Conservation Journal

July 1995 Issue 16

Those Who Can...

The RCA/V&A Conservation Course contribution to the Journal usually concentrates on the activities of the students, and rightly so. This time, however, the focus is on the teachers.

It is a well-worn adage that 'Those who can, do; those who cannot, teach'. Experience tends to confirm that experts in a particular field do not necessarily make the best teachers. This article discusses the ethos of the RCA/V&A Conservation Course (not exclusive to this course) that the best teachers of conservation need to be experts in their field and that a good starting point is to take people who not only can, but do. Some of the ways in which teaching standards are monitored and developed in the V&A Conservation Department are described and set in the wider context of conservation training. These are issues which have been discussed at recent meetings of the ICOM-Conservation Committee Training Working Group (ICOMCC TWG) in Maastricht and of the UK's national group, the Conservation Teachers' Forum (CTF) (see footnote ).

The main theme of the Maastricht meeting in April 1995 was standards and comparability of conservation education and qualifications. Within this, the question of the teachers' or trainers' own standards and qualifications was raised, specifically by Colin Pearson who re-presented his 'Code of Practice for Conservation Education and Training', first given at the ICOMCC Triennial Meeting in Washington DC in 19931 . Since then only two responses had been received, which Colin charitably put down to pressure of work and gave the Working Group another chance to consider whether such a document was worth pursuing. The consensus was that the document needed modification but was a worthwhile contribution to the field. The re-drafting of the 'Code of Practice', amended to the status of 'Guidelines', became the subject of a meeting of the UK's national group, the Conservation Teachers' Forum (CTF), in May 1995.

Another thread running through the ICOM-CC TWG meeting was the importance, indeed the absolute necessity, of practical oexperience in the workplace as part of a conservator's professional education. More and more courses are being established worldwide with periods of work experience as a compulsory element. Not only are there more courses, and therefore more students seeking placements, but more is being asked of such placements. Both Annette Kipp of the Opleiding Restauratoren in Amsterdam and Anne Bacon of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle described their expectations of workplace-based training which went far beyond the opportunity merely to work alongside professional conservators, observing and absorbing good practice. To get the maximum benefit such placements must be structured, be integrated into the academic programme and be assessed or accredited. This is, of course, entirely laudable, but is it realistic? Anne Bacon called for much better integration between teaching institutions and the profession but, in the UK public sector at least, the profession is under increasing pressure to produce conserved objects for displays and loans and to account for resources in a heretofore unprecedented way.

If practising conservators are to become even more fully involved in training in a mutually rewarding way, the case for accepting time-consuming students must be carefully argued at all levels within the conservation profession and beyond it. Training of new entrants should be seen as part of a professional conservator's responsibilities. It is mentioned in several of the codes of conduct, but this must be recognised and valued by institutions and employers; it will not work well if training is somehow to be fitted in with all the other duties of a professional conservator in an institution or in private practice. It was interesting that the appraisal system and promotion criteria of the British Museum Conservation Department, described by its Keeper, Andrew Oddy, made very scant mention of training others as a way of 'scoring points', despite the fact that the Department is active in accepting interns. Alan Cummings, Director of the RCA/V&A Conservation Course, summarised this need to develop a culture of training and education as a call for major institutions to see themselves as 'teaching museums' analogous to teaching hospitals in the much-analogised profession of medicine.

CTF is an informal group of those actively involved in conservation teaching. Meetings are advertised and reported in UKIC publications Conservation News and Grapevine.

The V&A Conservation Department is quite a long way down this road already. Having our own full-time students on the RCAfV&A Conservation Course and hosting many internships and placements from other courses worldwide means that we are in a position to see the points of view of both the teaching institution and the working museum. Once a studentship has been agreed, the problem of providing real work experience does not, fortunately, arise for the RCA/V&A Conservation Course since the MA students are firmly based in working studios at the V&A or elsewhere. However, short placements in other institutions occur regularly, and are much appreciated by students and staff, since we know just how much work goes into studentships, internships and placements if they are to be taken seriously and be beneficial to all parties. An earlier Journal article discussed the establishment of a policy covering all of these activities2 , which are taken into account when recruiting and appraising staff and in all the Department's forward planning.

