Conservation Journal

July 1993 Issue 08

Protecting Tutankhamun

Archeologist Howard Carter's discovery and clearance of the tomb of the boy-pharaoh Tutankhamun (who ruled Egypt probably from 1333 to 1323 BC) began seventy years ago - when Carter caught his first candle-lit glimpse of the 'wonderful things' piled up in the antechamber on 26 November 1922. The clearance took nearly ten years - the final objects were railed and shipped to Cairo in the spring of 1932 - and attracted more world-wide publicity than any other single 'moment' in the history of science up until that time. The publicity (accompanied by Harry Burton's magnificent monochrome photographs of the tomb's interior) concentrated on the objects themselves - a mid-1920s outbreak of 'Tutmania' was one of the spin-offs - on the so-called 'curse of the pharaohs', and on the life and times of King Tut. Very little was written about the meticulous classification and conservation of the artefacts, and yet if it had not been for the on-the-spot efforts of chemist Alfred Lucas (one of Carter's team of experts), many of the objects which are now on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo would never have made the journey from the Valley of the Kings up the Nile to Cairo.

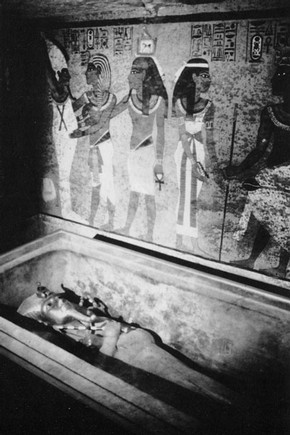

Fig 1. The burial chamber of Tutankhamun today, in the Valley of the Kings - with humidity damage to the end wall (click image for larger version)

In the antechamber alone (the first room to be cleared, in the 1922-3, and 1923-4 seasons) there were wooden sculptures, chariots, pieces of furniture, inscribed and painted boxes, chests crammed full of delicate fabrics, jewellery, cosmetics, ceramic vessels full of foodstuffs and wines, and hundreds of small articles of clothing - such as sandals - which almost fell apart at a touch. There were even more fragile linen gloves, and dried wreaths of flowers (possibly thrown into the antechamber at the last minute, by Tut's young widow Ankhesenamun) which, like the fabrics, had to be stabilised and conserved with paraffin wax before they could be moved - a great test for the budding science of conservation, and the subject of learned journal articles by Lucas in 1942 and 1947. The antechamber, which Carter likened to the 'property room of an opera of a vanished civilization', was literally full of the King's favourite things, buried with him in the belief that his spirit-form could enjoy them second time around in the after-life.

As the tomb was being cleared, the team reported that they could hear the cracks and creaks of objects adjusting to the new environmental conditions - when the air of modern Egypt encountered an atmosphere which had been sealed up for 3245 years. It is a tribute to Lucas's often improvised conservation skills, in the nearby 'laboratory tomb' (specially kitted out for the purpose), that of the many thousands of objects discovered only a quarter of one per cent of them were lost. Without preliminary conservation, Carter estimated, barely ten per cent of the objects would have been fit for public display.

So, when we were making the BBC television series 'The Face of Tutankhamun', first broadcast in November-December 1992, we were determined to redress the historical balance by emphasizing Lucas's largely unsung contribution to the excavation. We were helped in this by the discovery of much documentary film footage of Lucas at work (on the wreaths, for example) in the archives of the Metropolitan Museum in New York: the pictures could carry the story. And when we were deciding how to conclude the five-part series, we resolved to devote the entire last episode - eventually to be called 'Heads in the Sand' - to the after-life of the artefacts in the seventy years between the 1920s and the present day: this would mean looking closely at the conservation policy of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. We agreed that a central theme of the episode would be the conflicting demands of the tourist industry (a major contributor to the Egyptian economy) and the conservation of King Tut's treasures. This theme was bound to be controversial. But Egyptologists who had worked in both the Museum and the Valley of the Kings strongly encouraged us to examine it, provided our aim was to enhance the viewers' understanding of the issues rather than merely to exploit it. There had been many recent articles (for example in The Times and The Independent) about the parlous state of the 'Tutankhamun' galleries in the Egyptian Museum. But the question was: how were we to present the problem in a constructive as well as informative way?

My script - spoken over images of crowds of tourists queuing up to gaze at Carter's 'wonderful things' - introduced the sheer scale of the conservation dilemma:

'The Egyptian Museum in Cairo was designed in neo-classical style by the French in 1902, and has long outlived its usefulness as a workable Museum. It has recently been described as a dusty relic of colonialism and the world's worst display of the world's finest treasures. The contents of Tutankhamun's tomb are still exhibited in display cases dating from Howard Carter's time, with labels you can hardly read, in an atmosphere more akin to a railway station than a national museum. There's no humidity control, internal pollution levels are eighty per cent of those outside, the roof leaks and some of the cases are buckling under their own weight - like this one above the great golden shrine. Exhaust fumes from the gridlocked city-centre traffic just outside are eating away at the gilded surfaces...'

