Conservation Journal

April 1995 Issue 15

To play or not to play: the ethics of musical instrument conservation

Fig 1. The Horniman Museum Musical Instrument Collection, about 1904. Reproduced with permission from The Horniman Museum, London. (click image for larger version)

The music collections held by museums in the UK are varied in scope and character. The larger collections were generally begun by enthusiasts whose common purpose was to preserve historic instruments. They tend to include instruments covering a wide geographical and historical range. The more outstanding collections were built up in the nineteenth century and have since been acquired by museums and educational institutions. (Fig.1) They have developed in response to changing musical tastes and interests and each collection represents a combination of original purpose and subsequent acquisition policy. In addition to the specialised and more comprehensive collections, many museums hold musical objects among their collections, a sign of the importance and universality of musical experience in our society.

As a species of museum object, musical instruments can provide the curator and conservator with some dilemmas. Musical instruments are designed to be functional objects. They have moving parts or they require physical interaction to fulfil the purpose for which they were made. They have this in common with many other objects including clocks, transport vehicles, arms and armour, hand tools, domestic utensils, scientific apparatus and industrial machinery. The role of such objects in collections is generally to document historical change - to illustrate a point about our environment, society, culture, technology or other facets of the world in which we live. In common with many of these objects, musical instruments cannot be fully appreciated or understood only in terms of their appearance, materials and construction. The primary function of an instrument is usually to produce sound. If we are not permitted to hear the music it makes, our experience of an instrument is limited and its role as a historical document can only be partially fulfilled. This introduces the question: if an instrument is in a collection why should it not be played?

In 1967, ICOM published a document entitled 'Preservation and Restoration of Musical Instruments' and there have been several publications of importance since (seeBibliography ). This sought to lay guidelines for treating musical objects in public collections. It paid great respect to both the tonal and decorative qualities of historical musical instruments. It also discouraged the outright modernisation of old instruments, a practice which had previously been very common. Since 1967, there has indeed been ethical progress and it is widely recognised that the materials and techniques found in old objects are no longer disposable. We cannot simply remove unserviceable parts without understanding that we may be also removing important evidence such as original tool marks, patterns of use or patination.

As conservators, we can reasonably claim that an ethical code for dealing with the objects before us should include the following points:

1.The aesthetic, historic and physical integrity of the object should be respected.

2.Decisions on the extent of treatment should not be influenced too greatly on the subjective grounds of quality or value.

3.Where possible, techniques should be avoided where the results cannot be undone if that should become desirable.

4.Restoration should proceed according to a firm previous understanding with the owner or custodian but without modifying the known character of the original.

Conservation practice requires such an ethical basis in order that sound decisions might be made. Musical instruments, however, provide a neat paradox which can confound this process. The integrity of an instrument surely includes its sound and yet it is realised that to use an instrument is an inherently destructive process. In order to bring an instrument into playable condition, it may be necessary to 'modify the original' and in ways that are not readily undone. The question of whether musical instruments are to be played is hence a source of much emotive debate, compounded by the fact that many old instruments, of the greatest quality, are still being used by performers.

There are a number of reasons why musical instruments held in public collections might be played. Whether they are or not will depend on the philosophy of a museum and in particular its idea of whom it should serve. A strong argument for the playing of historical instruments is that usage was a condition for their inclusion in public collections in the first place. Some of the large nineteenth century collections started life as musical instrument libraries. Other collections are attached to educational institutions for the sole purpose of providing access to the instruments for a community of musical scholars. It is now being recognized, however, that such institutions have a broader responsibility to the community at large and policies may have to be reconsidered.(Fig.2) A factor which may resolve some of these issues is that many aspects of music and sound lend themselves readily to modern, interactive methods of display.

One serious argument in favour of playing historical instruments is that certain music cannot be appreciated properly without them. The general idea is that period music should be played on the instruments for which it was written. One alternative - transposition for modern instruments - is considered to be an approach which can compromise the original composition. Another possibility is to copy 'authentic' instruments, but more of this below. The revival of 'Early Music' has certainly created a demand for early musical instruments. This, in turn, has created a demand for information and evidence from which to make reconstructions. It is not always enough, however, to have seen the original instrument in order to create a reproductiop or reconstruction. Further study might be needed, of documents or drawings and other instruments by the same maker or of the same period. One of the responsibilities of a museum holding a collection of instruments is to provide this kind of information.

Even with accurate information, there is widespread doubt about the success and musicological validity of the copying process. It is becoming accepted that it is difficult to reproduce accurately and authentically the sound of one instrument by any other. If this were not the case then every violin maker would be producing Stradivarius copies. There are a number of reasons for this, the main one being the complexity of the acoustic model which characterises each instrument. This is the sum total of all the influences on sound production.

