Conservation Journal

January 1994 Issue 10

Conservation ethics workshop

Fig.1. The Fonthill Organ before it was radically altered, about 1860. (click image for larger version)

In September 1993 a two-day workshop was held at the V&A on the Ethical Principles of Intervention in the Conservation Department. The Department was very fortunate to have Dr Susan Wilsmore, a lecturer in philosophy with a specific interest in conservation issues, offer to lead the workshop and to invite a number of experts from other professions to contribute. Her knowledge of current practices in the Conservation Department was gained in a preliminary study based on interviews with individual conservators. As a first step in a continuing process of examination of ethical issues in conservation the workshop was conceived primarily as training for in-house conservators and, in order to further this end, the aim was to create a forum for discussion between conservators, curators and other professional groups.

The list of objectives for the workshop was comprehensive:

-

To identify the underlying principles that currently govern conservation practice in the Museum and to recommend principles that should do so.

-

To produce a rational method of reconciling conflict.

-

To fully understand the implications of conservation treatments with regard to changing the identity of an object.

-

To compare ethical decision-making in other professions, namely the law, medicine, dentistry and business.

-

To be able to apply some of the terms of moral philosophy - as a tool in examining conservation principles.

Fig.2. Conservation of the design of an Art Nouveau leather covered chair. (click image for larger version)

An uneasiness about what was perceived as the sometimes ad hoc and subjective nature of decision-making, as well as the realisation that forces outside the control of the contractor were having a significant influence on treatment decisions, were among the reasons which prompted the Department to commit a considerable amount of time to discuss these issues. Dr Wilsmore responded to these concerns with her view that if principles could not hold up under rational discourse then they were indefensible and, under scrutiny by others, the resulting decisions upon which they were based could not be justified.

The short presentations of case histories, which took up the first day of the workshop, brought a number of issues into focus, which were characterised, in many instances, by loosely defined criteria which allowed for a flexible approach by the conservator.

-

Was respect for the creator's intentions, as opposed to his actions, paramount and therefore did preserving the idea or the design of an object override survival of the actual material?

-

What point of an object's history should be selected for preservation and once identified how could we know what the object's former appearance actually was?

-

Should the function of an object, as utilitarian, for example, be a determining factor in deciding treatment?

-

Are there dangers inherent in allowing documentation to be used as an alternative to preserving the information held in the object?

-

To what degree is an audience misled by replacement of missing parts and how can communication about this be encouraged?

-

How far should time factors be allowed to influence decisions?

-

How large a part should the museum play in the life of an object?

-

Should the skill of a conservator be a factor in deciding treatment?

Fig.3. Lacquer commode, Museum no. 1094-1882. How should we define the original finish on 18th century French furniture? (click image for larger version)

At this point in the workshop it was clear that we were producing many more questions than answers!

Now that the current situation had been described the next step was to gather into small groups to come up with some ideas on what to do about it. Almost everyone wanted more discussion to take place, both within the Department and between curators and conservators. Another popular wish was for a checklist of criteria for decision-making that would be a practical tool for the conservator and for training. Promoting communication with all of our clients was recommended and areas for consideration included: museum labelling, a conservation exhibition and literature. Many felt that they needed training, particularly in problem-solving. Making documentation more accessible was considered to be a good way of addressing the issue of conservator accountability and also a method of involving the curator on a formal basis.

Now it was time to see how ethical issues had been handled by other professions. Could they offer us some guidance? It was clear that many, although not all, had regulated their profession by means of a register, had established a body to set standards and had decided where their ethical responsibilities lay. In the case of the law, a set of principles were continuously up-dated by adding case judgement to the Code of Practice. As a result the Code of Practice extended to many pages. In medicine, another route had been chosen, going back to general principles based on the autonomy of the individual as a rational human being able to make decisions responsibly. Business ethics, too, relied on personal morality. It was clear that there were a number of options for the conservation profession, however Ian Betteridge, a lecturer in medical ethics, advised us to opt for general principles rather than a Code of Practice.

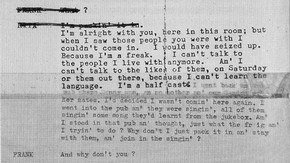

Fig.4. Illustration from the typescript of the play 'Educating Rita' by Willy Russell in the Theatre Museum's collection. Museum number S.3 1991 (click image for larger version)

The importance of deciding where our ethical responsibilities lay (in our case, with the objects or with the museum?) was repeatedly emphasised. Daniel Alexander, a Barrister-at-law, talked about recent legislation on Moral Rights and indicated that the law could not offer us much guidance at the present time due to the fact that only a handful of cases had come to the courts. He suggested that instead our duties lay in our capacity as advisers to the judiciary in establishing precedent cases upon which the law would be based.

As a first step in a continuing process there was general satisfaction with the workshop. The structure worked well as a forum for discussion and the Department is very grateful to the curators and members' of other professions for their active participation which stimulated a lively response from the floor. In terms of achieving our objectives there is cause perhaps for some disappointment. Admittedly, it was a tall order but progress was certainly made and the points remain on the Departmental agenda. Dr Wilsmore succeeded in bringing a fresh and objective viewpoint to the proceedings, which included a certain amount of criticism. This experience in itself has provided a valuable model for our profession. The organisers have observed with some satisfaction that, as a result of the intensive intellectual activity which took place preceding and during the workshop, ethics have become a vital issue of daily interest to conservators at the V&A. The outcome of the workshop has already had repercussions, for example, in the recent drafting of the new grading guidance for the Department.

Finally, all that remained was to carry over into our working life the suggestions made at the workshop. In order to do this, a small working group consisting of members of the Department was set up. The first priority was to draft a checklist of procedures to be followed before deciding treatment. The draft is currently circulating the Department to be added to and commented on by conservators of each specialisation. It is the intention to tackle other issues by proposing mechanisms and putting them forward to the Department for its consideration, these include mechanisms for promoting conservator-curator dialogue, accountability to clients, accessibility of documentation, quality assurance and training. It became clear right away that the remit of the group crossed over into current preoccupation of other groups, such as those with responsibility for documentation, for revising the Museum's Code of Conduct, and for setting standards or performance indicators.

Co-ordination with these bodies will be an additional responsibility of the working group. An update on the progress made by this group and by the Department as a whole in achieving our objectives will be presented by Dr Jonathan Ashley-Smith at the conference, 'Restoration - Is It Acceptable?' to be held at the British Museum in November 1994.

January 1994 Issue 10

- Editorial

- Conservation ethics workshop

- A curator's view of the ethics workshop

- Flattening large rolled paper objects

- Beating unwanted guests

- Stained glass in Eastern Europe

- The Sherman Fairchild Center for objects conservation: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- RCA/V&A conservation course abstracts: materials & techniques essays 1992/3 & MPhil theses 1993