We then showed images of water leaking through an open window onto a display case below, which in turn was leaking onto the magnificent jewellery once worn around Tutankhamun's neck: the metal clasps had, quite literally, rusted onto the hessian display cloth.

The commentary then discussed various options which have been mooted in recent years: a refurbished gallery, or a special extension, or even a new museum. But questions of funding - in a Third World economy - and of the politics of International Aid had complicated matters, and in the past resulted in indecisiveness.

The next sequence, the most controversial in the entire series, went behind the scenes to show a young conservator attempting to repair a wooden portrait-bust of the pharaoh himself. The sculpted plaster on his face was deteriorating fast, and the chosen remedy was to inject a thin layer of soluble adhesive between the plaster and the wood. The script continued:

'The plaster is pushed back into place, but it cracks under the pressure... Things go from bad to worse and the conservator tries to rescue the situation... In the course of two minutes - and with the best intentions - more damage has been done than in the last three thousand years. Multiply that by their number of antiquities and monuments in Egypt, and you have a crisis.'

While we were filming this sequence, we were faced with an ethical dilemma of our own. Our intention was to film in the conservation workshops of the Egyptian Museum, to interview various conservators, and to finish on a plea for international understanding, expertise and support for training. But while we were filming, the young conservator - who was understandably nervous, working as she was under spotlights and with the camera turning over - made a series of mistakes: and in the process of trying to correct these mistakes, she made matters considerably worse. Would she have made these mistakes if we were not present? Should we be excited at an example of 'good television' (as the saying goes), or appalled at the damage she was doing? Should we stop filming, to allow her to compose herself and take advice from the senior conservators who were standing by in their white coats, and watching? Or should we continue, in the knowledge that this was a graphic example of the very problem we were trying to present? Above all, what right did we - as British film-makers - have, to pass judgement on a young Egyptian conservator who (as I put it), 'with the best of intentions', was simply trying hard to go about her business. In short, the filming of the sequence had turned into a mirror-image of the central theme of the programme.

Finally, we went ahead and made the 'conservation of the wooden mannequin figure' a key sequence in our film. We put various matters arising to senior officials, conservators and even a minister: so they had the 'right to reply'. In the end we felt that this small, but dramatic, story both illustrated and epitomised the problems faced by a Museum which houses some of the greatest treasures from the history of art, but lacks the resources (and, through no fault of its own, the latest expertise) to look after them. The rest of the programme examined even bigger conservation problems - the Sphinx, the entire Valley of the Kings: you don't get much bigger than those - and found some examples of good practice for comparison (such as the Getty/Nefertari project, begun in 1986, and the Conservation Practice's master plan for the area surrounding the Sphinx at Giza). At one stage, we considered featuring the V&A's own textile conservation workshops - since the Museum's collection includes some short lengths of fabric from Tutankhamun's tomb, possibly donated when Howard Carter lectured in the Lecture Theatre on colour in ancient Egypt: but, in television terms, it seemed more effective to find examples of best practice actually happening in Egypt.

In the period since the programme was broadcast, I have had (literally) scores of letters about that hapless young conservator in Cairo. A few reckoned that we were unfair to dwell on her misfortune - to present a general problem in such an individual way, to confuse a structural dilemma with a personal one. But most (especially from Egyptologists) welcomed both the sequence and the contents of the episode as a whole: they felt that Heads in the Sand had drawn attention to a serious, delicate and neglected aspect of the subject - in a mature way - and might even help to prick the conscience of the West as well as opening up the debate to the widest possible audience. I sincerely hope that they were right. A fifty-minute primetime programme about the practice and ethics of conservation - in a non-Western culture - is certainly unusual. But will it achieve more than just upsetting the viewers on a Friday night before they switch over to Jonathan Ross and think about something else? Only time will tell..

July 1993 Issue 08

- Editorial

- Polychrome & petrographical analysis of the De Lucy effigy

- Protecting Tutankhamun

- Conservation department group photograph, 1993

- Hankyu - the final analysis? A new approach to condition reporting for loans

- Camille Silvy, 'River Scene, France'

- A conservation treatment to remove residual iron from platinum prints

- Film '93: a visit to BFI/NFTVA J Paul Getty Jr conservation centre, Berkhamsted

- The class of '93