Conservation Journal

January 1993 Issue 06

The conservation of Roger Fenton's album of Crimean photographs

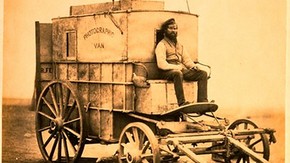

Roger Fenton's Photographic Van, 1855. After conservation. Museum no. Ph.263-1979 (click image for larger version)

Roger Fenton was, in the words of Mark Haworth-Booth (the V&A's curator of photography) 'the Ian Botham of photography'. He was an all-rounder in the early decades of photography; he was a still life, architectural and landscape photographer, the British Museum's first official photographer, principal founder of the Photographic Society of London and royal portrait photographer. In addition, together with the work of James Robertson, Fenton's 360 images of the Crimean War represent the first extensive photographic war reportage.

The album consists of 132 salt prints, printed from wet collodion glass plate negatives. This process 'required an enormous amount of equipment as the plates had to be prepared exposed, and developed while the collodion was still moist'1. Fenton took a horse-drawn 'Photographic Van' to the Crimea (Fig. 1) to carry his equipment and act as a darkroom, as well as provide him with accommodation. This photographic van 'formed a conspicuous target and on several occasions drew the fire of the Russian batteries'2 . The heat in the van was extreme and in addition, Fenton nearly died from the fumes of the developing and fixing chemicals.

Fig 2. Photograph of 'Major General Estcourt', before conservation. Museum no. Ph.343-1979 (click image for larger version)

Most of the photographs in the V&A's album depict individuals and groups of soldiers, some obviously posed (exposure time was 10-15 seconds), others more 'natural' (Fig. 2). Fenton's work in the Crimea was commissioned by Thomas Agnew & Sons (the art dealers and print publishers) and assisted by royal patronage. Prints pasted on paper mounts with engraved titles were sold by Agnews; wood engravings of some photographs were printed in The Illustrated London News3. He was not allowed to photograph dead bodies or gruesome scenes, partly because of the sensibilities of the public at home and partly because he was to 'give convincing proof of the well-being of the troops after the disasters of the preceding winter, which had caused the downfall of the government'4 .

The album was acquired by the Museum in 1979. The prints are mounted recto and verso on 64 leaves of differing types of paper, from a yellow, very shiny, highly glazed paper to a creamier, thicker, softer paper.

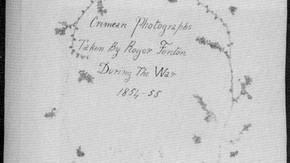

The volume had been disbound and although there were remains of sewing thread in the folds, the leaves were loose. The leaves were all single, with return guards, that is, the leaves had an extra folded strip of about 10 mm at the spine edge. The binding was quarter green cloth with marbled paper sides and had been very crudely repaired with red velvet over the spine and board corners (Fig. 3). The leaves were loose within the binding when the volume was acquired, and it is not known whether they were ever bound into the accompanying binding, either originally or at a later date. On the first page in the top right corner is the manuscript inscription: 'Eva Katherine Fenton / Her Book 1874' and in the centre in the same hand: 'Crimean Photographs / Taken by Roger Fenton / During the War / 1854-1855', surrounded by dried foliage (Fig. 4). Eva Fenton was Fenton's daughter.

Condition

The photographs had been examined by Elizabeth Martin, senior photographic conservator, and were in a good, stable condition, requiring no conservation. The support paper was dirty, torn, damaged and vulnerable. In its present state, this important volume was subject to restrictions for readers in the Print Room and could not be displayed. There had been discussion in 1989 between the Prints Drawings and Paintings Collection and Paper and Book Conservation Sections as to what to do with the album.

Textblock treatment

Given the stability of the photographs, the major conservation considerations were the support paper and the subsequent format of the album. Whatever the final treatment, the support paper required conservation. The surface dirt was removed with a Mars Steadier vinyl eraser. The support paper was repaired with a variety of Japanese tissues and papers, reflecting the different types of paper in the album. Tengujo and mino toned with Winsor and Newton watercolours were the most widely used, together with another beautiful kozo tissue made by Tim Barrett of Kalamazoo Papers, which comes in sheets of tear-off strips in two different widths, and is available in two weights. The strips can easily be torn or water-torn; in fact for the shortfibred paper which was being repaired, the fibre length was almost too long and fibrillated and had to be teased away. Wheat starch paste, used fairly dry, was the adhesive for the majority of repairs, except for two leaves of highly glazed paper which would have been very susceptible to an aqueous adhesive. For these, lens tissue coated with isinglass was used, which was reactivated over the repair paper with just a hint of moisture and boned down well5 .

The dried foliage on the titlepage had to flex as the leaf was turned and therefore it was decided not to read here the whole length of the crumbling and fragile stem, leaves and flowers. Instead, to introduce a degree of flexibility when the leaf is turned and prevent further cracking and loss, the foliage was caught down with little bridges of Japanese paper (3-5 mm long; 0.5-1 mm wide), pasted with wheat starch paste, loose over the stem to allow for movement (Fig. 5).

Several photographs were missing from the volume, having been removed for display purposes (for 'The Golden Age of British Photography, 1834-1900' exhibition at the V&A in 1984). These were found and reunited with the rest of the album; they were attached with two Japanese tissue hinges at head and tail, with a very dry wheat starch paste. This highlighted the possible pitfalls of removing items from albums and reinforced the importance of the album-format as a safe storage vehicle.

