has been done in the areas around the Grand Canal to restore the elaborately ornate buildings, gilded and lavishly decorated with wall paintings, a programme much in evidence judging by the amount of scaffolding and plastic sheeting surrounding several central landmarks. Little seems to be being done, however, for the fabric of the rest of the city. Wandering the backstreets with map in hand, trying to follow the logic of its builders and avoid getting lost, there are occasional examples of conservation in action, mainly connected with the churches. Here it is possible to enter through the plastic and watch the conservation of stained glass, as in the Madonna dell' Orto, or climb, if you have the nerve, the outside scaffolding of S Zulian to observe the cleaning and conservation of the grimy exterior, or even to enter the Sala della Musica of the Ospdaletto and see the wonderful, completed work of its painted interior. It was obvious from these visits that decisions about conservation in the city need to be made very carefully. Those responsible must consider how far buildings can be cleaned, conserved and restored without destroying their individual character and the character of the city as a whole. Would a pristine Venice have the same magic as the rather dilapidated sight we see today? When do you step in to stop genteel shabbiness becoming dereliction? In a city (or is it a vast living museum?) which is important to the whole world, who should ultimately foot the conservation bill? Conservation visits made, either collectively or individually:-

Venice: S Zulian: Mr John Millerchip

-

Sala della Musica: Mr John Millerchip

-

Civici Musei Veneziani: S Marcella Ansaldi

-

Laboratorio Scientifico della Misericordia: Dr Vasco Fassina

-

Peggy Gugenheim Collection: Dr Philip Rylands

-

Murano: Stazione Sperimentale del Vetro: Dott Marco Verita

-

Glass blowing factory: Dott Marco Verita

-

Glass museum Burano: Lacemaking

Our thanks are extended to everyone who generously gave up their time to speak to us and show us around during our stay.

October 1992 Issue 05

- Editorial

- Working with students on collection condition surveys at Blythe House

- The AMECP project: prevention is better than cure

- Conservation & rotating displays in the Nehru Gallery of Indian art

- The Raphael cartoons for the Vatican tapestries: conservation treatments past & proposed

- Exchange visit to the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

- A review of the interim symposium of the ICOM leather & related materials group

- Closed for summer or shuttered for good? The RCA/V&A conservation course study trip 1992