Conservation Journal

January 1996 Issue 18

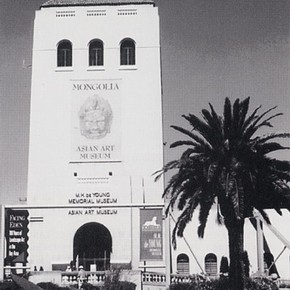

Summer Placement at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco was founded by Avery Brundage, a dedicated collector of Asian art. He left his collection of some 10,000 objects to the city of San Francisco on the condition that the city build a museum to house it. This museum opened in 1966 and it was in its Conservation Department that I undertook an eight week internship between July and September 1995.

Apart from the Head of the Department, Linda Scheifler Marks, the Conservation Department employs a textile conservator, a paper conservator and an objects conservator. For special projects the staff is augmented by contracted conservators. This summer they also had two interns: myself and a student from the University of Delaware conservation programme.

On our first day we were given a tour of the storage areas. A museum in a major earthquake zone has to take special precautions and these were explained to us by Linda Scheifler Marks. All the storage cabinets were bolted to the floor and all the objects within the cabinets were surrounded by sausage-shaped sandbags. The objects on display were also securely anchored down with either microcrystalline wax, sandbags, fishing line or bolts. The use of microcrystalline wax was of particular interest to me as it could be used to prevent ceramic and glass objects 'creeping' along shelves, a problem sometimes encountered in the V&A in galleries with springy floors such as the 20th Century Gallery. The Asian Art Museum's precautions were tested on 17 October, 1989 when the earthquake Loma Prieta struck. Remarkably only three objects were broken, all of which were ceramic and all of which I repaired during my internship.

To someone unused to living with the threat of an earthquake some actions, such as leaving a sliding cupboard door open, seem harmless but in a 'quake the falling objects would add needless hazards to the situation. Every new member of staff is also shown the location of the emergency bag for their department which contains essentials such as a torch. Thankfully this was not required during my internship.

My major projects whilst at the museum were the aforementioned earthquake-damaged ceramics. These consisted of a 3000-2000 B.C. Japanese Jormon Jar and two eighteenth century pieces of Chinese porcelain. The Jormon Jar was made of very low fired earthenware which had been repaired previously. During the earthquake, a section of the rim had broken off and several cracks had appeared down its body. As the lower section of the jar was stable it was decided to dismantle the top section only and then reassemble it using Paraloid B72 TM(Rohm Haas), ethyl methacrylate/methyl acrylate copolymer, in acetone. The missing areas were filled with Patch-N-Paint Lightweight Vinyl Spackling TM (Custom Building Products), tinted with dry ground pigments. I became a great fan of this filling material as it did not shrink or change colour, when tinted, on drying (unlike some British products).

During the eight weeks I was given the opportunity to visit the laboratory where object analysis is carried out for the museum. Surface Science Laboratories in Mountain View offer a vast range of analytical techniques. The purpose of our visit was to get scanning electron microscopy (SEM) performed on samples from a light degraded lacquer table.

The laboratory had previously conducted gas chromatography/ mass spectrometry (GC/MS), fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and SEM with energy dispersive X-ray analysis (SEM/EDX) on material from a display case. A liquid had entered the case via an old drainpipe and stained not only the case but the base of a 12th-13th century Iranian Vase in the case. The outcome of the analysis was that the stain was the diluted residue of a sugar-containing drink but one which did not contain caffeine, so regular cola could be ruled out! Armed with this information I removed the stain from the ceramic using swabs of saliva and deionised water.

My internship coincided with the opening of a major new exhibition at the museum, 'Mongolia. The legacy of Chinggis Khan'. The visitor numbers increased markedly in this period and consequently the environmental conditions in the galleries were affected. This could be seen on the thermohygrograph charts, which were changed weekly. Using these charts, the Buildings Department could be notified to take appropriate compensatory measures. 'Watering the art' was another environmental measure I was involved in. This alarming term refers to the topping up of the humidifiers in the galleries, to ensure 'the art' does not become too dry and hence damaged.

Whilst at the museum I examined and completed condition reports on ceramics which were going out as two loans in the near future. One loan was destined for the soon-to-be-reopened Palace of the Legion of Honour in San Francisco and the other was a touring exhibition of Korean ceramics. I

also conducted a condition survey of the museum's collection of Chinese glass.

A label removal project was already underway on the Chinese ceramic collection when I arrived. I continued this project to the Near Eastern ceramic collection. All the ceramics were photographed before and after the labels or label residue was removed. I also had time to treat a 12th-13th century Persian, highfired earthenware bowl whose old restoration was severely discoloured.

I also had the opportunity to visit the Oakland Museum and its Conservation Department and that of the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco.

I would like to thank everyone at the Asian Art Museum for making my time so enjoyable, especially the Conservation Department: Linda Scheifler Marks, Tracy Power, Teresa Heady, Julie Goldman and Kathy Gillis.

January 1996 Issue 18

- Editorial

- The Examination and Conservation of the Raphael Cartoons: an interim report

- Tarnishing of Silver: A Short Review

- The Xmas Cake Dress

- Review: Lining and Backing - The Support of Paintings, Paper and Textiles

- Student Summer Placements

- Summer Placement at the Canadian Museum of Civilisation

- Summer Placement at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Summer Placement at the Metropolitan Museum of Art