However, this is not to say that running a teaching programme in an institution which is not primarily set up for that purpose does not have its own problems. One of these, which is frequently voiced by the senior conservators appointed to supervise the MA students' practical studio work, is that they themselves have generally received no training as trainers and cannot be certain that they are doing it 'right'. The fact is that it is doubtful whether any of the V&A supervisors have been through formal teacher training, so what makes them qualified to teach conservation to others? As stated at the beginning of this article, it is primarily the fact that they are each among the foremost practitioners in their field; there is no doubt that they can. The question remains of how well they teach. It would be unrealistic to expect all conservators to enjoy or to be good at teaching to the same degree. In this, as in many other aspects of the Course, direct comparison is neither possible nor useful. Resources, studio practices and the students themselves vary enormously. Provided that a minimum standard is reached across a range of activities, and excellence is achieved in at least some, such diversity is acceptable.

It is our aim, however, to raise the overall standard of studio teaching. Practical supervisors should feel that they are gaining new or improved skills by accepting students and that their achievements in this regard are valued. The intention is also to try to foster a sense of community among teachers within the Department, as most supervisors work in some isolation in their own studios. Many staff already have their own links with the broader sphere of conservation education and training through acting as external examiners, advisers or lecturers and through accepting interns, but it also a major function of the Course Director and Tutor to maintain and augment these links.

At a basic level, it is intended to bring together all the practical supervisors at least once per term so that experiences can be shared and problems aired. When we have managed to meet, it has proved very useful - for instance, a minimum tutorial time for all students was recently agreed - but the constant problem is the pressure of other demands on staff time. It is also profitable to look beyond the Course. In February the Department hosted a one-day workshop on training in the workplace at which invited speakers discussed their approaches to and organisation of practical teaching. These were Janey Cronyn (consultant to the Museum Training Institute), Frankie Halahan (City & Guilds of London Art School), Agnes Holden (in her role as Secretary to the British Society of Master Glass Painters), Rob Payton (Museum of London), Anna Southall (Tate Gallery) and Sue Thomas (De Montfort University, Lincoln). The topics covered included formal training courses, internships, in-service accreditation and National Vocational Qualifications.

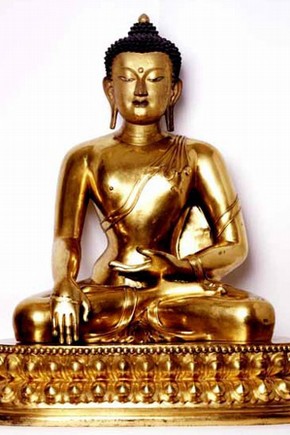

Conservation of gilded copper alloy statue of Buddha. Museum no. IM 227 1920 (click image for larger version)

Such events provide a forum for discussion of issues; there is also demand for specific training of staff in techniques of training. The fact that this arises from the staff themselves demonstrates their commitment to improving their skills. To this end a 'Training for Trainers' course lasting one and a half days has been developed by the V&A's in-house Training Section. It was hoped that the first course would have been run in May 1995, but it is now scheduled for September: it is all very well having the commitment, but finding the time in a hectic schedule is the chronic problem.

The V&A, or other collaborating institution, is only one partner in the Course. The academic staff of the Royal College of Art and Imperial College who, while not expected to have a deep understanding of conservation, contribute their experience with large numbers of students as well as their specialist expertise. Both Colleges offer training for their own staff which the Conservation Course staff could tap into, either via the Director/Tutor or directly.

Looking further afield, there was a suggestion at Maastricht that ICCROM could and should be encouraged to re-run its programme of training for conservation trainers. Past participants reported that it had been extremely useful and those interested should write to ICCROM to support revival of the course. Perhaps it could be run in the UK, even at the V&A, though we are not making any promises! So, how do we know whether we are doing it right? There are numerous evaluation, appraisal and validation exercises which the Course goes through. These are of varying frequency and complexity, ranging from comment sheets for individual seminars to five-yearly Re-Validation, and involve both internal and external review. There is not room to discuss them here. Regarding outcomes (i.e. graduate students), it is still too early to draw firm conclusions: only 17 students have graduated since the Course's inception in 1989. We are, however, generally highly satisfied with their record in terms of work produced during their studentships and in their subsequent careers. It is by them that the Course will come to be judged by the profession. We intend that our students should have the best education by providing access to conservators who not only can and do, but can teach as well.

Footnote

CTF is an informal group of those actively involved in conservation teaching. Meetings are advertised and reported in UKIC publications 'Conservation News' and 'Grapevine'.

References

1. Pearson, C. and Ferguson, R. 'Code of Practice for Conservation Education and Training' in Preprints of the 10th Trienniial Meeting, Washington DC, USA, 22-27 August 1993, ICOM Committee for Conservation, pp.731-737.

2. Cummings, A. 'The Training and Research Group', 'V&A Conservation Journal' October 1994, No. 13, pp. 11-13. Copies of the policy document available on request.