Conservation Journal

April 1995 Issue 15

The Parkes collection of Japanese paper

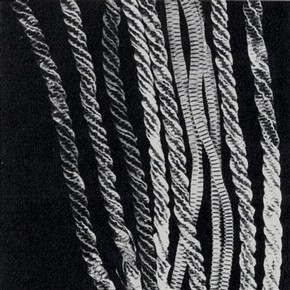

Fig. 1. 'Nishibiki himo' for ornamenting the hair, Inc 8 no. 67. Folded paper (kozo) (click image for larger version)

The Parkes Collection consists of 400 or so different specimens of paper and other artifacts amounting to approximately 2,500 sheets from 21 named prefectures in Japan. It was collected between the end of the Edo period (1605-1867) and the beginning of the Meiji period (1868-1911) and contains samples of almost all of the Japanese papers manufactured during that time. It was assembled by Sir Harry Smith Parkes, the British Consul in Japan, and shipped to England in March 1871 to be placed in the Education Department of the South Kensington Museum (later the V&A) on 6 September 1871 where it was stored in a number of Inclosures. A report on the manufacture of paper in Japan waspresented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. In 1874 some of the collection was transferred to the Royal Botanic Library at Kew.

The collection had rarely been seen until October 1993 when it was returned to Japan for research and display. It was exhibited at The Tobacco and Salt Museum in Tokyo and The Gifu Historical Museum in May and June 1994, and received around 30,000 visitors. It was the first time that the two parts of the collection, the paper samples preserved at the V&A and the examples of paper products kept in the Royal Botanic Library at Kew, had been reunited and shown together in the same exhibition.

Japanese papermaking

I have often been asked why this collection is important, so I will attempt to explain its significance in relation to the history of papermaking in Japan. The technique of papermaking originated in China and was introduced to Japan through Korea in the year 610. The Imperial Court encouraged the development of new and better techniques, the widespread cultivation of 'kozo' and the introduction of 'gampi', thus laying down the basis of Japanese papermaking.

Japanese paper ('washi') is made from the bast fibre of kozo ('Broussonetia kajinoko'), gampi ('Diplomopha sikokiana') and mitsumata ('Edgeworthia papyrifera'). Around the year 800, each region of Japan became known for the type of paper it produced. The first government mill was founded in Kyoto and brought together the best papermakers from the surrounding areas. Competition between the craftsmen led to improved techniques and the development of the 'nagashi-zuki' method. (seeNote 1) This process evolved into a craft adapted to forming a variety of highly specialised long-fibred, thin papers.

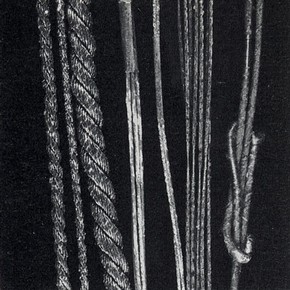

Fig. 2. 'Dai Kinnawa, Shô kinnawa', for ornamenting the hair. Inc 8 no 60. Sik and foil papers (kozo) (click image for larger version)

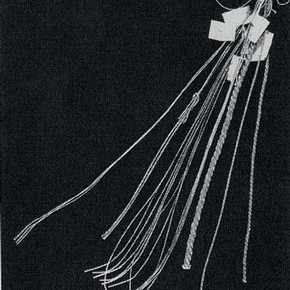

The Japanese have found their paper to be a vehicle for an entire range of human expression. It became one of the most indispensable materials of everyday life. Its strength and versatility enabled it to be used in a multitude of ways. It was rolled and twisted to form cord called 'koyori' and moulded or woven into shapes and lacquered to make boxes, hats and tobacco pouches. It was cut into fine strips and twisted into yarn and woven into cloth known as shifu. Other papers were treated with starch, oil, and persimmon and made into raincoats, umbrellas and lanterns. Special thin papers, evenly formed and translucent, were made for 'shoji' used as windows.

Others blocked with coloured designs, decorated with mica, ground-up mother-of-pearl, lacquer and gold were known as 'karakami' and used to decorate sliding panels that divide the room. As early as the 14th century, paper garments were made. Paper was treated with starch ('konniyaku') (see Note 2) and rubbed and wrinkled until it was soft and pliable. This paper was very strong: it retained the heat and kept out the wind and rain. Called 'kamico', it was first worn by Buddhist priests, as underwear and robes. It was used as clothing and bedding by the less well-off, because it was inexpensive, and was used for lining clothes until this century. It has recently undergone a revival and has been used for fashion garments. Ever since papermaking has been practised in Japan, plain white papers have been a symbol of purity and to the present day are used in Shinto worship.

