Conservation Journal

January 1996 Issue 18

Summer Placement at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

On my arrival at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA), I was welcomed by Antoine Wilmering, Head of the Furniture Section and Conservator of Objects Conservation. He took me to the Sherman Fairchild Centre for Objects Conservation, where I was introduced to all the members of staff. Soon I was given a work area close to Henning Schulze, a young German conservator, who would be my supervisor during my internship.

A couple of hours after I arrived I was invited to join the other furniture conservators in the section to see a newly opened furniture exhibition called The Herter Brothers, Furniture and Interiors for a Gilded Age. This was the first day a group of furniture conservators and curators from the MMA, together with three curators from other museums involved in the Herter Brothers Exhibition, met to discuss the construction, decoration, conservation treatment and display of the furniture. We spent a whole morning together and met again on the three following Mondays. I found this a very useful experience even though I had no prior knowledge about the Herter Brothers and the period they represent in the development and history of American Furniture and interior design.

During my internship I worked on two objects: a German carved, painted and gilded centre table from the turn of the century and a fifteenth century Italian credenza. The table was going back to the castle it originally came from on long term loan and had to be ready for packing for subsequent shipping two weeks after it was brought to the conservation studio. The Italian credenza was in need of more extensive treatment. This took up the rest of my time in the section.

The German table was made in the late 19th or early 20th century but with 18th century carvings. It is part of a larger suite of furniture identified as having been in the garden room of the Franckenstein Pavilion at Schloss Seehof, near Bamberg, Germany. It is believed that a pair of wall brackets and tops from this group of furniture were used for the construction of this centre table at the turn of the century. In 1956, the suite of furniture, as well as the table, were offered by the Von Hesselberg family, Seehof's last private owners, to a Munich dealer. The dealer, Fisher-Bohler, sold this furniture in the same year to Mrs. Emma Sheafer for use in her New York apartment.

The furniture is primarily made of lime although the table has an oak top and the carved (lime) frieze is painted and gilded. Lime is more often found in sculpture than furniture of the period. The choice of material and manner of construction, together with the free and unique design of the pieces, suggest that the suite may have originated from the workshop of a carver or sculptor rather than that of a cabinetmaker. All the elements of the polychrome decoration and the glaze had previously been identified through energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis by Mark Wypyski, Department of Objects Conservation, MMA. The flowers of the apron, rail and frame have a coating of lead white, on top of which the paint layers of the leaves and petals in pigments, common to the period, were applied. Originally a green glaze was applied all over the gilding.

Before treatment, signs of deterioration included splits in the legs, lost and flaking gesso, loose legs, a sagging frieze and a scratched table top. Treatment involved securing the structure, closing the splits, consolidating flaking gesso and paint, surface cleaning and retouching.

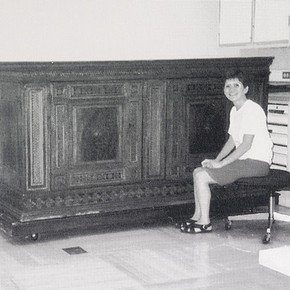

The Italian credenza had been in store ever since it was acquired by the museum in 1945 and was in need of extensive conservation. The surface had accumulated so much dirt over the years that it was difficult to read the geometric patterns of the intarsia. The inlay decorating the front and sides was loose and partially missing.

This object gave me the opportunity to undertake some microscopic analysis. Nine samples of the surface were taken to detect whether there had been any painted decoration. The samples were embedded in a liquid synthetic resin. The next day the small resin cubes were sawn, ground and polished with wet-or-dry paper and finished off with very fine emery cloth. Viewed through the microscope the samples showed no signs of polychrome decoration nor a distinct layer structure of other finishes. What we saw were simply different degrees of accumulated dirt.

In discussion with my colleagues about the best approach to cleaning the object, I was advised to first test with a very gentle cleaning agent. Much of the dirt came off, but still there was not enough contrast between the different coloured woods to make the inlay easy to read. Following more discussion and testing, it was decided that further cleaning using stronger, more polar solvents was needed. The next step was to use industrial methylated spirits, water and saliva. To even out any differences in tone and colour which occurred during cleaning, a few areas were retouched lightly with fine artist's water colours. To saturate the surface and enhance the colours of the various inlaid woods the credenza was then lightly waxed with beeswax that had been diluted with turpentine.

This practical work in the studio took up most of my time at the museum, but I was free to attend seminars and gallery talks and take part in other activities of interest throughout my internship. I took full advantage of this and attended a number of seminars on furniture and decorative arts history by MMA staff and others.

I thoroughly enjoyed my summer internship in the furniture section and found it a very useful and refreshing experience. I would like to thank all the conservators in the section for their advice, help and encouragement during my stay.

January 1996 Issue 18

- Editorial

- The Examination and Conservation of the Raphael Cartoons: an interim report

- Tarnishing of Silver: A Short Review

- The Xmas Cake Dress

- Review: Lining and Backing - The Support of Paintings, Paper and Textiles

- Student Summer Placements

- Summer Placement at the Canadian Museum of Civilisation

- Summer Placement at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Summer Placement at the Metropolitan Museum of Art