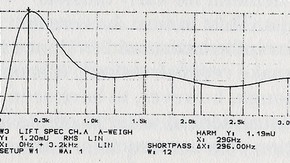

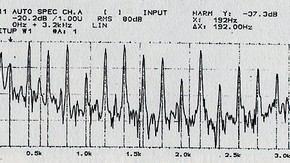

It begins with the musician who imposes their own stamp on the sound. The player develops, over a period of time, a subconscious feedback mechanism by which they become used to and learn to control all the nuances of the instrument. The shape of the instrument determines which harmonics will be most dominant. A second pattern, from the method of amplification, will overlay the amplitude pattern of the harmonics to provide a spectrum of sound which is unique for every instrument (Fig. 3a). This spectrum can be analysed and represented graphically in a sound 'envelope' which is called a formant.(Fig. 3b)

Fig 4. A Lute made by Arnold Dolmetsch, 1893. Reproduced with permission from The Horniman Museum, London. (click image for larger version)

The materials from which the instrument is made, including glues and varnishes, are crucial to the formant. Modern instrument makers are not able to reproduce the shape and materials of historical instruments precisely but they can come very close, using carefully observed historical evidence. (Fig.4) There are, however, other influences on the shape of the formant when the instrument is used, beyond the shape and materials of the instrument and the action of the musician. These include the place where the instrument is played (room acoustic) and the person who is listening to the instrument (ear).

Besides the difficulty of reproducing an authentic sound, there is another factor to consider. Unfortunately most instruments do not improve with age and historic instruments no longer sound as they originally did. Many types of instruments have a very limited life span. Woodwinds are generally not expected to be fully functional for much longer than 20 years. Brass instruments suffer from stress cracking owing to production methods and heavy treatment which puts their lifespan into a similar category. Pianos are expected to last about 100 years while most string instruments can go on for a maximum of 200 years. In any event, all instruments have a finite life expectancy and, once beyond this, they cannot be brought back to life with any expectation of maintaining the original sound quality. It is distinctly possible that a good copy may be closer to the 'original' sound than the historical instrument itself!

Fig 5. Margaret Birley and Herbert Heyde measuring a Moroccan Nfir. 1993. Photography by SRH Spicer, The Shrine To Music Museum, University of South Dakota. Reproduced with permission. (click image for larger version)

There are a number of methods for prolonging the active life of instruments but these all require the replacement of original parts. This is a material modification which will alter the sound quality and the formant. This is an area of music technology which gives scope for some interesting technical research. Most instruments undergo a series of modifications during the course of their lifetimes which will include the replacement of broken strings, reeds or other delicate parts. Pianos require frequent tuning and regulation which can include replacement of strings and felts. Woodwinds often need key re-padding and re-springing. Some instrument technologists make their living by only doing very specific types of these jobs, for example, modifying keywork for orchestral clarinets. Violins are particularly prone to this kind of treatment to the extent that over 75% of the instrument can be replaced yet the instrument will still keep its market value. It is very rarely an instrument will come into a public collection still in its original condition.(Fig 5)

It has been recommended that instruments from public collections should not be allowed to be played where the motive is idle curiosity or individual pleasure. There is a clear risk of mechanical damage if any instrument is to be used. Tuning a string instrument will cause stress and the introduction of moist air into a wind instrument may be more than it can withstand. However, there are occasions where a justification can be made for an instrument to be played. Naturally, it is recommended that this be done under close supervision and that players are not permitted to make adjustments of any kind. But there are questions which have yet to be approached.

If an instrument in a museum collection is to be played, who has the right to play it? By being in a museum, instruments acquire an aura of importance, and in the past their use has been the prerogative of musical specialists and experts. Such limited access does not provide enjoyment for or meet the needs of the public, so there is a school of thought which suggests that, if an instrument is to be played, then it must be for the widest possible audience. This can be achieved by special concert performances or sound recordings.

However, recording is not without its difficulties: the best digital sampling techniques will still capture an incomplete harmonic record of the sound.

There is thus a wide range of possibilities for the use of musical instruments in museum collections. At one extreme, there are instruments which are freely lent to players for performances or practice. At the other, there are those which are never played at all and for which any information on the sound they make comes from observation, measurement and non-destructive testing. These polarised approaches to the use and preservation of musical instruments in collections are both valid in different circumstances. They must be controlled and conditioned by a careful assessment of the resource on an institutional and on a broader basis. On the one hand, it is surely acceptable to allow limited playing of certain chosen instruments without seriously compromising the overall obligation for museums to preserve. Without such opportunities, much of value in musical experience, education and research is lost. On the other, it must never be forgotten that these objects constitute a non-renewable cultural resource. If the wish to preserve becomes very much secondary to the wish to perform, then the resource will be lost.

Bibliography

International Council of Museums. 'Preservation and Restoration of Musical Instruments', 1967, ICOM.

International Committee of Musical Instrument Museums & Collections (CIMCIM). 'Recommendations for Regulating the Access to Musical Instruments in Public Collections', 1985, ICOM.

International Committee of Musical Instrument Museums & Collections (CIMCIM). 'Copies of Historic Musical Instruments', 1994, CIMCIM.

Galpin, Francis W. 'Old English Instruments of Music', 1910, Methuen.

Arnold Forster, Kate and La Rue, Helene. 'Museums of Music', 1993, HMSO.

Museum and Galleries Commission. 'Standards in the Museum Care of Musical Instruments', 1995.

Footnote

This article is the text for a paper given at the Conservation Student Conference in Lincoln in March 1995. Archetype Publications are compiling the synopses of all the presentations at the conference. Anyone wishing to obtain a set should contact Archetype directly.

April 1995 Issue 15

- Editorial

- The Parkes collection of Japanese paper

- Restoration - is it acceptable?: review of the conference held at the British Museum 24-25 November, 1994

- To play or not to play: the ethics of musical instrument conservation

- The conservation and rehousing of a collection of photographs and photomechanical prints

- Book review: locked in the laboratory

- Conservation course abstracts: update