Conservation Journal

January 1993 Issue 06

Editorial

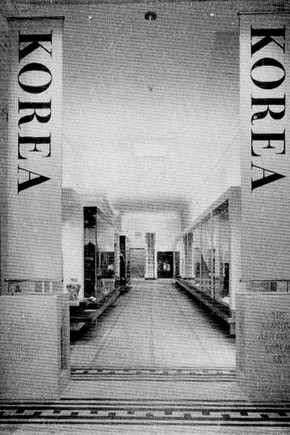

The photograph on this page shows the Samsung Gallery of Korean Art, a new display that opened at the V&A at the beginning of December. A new gallery project calls on a range of conservation skills; advising on and testing showcase materials, specifying and monitoring the environment, cleaning, repair and restoration of artefacts, and support and mounting of the exhibits. Management decisions about which objects to treat in what order merge into ethical decisions about how extensive cleaning or reintegration should be.

At the V&A there is close involvement of conservators at all stages of a new gallery project. This is an indication of the changes that have taken place in the profession over the last 15 years. But care should be taken to note where these changes could lead.

It is now accepted that the conservator must know something about monitoring and control of the environment, should be able to devise programmes of preventive conservation and be knowledgeable about appropriate methods of storage and display. In some institutions this has become the limited area of activity of the person called conservator. In a number of major museums, the role of the curator has been changing so that physical collections management has become a dominant activity. In this way the job descriptions of conservator and curator have begun to overlap in a way that they did not before. At the same time it has become more common for collections management issues to predominate in conservation training courses, to the exclusion of the development of practical interventive skills. If the trend towards the conservator as guardian of collections is continued to its extreme, there is a real danger of reinventing the curator and of losing a valuable and creative distinction. There could follow a loss of skills that are not easy to develop and which are needed as collections are made more accessible to wider audiences (or as historic houses continue to catch fire).

The necessary distinction is that conservators do physically intervene with objects.

The cynical would reply 'Yes, and look at all the damage they have done'. But it would be more constructive to look at the far greater good that practical intervention provides. Beyond merely preventing objects from disintegrating, it enables a greater understanding and enjoyment of historic objects as well as providing information valuable to historians of art and technology. Damage only results from lack of knowledge or lack of skills and insufficient time given to consideration of the ethical issues.

Within this Department the development of practical skills is considered paramount and this has dictated the shape of the post-graduate course. The design of new accommodation for the Conservation Department is based on the primacy of practical work. Much of the knowledge of materials science and the effect of environment stems from an active but intelligent physical interaction with real objects. I believe that with the right training the subject specialist with practical experience makes the best manager.

The aim is to arrive at a balance between preventive and interventive conservation. A balance which is reflected in this issue of the Journal. In a new gallery project a low-cost preventive measure will slow down the deterioration caused by light. Carefully considered intervention into an album of photographs will allow it to be enjoyed without damaging it. The survey and investigation of plastic materials will lead to better methods of storage and display, as well as the development of safe methods of cleaning and repair.

January 1993 Issue 06

- Editorial

- The conservation of Roger Fenton's album of Crimean photographs

- A question of principle

- A survey of plastic objects at The Victoria & Albert Museum

- Preventive conservation in practice

- Introducing the new course tutor

- Textile conservation in Russia

- Assessment RCA/V&A conservation course: science for conservators