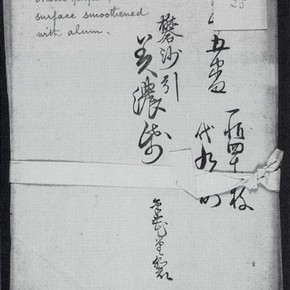

Fig. 3. Dosabiki Minogami, used for writing, K25 Kozo paper sized with alum. (click image for larger version)

Japan remained closed to the West until late in the history of Imperial explorations. Very little was known of the civilization and the unique place of the craft of papermaking in Japanese culture. The first comprehensive account of papermaking to reach the West was drawn from translations made from the diaries of Englebert Kaephler in 1712. In 1823 and again in 1854 Philippe Fray von Siebold visited Japan, returning with many examples of paper which are housed at the Dutch Ethnographical Museum. 1 Other smaller collections of plain, dyed and decorative papers can be found in museums and private collections, some resulting from papers brought over for the Second Great Exhibition in London in 1862, or later as gifts from the Japanese Government. Papermaking in Japan continued to thrive until the mid 1800s when Japan was forced to open her doors to trade and communications with the rest of the world and machine-made paper mills were set up. This increased contact with Western influences was to change many aspects of Japanese life irrevocably. Consequently the Parkes Collection of Japanese Papers contains examples of paper artifacts either unobtainable today, or of which very few samples survive. 'Washi became a victim of industrialisation and today has become an almost extinct craft'. 2

In 1872 Eiichi Shibusawa established the first Western-style paper industry in Japan, and it was at that time that the Right Hon. William Gladstone, Prime Minister of Britain, took an interest in 'washi' and the important role it played in the daily life and culture of Japan. His interest was possibly prompted by a report by Laurence Oliphant on Lord Elgin's visit to China and Japan between 1857 and 1859:

'We found... no less interest in examining the various uses to which they apply that most essential item in their wants - paper. It constituted the walls of our rooms and the fans that were in universal vogue - it was the wrapping of every purchase and furnished the string after which it tied.' 3 A request was made as early as 1865, on Gladstone's instructions, to furnish a report on the manufacture of articles of general domestic utility made from paper. However, at this time Japan was politically unstable, passing from feudalism under the Shogun to a modem Imperial state and, consequently, papermaking was not the most pressing issue. Gladstone reminded Clarendon, the Foreign Secretary, that the information had not been forthcoming from Japan and subsequently Parkes received a dispatch from Clarendon in May 1869.

Fig. 4. 'Dai Kinnawa,Shô kinnawa', for ornamenting the hair. Inc 8 no 60. (click image for larger version)

Harry Parkes headed the British diplomatic mission in Japan from 1865 to 1883. His personal adventures in the service of the British government are well documented but in the two volumes 'The Life of Sir Harry Parkes' 4 there is no mention of his involvement in assembling this remarkable collection of paper. It took two years to gather the 400 or so specimens of paper. Retained with the collection was a copy of the report made by Parkes and his three assistants, listing the districts of manufacture, cost and usage of the paper.

From the date it arrived in the Museum, 6 September 1871, until 1978, the collection lay undisturbed and was thought to be lost until it was rediscovered by Hans and Tanya Schmoller. They had travelled to Japan 2 years previously and had met the Director of the Paper Experimental Station at Ogowa in Saitama Prefecture, who showed a much-thumbed document which turned out to be a xerox copy of the Parkes report. The interpreter indicated it was a document greatly valued by the Japanese paper historians because it formed the only comprehensive record of the craft during the early Meiji period. On return from Japan they pursued the collection, visiting the V&A on numerous occasions. It could not be found in the Library or in the Prints and Drawings Department, and there was nothing known about such a collection.