Binding treatment

Once the support leaves were repaired, the treatment options were:

-

Repair the cover, resew the leaves and reattach into the present cover

-

Make a blank book and attach the leaves into that

-

Make a series of blank pamphlets and attach the leaves into them

-

Mount the leaves individually and treat the volume as a series of single items

At the recent IPC Manchester Conference half-day session on the ethical considerations connected with the conservation of albums, the dilemma of these artefacts was neatly summarised as the tension between original intention versus present usage.

In the case of the Fenton album, weighed against the treatment options were conflicting demands on the volume, namely:

-

The images must be available to readers in a form whereby they can be handled safely

-

The images must be available for exhibition, both within the Museum and externally

-

The images should be retained in book form as closely as possible

Treatment discussion

To mount each object and treat the volume as a series of single objects denies the 'integrity of the object' as an album, whether it was put together and owned by Fenton's daughter or not. However, to rebind it into the covers in which it is housed would produce a very vulnerable structure, as the fragile support leaves would be constantly handled and the sewing structure would be very flimsy. In addition there is no evidence that this was its original or even a later binding. Attaching the leaves into a blank book has been a successful option for another album, of William Callow drawings, but the emphasis was different in that case; the album had been made by the HMSO after the drawings were acquired by the Museum, and it was not functioning well. For the Fenton album, this solution would not address the display requirement, as only one image would be available for exhibition at a time.

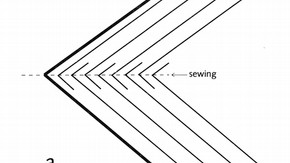

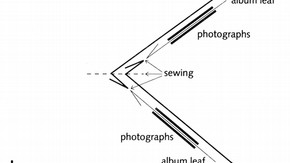

Given the display requirements and the handling demands on fragile support paper, another possibility was to make a series of 'fascicules' and attach the leaves to those. Fascicule were developed by Christopher Clarkson when at the Conservation Department of the Bodleian Library Oxford, for the storage of ephemera and loose, individual paper items. They are single section pamphlet bindings, constructed of a number of single leaves with return guards, simply sewn through the centre, with an acid-free stiff paper cover (Fig. 6a). Different size items can then be hinged to each of the return guards. The leaves of the fascicule give support to the loose items and the support leaves are turned rather than the objects. At the Bodleian, these fascicules are made in standard sizes, with corresponding boxes to accommodate several at a time.

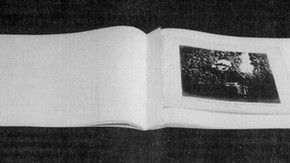

For the Fenton album, this option fulfilled the conflicting demands of accessibility to readers and availability for display. The idea of fascicules was modified, in that firstly the fascicules were made out of 120 gsm Silversafe, which is a non-buffered, pure cotton paper specifically developed for the storage of photographs. Secondly, rather than hinge each image in with Japanese tissue, the original return guard of each leaf was utilised. Each fascicule leaf was constructed with a folded return guard and then each leaf was three-hole sewn to that (Figs. 6b & 7).

The advantages of this system are that the images and original support paper can be handled safely without wear to either. Since each leaf is supported by a larger leaf of Silversafe, protection is afforded to the still vulnerable support paper, and much handling can be accommodated (given that there are images recto and verso) without the original paper being handled. The Silversafe also acts as interleaving between the photographs, preventing any abrasion between image surfaces. As there are nine fascicules, several images can be consulted or displayed together whilst maintaining some semblance of book form. If it is deemed essential to display an individually mounted and framed photograph, the leaf can be removed from the fascicule by releasing the sewing thread, and it can then be resewn into the fascicule after the exhibition.

Fig. 7. Photograph of 'Major General Estcourt', after conservation in a fascicule (click image for larger version)

The method is completely reversible, and so if it is proven that the quarter green cloth cover was the original binding, the fascicules can very easily be disbound and the leaves rebound. Lastly, it is relatively quick to do. The fascicules will be housed in a drop-back double-walled Library of Congress type conservation box.

Conclusion

As ever, this represents a particular solution for a unique set of practical, custodial and ethical problems. For example, I would not advocate this solution for a robust binding which was not already disbound or for a binding which could categorically be proven to have been assembled or constructed by a next of kin. In the case of the Fenton album, fasciculing offered a good compromise between the present life and demands of use and the book form.

References

1. Gernsheim, H.,A Concise History of Photography, Dover Publications, Inc, New York, 1986, p. 20

2. Ibid, p.64

3. Newhall, B., The History of Photography, Becker & Warburg, London, 1982, pp. 85-8

4. Gernsheim, p. 64

5. Petukhova, T., 'Potential Applications of Isinglass Adhesive for Paper Conservation', AIC Book and Paper Group Annual, Washington, 1989, pp. 58-61

January 1993 Issue 06

- Editorial

- The conservation of Roger Fenton's album of Crimean photographs

- A question of principle

- A survey of plastic objects at The Victoria & Albert Museum

- Preventive conservation in practice

- Introducing the new course tutor

- Textile conservation in Russia

- Assessment RCA/V&A conservation course: science for conservators