Conservation Journal

July 1997 Issue 24

The Conservation of Nineteenth Century Dissected Puzzles

This project was carried out as the final part of an MA in Paper Conservation at Camberwell College of Arts. It was completed in November 1996, shortly before I began working at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Jigsaws are popular with both institutional and private collectors yet little work had previously been completed concerning their preservation and care. The purpose of the project was to examine the problems associated with this type of composite object and to provide an initial framework for their conservation.

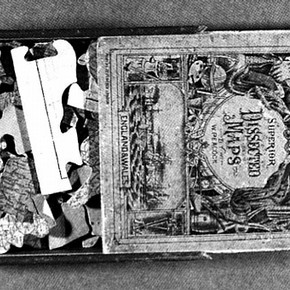

Dissected puzzles, or jigsaws as they came to be known after 1870, originated in eighteenth century England and quickly became very popular toys. The earliest puzzles were high quality items; however changes in the nineteenth century involved the use of poorer materials and the puzzles tend to have deteriorated to a great extent. Wooden pieces were phased out in the twentieth century and so this project focused on nineteenth century puzzles, of which numerous examples survive. The jigsaws usually comprise of wooden puzzle pieces onto which hand coloured prints on paper were adhered. They were housed in wooden boxes of sliding lid construction with a varnished image glued to the lid (Figure 1). Often paper 'key pictures' were also included to serve as a guide to the completed puzzle.

Survey and Condition

Figure 1. View of partially opened box showing an 1870 map jigsaw puzzle of England and Wales (click image for larger version)

Initially a survey was developed to determine the extent and nature of deterioration patterns to the puzzles. This was carried out on the nineteenth century jigsaw collection at the National Museum of Childhood, Bethnal Green (NMC). The survey results revealed the forms of typical damage, and was accompanied by information gained from the Benevolent Society of Dissectologists, a group of jigsaw puzzle enthusiasts. Damage originates from two main areas - the nature of the materials used and the function of the puzzles as children's toys - and included warping of the wood, discoloured and deteriorated paper, cracked and yellowed varnish, abrasion, losses of entire pieces as well as parts, considerable surface dirt, accretions, previous repairs and biological damage.

Four puzzles were individually worked on, to illustrate how their conservation could be approached. One of these came from NMC and the others from the Jill Grey Collection in Hitchin, Hertfordshire. The jigsaws ranged in date and varied in size and quality, all displaying different problems. The NMC puzzle (1855) was double-sided and still had its key pictures. It had been repaired previously with pressure sensitive tape. The first puzzle from Hitchin was a small jigsaw of a Mother Goose pantomime figure and was dated 1806. The other two were maps - one of Asia (1840) and one of England and Wales (1870).

Conservation Ethics

Jigsaws are primarily ephemeral objects and this affected their conservation requirements. Social history collections are reflections of people and deal with everyday things. Since the importance of objects as sources of information cannot be overestimated the treatment ethics were necessarily of minimal intervention throughout. The unity of a puzzle is found in its combination of materials and any deliberate tampering with this would spoil and negate the 'value' to researchers and collectors. Thus separation of the layers was to be avoided, in keeping with the central tenet of preserving the original nature of the jigsaws. Moisture was also to be kept to a minimum since any such treatment would have introduced the risk of severe distortion to the original, as paper and wood have different dimensional responses. The puzzles from Hitchin would eventually form part of a 'living historical centre of education' where objects could be readily handled, and to accommodate this requirement, facsimile copies of the puzzles were produced using computer digital imaging technology. This further enabled preservation and minimal treatment to be the primary goals of treatment.

Conservation Treatment

Figure 2. Copy of the original scanned image of an 1806 jigsaw puzzle of Mother Goose before digital manipulation (click image for larger version)

All jigsaws are made to be used and surface soiling and embedded dirt was to be expected. The paper layers of the puzzles were dry mechanically cleaned. Loose dirt was brushed away and the wooden boxes were cleaned using cotton wool swabs, distilled water and Synperonic N, a non-ionic detergent. Swabbing was also used to remove grime from the varnished paper layers on the box lids. The varnish on the lids was discoloured and damaged but despite the craquelure it was decided to retain the original finish. The underlying paper layer was however protected with localised applications of gelatine in the necessary areas.

Previous repairs were removed where these were damaging to the object. The pressure sensitive tape on one of the puzzles was mechanically removed. After tape removal and the fixing of some small fugitive ink inscriptions the key pictures were washed. They were then repaired and lined using Kozu Shi Japanese paper and L4 lens tissue with wheat starch paste.

It is very common for jigsaws to have numerous losses of both entire pieces and of the interlocking tabs. The replacement of these missing areas was necessary to give the objects mechanical stability and also aesthetic coherence. The repairs were made using jelutong - dyera costulata - a wood from Southeast Asia and archivally approved western papers individually chosen for each puzzle. The wood repairs, shaped using a powered fret-saw (Vibrosaw 2000), were adhered using rabbit skin glue. A mixture of wheat and potato starch paste was used to adhere the paper layer; this was to reduce the moisture content and improve the bonding abilities. The repairs were toned using watercolours. One of the puzzle boxes had been damaged by woodworm and was structurally very weak. These losses were infilled using a mixture of rabbit skin glue and lycopodium (spores from the club foot moss of the genus lycopodium clavatum), which was then toned to match the surrounding wood. The project also considered the interaction of paper and wood, structural distortion of the puzzles and designed storage and housing solutions.

Making the facsimiles

Figure 3. Copy of the scanned image of the jigsaw after digital manipulation, enhancement and image completion (click image for larger version)

The making of copies has a tradition almost as old as art itself and the role of the facsimile puzzles was central to this project. The jigsaws were scanned into a computer and the resultant digital images were manipulated using an image processing programme, Adobe Photoshop, in effect producing 'on-screen restoration' (Figures 2 and 3). The final images were printed onto archival quality paper and used in the construction and cutting of duplicate puzzles. The use of the facsimiles demonstrates the huge potential of the application of computer technology to conservation and the wider museum field, and was accompanied by a simple computer game based on the jigsaws' images.

Conclusion

The project was beneficial in extending the working life of the puzzles through structural and aesthetic improvements, increased stability and a potentially greater educational profile. Many objects are of composite materials and increasingly collections include multimedia works of art, and the conservation treatments proposed could be of wider application on objects for which separation is not an option.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Camberwell College of Arts, Fiona Doddswell, curator of the Jill Grey Collection, the staff of the National Museum of Childhood, Bethnal Green, and the Paper and Book Conservation Sections.

July 1997 Issue 24

- Editorial

- Managing to be 'Tackless'

- The Initial Conservation of an Archive of Rolled Architectural Drawings

- The Hand of God

- The Conservation of Nineteenth Century Dissected Puzzles

- Conservation and Mounting of Leaves from the Akbarnama

- The Coronation of the Virgin - a Technical Study

- Painting in Japan

- Printer Friendly Version