In 1978 it was eventually located: it had been transferred to the Far Eastern Department in 1975 and had not been catalogued. Its discovery was reported in the 'Mainichi Daily News Tokyo' on 4 May 1978: 'Edo - Meiji: Japanese Hand-Made Papers Discovered in London Museum.' The newspaper suggested that the Parkes report had been carried out to ascertain whether or not fine quality papers being made in Japan could replace the so-called India papers used in making books such as bibles. 'At the V&A Museum the collection was packed into boxes such as those used for prints and drawings and stored in a remote corner of a printing room. The V&A people for the time being, fail to understand why there should be so much fuss about the collection, to them it is paper with nothing on it. This period was the zenith of Japanese hand-made paper.'

Recent history

I became interested in the collection after my first visit to Japan in 1984, when I had undertaken a study tour of papermaking areas around Tokyo and Kyoto.

In 1988, it was agreed by the Far Eastern Department that, in order to preserve the collection and at the same time make it more accessible to the public, each specimen needed to be identified and labelled, and rehoused in a suitable manner. This process took up my time within, but more often outside, Museum hours and in this way my fascination with, and knowledge of, the collection increased. At sporadic intervals I had the invaluable input of colleagues and visitors from Japan who provided a more intimate knowledge of Japanese papermaking.

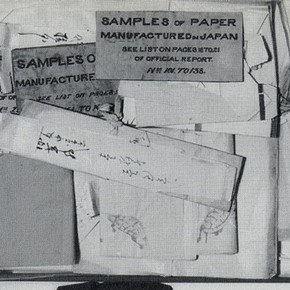

Fig. 5. Box of papers before cataloguing showing regional wrappers and hand-written labels. (click image for larger version)

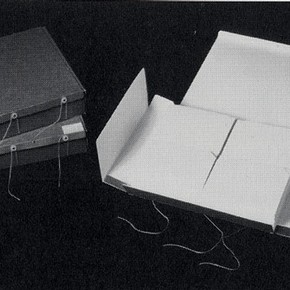

The overall condition of the collection was very good. However, several of the wall and screen papers from Inclosure 5 have at some time in their history been damaged by water, resulting in mould. Some of the plain papers from Inclosure 9 are foxed and badly creased or soiled through lack of protection. The papers are now stored in six boxes measttring 560 x 460 x 460mm, made from 130µm archival folding box board (Atlantis Paper Co.) lined with 5mm Plastazote on the base (Wilford Polyforms). Individual sheets of paper and labelled packets of paper are housed in envelopes of 315g wood-free Heritage paper in three sizes (Atlantis). 5

In 1992 each sheet was numbered and put on the Museum's computerised location system by Anna Jackson (curator in the Far Eastern Department). The value of the collection in its detail and its breadth provides a fascinating insight not only into the ingenuity with which the Japanese used paper but also into the mores of early Meiji Japan. Poetry paper, hair ornaments, envelopes, hats, umbrellas, raincoats, all made from paper, enhance our appreciation of what was popular and fashionable at that specific time.

Exhibition in Japan

Fig. 6. Papers after cataloguing showing how they are now stored at the V&A. (click image for larger version)

It was always hoped that this collection would one day be exhibited in Japan. This possibility became a reality in 1991, when the Director of the Paper Museum in Tokyo, Shiichi Hasegawa, made a brief visit to see the collection and decided that he would make it happen. After much discussion and visits from paper historians in Japan, the Museum received a formal request and it was agreed that the collection would be exhibited in the spring of 1994. Part of that agreement was that it would be sent out six months in advance, in order that research could be carried out and the catalogue prepared.

I was given the opportunity to courier the collection. This enabled me to meet colleagues from the Paper Museum who were involved in the project and to discuss the research to be undertaken. This would centre around the comparison of the Parkes papers with those of contemporary papers made by traditional methods. I was also able to see the exhibition area at the Tobacco and Salt Museum in Tokyo and to discuss such matters as handling, display, light levels and security, and to iron out any problems regarding the catalogue and postcards.

Research

The research was undertaken by Hidetoshi Komiya from the Paper Museum in Tokyo, assisted by Kumi Igarashi.

One hundred and sixty papers were examined for size, weight, thickness, and density using TAPPI (Technical Association of Pulp and Paper Industry) standards. Laid and chain lines were measured. Fibres were confirmed using microscopic analysis. The fibres were found to be kozo, gampi and mitsumata. Of the papers examined there were no examples where more than one fibre type had been used. It was also found that only 27 of the paper sheets examined had been formed on bamboo moulds. The others had been formed on reed moulds.

