Conservation Journal

April 1998 Issue 27

Miniature Paintings, Paper, Paintings, Parrots, Elephants and Monkeys - A Study Trip to India

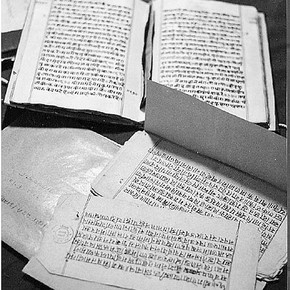

Figure 1. Manuscripts in Jodhpur Library. Phogoraphy by Anna Hillcoat-Imanishi (click image for larger version)

As soon as I started my course at the V&A people started talking about sending me to India - surely, I thought, they can't want to get rid of me this quickly, but... I was suddenly on my way in October 1997, with the aid of a generous travel grant awarded by the Nehru Trust, and further financial help from the RCA. My mission was five-fold: to find the collections of Indian miniature paintings; to find conservation studios; to find and meet practising miniature painters and historians who would enlighten me; to learn about India and, finally, to write about it all. Delhi, Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Udaipur, Jaipur, Agra, Gwalior and Delhi were to be the eight stations of my journey.

In Delhi I was received by Manjit Debasis and his family, who very kindly allowed me to stay in their home. This gave me a unique insight into the everyday life of a Delhi family. I also acquired an in-depth understanding of some of the problems of government-funded conservation and museums, as Manjit is a paintings conservator who spent time in the V&A as an intern a few years back.

I visited the National Craft Museum, whose director, Jotindra Jain, although very busy, spent a lot of time with me explaining the philosophy behind his collection. The objects are all displayed in a very contextual way, the floors covered with rush matting and the natural clay walls covered with traditional wall paintings. The entire museum building is an example of Indian craftsmanship, as well as the objects it displays. Although the museum is fairly small it has a conservation studio employing three conservators. Storage is very accessible and highly visible with objects shelved in glass cases, as the store is also the study collection.

In the National Museum of Art I was not quite so lucky. The curator I had contacted, and whom I wished to take me around the collection, reserve and stores, had forwarded my letter on to a conservator, who happened to be on holiday. When I returned at a later date, the curator was not available.

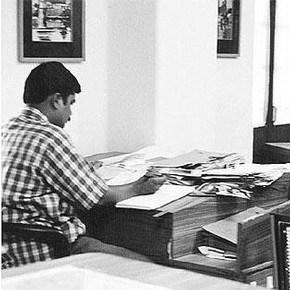

At my next stop, in Jodhpur, I was taken care of by the charming Dr Naval Krishna of the Jodhpur Palace Museum. After a guided tour of the fort, where the museum is located, I visited the newly established conservation studio led by Alok Kumar. He had trained under Agrawal in the Indian Conservation Centre at Lucknow, specialising in mural paintings. Two other conservators were working under him, and with the support of the Indian Conservation Institute, a good studio has been installed at the fort. Here, the conservators work on the vast and varied collections of the Maharajas of Jodhpur, ranging from elephant howdahs and weapons to tantric meditation drawings and ancient manuscripts. The conservators are doing an amazing job considering the difficulties encountered when trying to obtain materials and funds to carry out projects.

Figure 2. Alok Kumar and colleague in the conservation studio of the Mchangarh Trust. Photography by Anna Hillcoat-Imanishi (click image for larger version)

I was also shown the textile stores, the weapons collection and the library. Here books, manuscripts and loose papers are kept wrapped in the traditional way, where each pack of pages belonging together is placed in an envelope, and stacks of about 50 envelopes are kept between slightly larger wooden boards and then tied up. This bundle is then wrapped with red cloth and again secured with ribbon. The contents of this the bundle is are written on a piece of paper which is attached to the bundle. The important pieces are kept in lockable metal fireproof cabinets. In this way the library houses about 5000 manuscripts, together with 7000 account books of the palace, which are kept slightly more loosely on wooden shelves behind polythene sheets.

In Jodhpur I also had the opportunity to observe the Dussera festival and to ride on the back of the scooter carrying the ceremonial sword of the assistant museum director.

Jaisalmer had no direct museological connection, but here I learned how miniatures are traditionally kept on display in private houses. In one of the havelis (houses with a courtyard dating back to the 16th century), miniatures were let into the plaster of the wall and covered with a pane of glass with an ornamental plaster frame.

In Udaipur I had no letter of introduction and could therefore not see behind the scenes of the City Palace Museum, which I deeply regretted. I visited the Government Museum which has a good collection of miniatures, housed in cases alongside spiders and chipmunks. There was a catalogue at the reception, but I was told by the warding staff that it was absolutely not available to me. This was frustrating as Dr Sharma from the Mewar Research Institute had assured me that the catalogue contained valuable information.

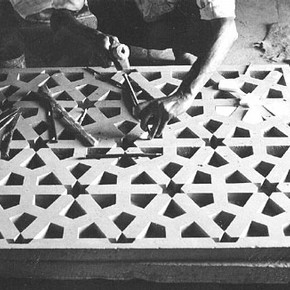

Figure 3. Stonemason making a sandstone filigree screen with white marble infills in Agra. Photography by Anna Hillcoat-Imanishi (click image for larger version)

In Jaipur I met with Dr Das for an art historical exchange over tea and rose biscuits. Mr Sahai from the Palace Museum showed me the store and told me about some conservation problems he had (example: paper cuts made from gold leaf stuck between glass panes, which would crumble into dust when touched, but which have to be removed from their casing because they have slipped). I also met with Dr Hot Chand of the Government Museum. He and I had interesting discussions over the necessity of some treatments currently standard in Indian paper conservation such as washing, deacidification and bleaching of paintings, as well as ethics in general.

I also met with Bannu Ved Pal Sharma, a traditional miniature painter who also works as a restorer. He was able to give me a lot of practical information on painting, materials and restoration. It was fascinating to hear him explain his painting techniques and to see his burnishers and brushes.

Finally, I visited the Kumarappa National Handmade Paper Institute in Sanganer. Here, research is under way into finding paper-making materials that are easily obtainable and cheap for village paper production. Mr Singh of the Institute showed me a traditional paper-maker's house, where Mohammed Kagzi and his family make paper by hand from recycled old rag paper and jute fibres. He uses the traditional flexible mold, squatting before his vat. His wife brushes the damp sheets onto the house wall to dry, and they are burnished by hand over a curved slab of wood with a little linseed oil.

In between visiting museums, I managed to see some of India's better known sights: amazing giant Jain statues in a cliff face at Gwalior; at Agra, breathtaking Mughal monuments and, of course, the Taj Mahal..

All in all I learnt a lot on this study trip, not only about conservation, but also about museum politics, amazing craftsmanship, endurance, Mughal history and the beauty of India. And I didn't get ill once.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my thanks: to everyone who helped me during my trip; to the Nehru Trust and to the RCA for providing funding; and also to Dr Deborah Swallow for planning my itinerary.

April 1998 Issue 27

- Editorial - British Galleries

- The New British Galleries at the V&A

- 'Natural Born Quillers' - Conservation of Paper Quills on the Sarah Siddons Plaque Frames

- A New Book Mount

- Photography in a New Light

- The Conservation and Mounting of a Jinbaori

- Textile Symposium 97 - Fabric of an Exhibition: An Interdisciplinary Approach

- Miniature Paintings, Paper, Paintings, Parrots, Elephants and Monkeys - A Study Trip to India

- Printer Friendly Version