Conservation Journal

July 1997 Issue 24

The Initial Conservation of an Archive of Rolled Architectural Drawings

This article outlines a six month project dealing with badly damaged archive material. It describes the size, condition and treatment of the archive and addresses some of the problems associated with salvage projects.

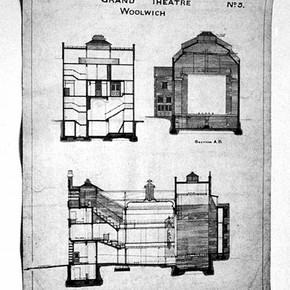

The archive represents almost all the remaining drawings produced by the firm of Frank Matcham (1854 -1920) 1 , the most prolific theatre architect of his generation (Figure 1). Although many of his theatres have been demolished, those still standing include the London Coliseum, Buxton Opera House, the Grand Theatre, Douglas and Harrogate New Kursaal. Within the archive are examples of all the major types of drawing and printing used by architects at this time, illustrating every stage of work.

Provenance, size and condition

The archive was moved from the firm's offices some 40 years ago to a barn. About three years ago when the barn was cleared out, the archive was recognised as being of significance. The Theatre Museum subsequently acquired the archive of 139 rolls amounting to between 9,000 and 10,000 drawings.

84 of the rolls had mould damage, mainly confined to one end (Figure 2). The extent of this mould damage is linked to the degradation of the material. There was heavy surface dirt and the roll ends were crumpled and torn; however smaller drawings within were found to be very well preserved.

The project aimed to make the archive accessible for accessioning and cataloguing. This involved the compilation of a condition survey and initial catalogue, remedial conservation treatments and the upgrading of storage.

Documentation

Prior to the contract a preliminary catalogue and condition survey were carried out by Pauline Webber and Phillipa Hunt from Paper Conservation. During the early stages of the contract two separate documentation systems were developed: a card file system and a survey form. The card file system enabled an overall view of the progress of the project. Basic information on each roll was recorded, including location, treatment and drawings of significant interest.

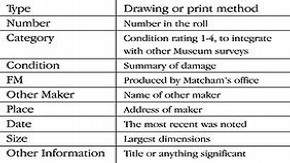

It was necessary to have a record of each drawing's location within its roll. Each drawing has an individual entry and took about three minutes to document. The survey addressed general questions about the archive and provided more specific information about particular damage to material types (Table 1). The treatment for each item was documented using another single line tick-box form.

Treatment

The rolls with mould damage were isolated and treatment began on the remaining 55 rolls. It was decided early on to flatten as many drawings as possible. This would reduce the risk of further damage during cataloguing and enable a longer term storage system to be devised. Damage to the rolls without mould was physical rather than chemical and they could be opened without humidification. Drawings were only brushed or surface cleaned if there was a lot of dust present. The amount of moisture introduced before pressing varied considerably, dictated by the substrate rather than the media. Only one ink was found to be fugitive. Some points of interest are outlined below.

-

Linen lined drawings on Whatman® paper responded best if sprayed on the verso only. This allowed the linen and adhesive longer to absorb moisture than the paper and created a more even 'relaxation'.

-

Different types of tracing paper responded differently to moisture, some papers became pliant, while others cockled badly. Therefore, some sheets were treated locally with water and then eased flat, others only required pressing for a long period, while some responded well to humidification in an ultrasonic humidity chamber.

-

Oil impregnated papers of different types were noted. Creased and folded areas were particularly brittle but a line of water, brushed along the inside of the fold, rehydrated the area and could then be eased flat. Whole sheets were placed on blotting paper and sprayed lightly with water. Polythene was smoothed onto the drawing and a weight applied. The impermeable layer above the object allowed the blotting paper to draw the moisture through the substrate.

-

Opaque linens reacted to moisture in a similar manner to cotton rag paper.

-

The image on tracing linens appears on the matt side. Water was applied locally in creased and folded areas as spraying resulted in cockling and irretrievable loss of gloss.

-

Blueprints and dyelines are both created using a sensitized photographic coating 2 and responded similarly. Moisture was applied to the verso allowing it to penetrate and humidify the paper before the photographic coating.

After completing the first section of the archive, I began to remove mould spores from the 89 rolls, in a fume cabinet. It was interesting to note which materials had been attacked by the mould; in some cases the paper had been all but destroyed while its linen lining was unaffected.

Storage

A simple, relatively inexpensive flat storage system has been devised. Up to 12 drawings will be placed in polyester film 'L-velopes' (welded along an adjacent short and long edge) and divided every third drawing with a sheet of neutral pH paper (due to the pH sensitivity of the photographic prints). Outsize drawings are to be stored rolled following T.K. McClintock's system of rolled polyester sleeves 3. Suitable shelving has been located and the whole bay will become a container; the shelves will be enclosed by attaching and folding down Tyvek®. In July 1996 the system was approved but implementation required funding.

Brief discussion

Before undertaking to collect and conserve large, badly damaged archives, certain considerations need to be taken into account. These include the condition and number of objects, the space and time available, what treatment level is expected/required and the documentation of material prior to accessioning.

The restraints of space and time should not be underestimated. Enough space is needed for rolls to be opened and worked on without restriction: a dedicated workspace should be available. To maximise efficiency, the time allocated for conservation work should be divided so that streamlined systems can be established.

In addition to assessing the physical condition of the archive for conservation purposes and identifying the material for the cataloguer, a record of specific drawing order may have significance, and as such, should form part of the documentation.

Assessment

Adaptations to treatment were necessary for processing large numbers of drawings. Time spent at the beginning, determining the rapid and effective introduction of moisture, reduced the actual working time. Time and material costs were saved by not interleaving during treatment. Finally, humidification and flattening of objects facilitated surface cleaning and did not reduce the effectiveness of the procedure.

It was possible to document and flatten all of the 55 rolls without mould damage. These rolls, amounting to 4,000 drawings, are now flat stored (Figure 3). In addition approximately 40 were repaired and linen tape was removed from a further 50. The mould was dusted from 37 of the remaining rolls, 16 of which were then humidified and pressed.

Documentation enabled a catalogue to be compiled that would draw attention to points of particular interest. Most of the ground work has been completed and preliminary cataloguing was carried out.

A dramatic improvement has been made to the state of the archive, not only physically but also in the increased accessibility to historical information.

Conclusion and closing remarks

Frank Matcham was and is an architect of national importance and until this archive came to light little was known of his working method. It had been thought that Matcham gave overall directions but had no detailed concern with his buildings; this archive presents very strong evidence to the contrary.

The archive shows the variety and diversity of architectural drawings. They are important for a number of reasons, not least because they come from and trace the development of Matcham's office. They also show the development of architectural drawings, their uses and the development of twentieth century building practices.

The project enabled a sustained period of work to be carried out and did more than fulfill the initial aim. Some drawings have already been made available to architects working on renovation or restoration projects, specifically the London Palladium. It is possible, with the right space, facilities, aims and single-minded approach, to collect and treat this type of salvage material and to make significant improvements to its condition.

References

1. Walker, B., ed., Frank Matcham - Theatre Architect, Blackstaff Press, 1980.

July 1997 Issue 24

- Editorial

- Managing to be 'Tackless'

- The Initial Conservation of an Archive of Rolled Architectural Drawings

- The Hand of God

- The Conservation of Nineteenth Century Dissected Puzzles

- Conservation and Mounting of Leaves from the Akbarnama

- The Coronation of the Virgin - a Technical Study

- Painting in Japan

- Printer Friendly Version