The examination of the papers will continue and Dr Inaba from the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music will carry out the research.

In May 1994 I travelled to Tokyo to oversee the installation of the collection for display at the Tobacco and Salt Museum. The collection was exhibited in a gallery designated for international exhibitions, with a display area of approximately 1,007m2. The major part of the exhibition was drawn from the Parkes Collection with additional material from the Paper Museum and the Tobacco and Salt Museum. The exhibition was divided into approximately 12 sections outlining the history of paper, its manufacture, its treatment, its decoration and its use. Most of the material was displayed in cases, except for some samples of modern papers that had been exhibited in order to encourage the public to look and feel the different qualities, texture and weight of the various papers. Other material was used to illustrate the manufacture of paper, such as a series of photographs that had been made from woodblock prints illustrating the 'Kamisuki Chohoki (A Handy Guide to Papermaking 1798)'. 6 Woodblock prints were used to, illustrate the manufacture of leather papers; also exhibited were the carved wooden rollers used for embossing the papers such as those from Kew. Exhibits also included a kimono made from 'kamiko', a 'tabashi' lined with 'chyogami' - a colourful block-printed and stencilled paper.

One of my favourite objects was a belt used for carrying medicines; each sample was contained in tiny folded packets made from a 'gampi' paper called 'yakutaishi', or drug bag paper. The Parkes Collection has many samples of this paper. Some papers have been coated with a protective dye containing persimmon, a waterproofing agent; others have been treated with iron oxide. There were papers for writing and printing, poetry, letters, notebooks, papers for book covers, dyed papers, recycled papers, wrapping and bag papers and papers for ornamenting the hair. Included in the exhibition were a selection of papers from the Rutherford Alcock collection of 'fusuma' paper. These papers are from a sample book, and would have been specially commissioned from 'karakami' papermakers of this period. It was thought that these papers would make a pertinent and welcome supplement to the exhibition. Not only was Rutherford Alcock Parkes' predecessor in the role of British Consul to Japan, he was also responsible for assembling the collection of objects from the 1862 International Exhibition, a key event in the rise of British interest in Japanese art and design. The exhibition in Tokyo was opened by the British Ambassador, Sir John Boyd and Jiro Kawake, Chairman of the Japan Paper Association.

Today the Japan Paper Industry is the second largest in the world. During this time the production of 'washi' has decreased but its excellent qualities have been maintained by the use of traditional skills. In 1968 two 'washi'-makers were designated Important Intangible Culture Assets and so conservation of traditional techniques in papermaking were recognised. Since 1975 'washi' has again become appreciated and the government is actively promoting it as a Traditional Industrial Art.

'Handmade paper is indeed a humble substance, but then are not beauty and humility all the more reason to pay an object homage?' 7

References

1. Schmoller, H. 'Mr Gladstone's Washi'. Bird and Bull Press, Newtown, Pennsylvania, 1984, pp.3-4.

2. Gerd, L. Washi - Japan's Handmade Paper and its Myriad Uses, 'Arts of Asia', Feb. 1995, p.76.

3. Oliphant, L. 'Narrative of the Earl of Elgin's mission to China and Japan, Vol II', Edinburgh & London, 1859, pp.185-6.

4. Lane-Poole, S. & Dickens, F.V. 'The Life of Harry Parkes, Vols 1 &2', London,1894.

5. Webber P. Thomson A. 'An Introduction to the Parkes Collection of Japanese Papers', 'The Paper Conservator', 1991, Volume 15, p.8.

6. Kunisaki, J. 'Kamisuki Chohoki', illustrated by Seichuan Niwa Tokei, Pup Osaka, 1798.

7. Hughes S. 'Washi - The World of Japanese Paper', Kondansha Int. Tokyo 1978, p. 37.

Notes

April 1995 Issue 15

- Editorial

- The Parkes collection of Japanese paper

- Restoration - is it acceptable?: review of the conference held at the British Museum 24-25 November, 1994

- To play or not to play: the ethics of musical instrument conservation

- The conservation and rehousing of a collection of photographs and photomechanical prints

- Book review: locked in the laboratory

- Conservation course abstracts: update