Conservation Journal

October 1998 Issue 29

50 Years of Following In Grinling Gibbons' Tool Cuts

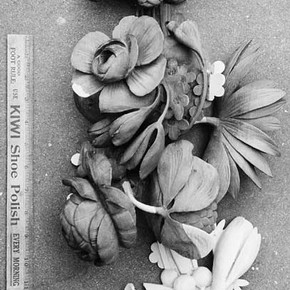

Figure 1. Repairs to Grinling Gibbons carving from the Quire (limewood). Photograph by Hannah Hartwell (click image for larger version)

In 1951 the word 'restoration' was a word I always associated with fund raising, whilst 'conservation' was never used at work. We were simply 'repairing' the damage caused by the bombs during the war. The word repair at that time covered a wide spectrum, from collecting and reassembling small fragments of carving from the rubble, to carving what someone thought might have been there before. I can never remember a carver 'researching' what could have been there.

Those were the 'good old days' with many beautiful Wren churches to rebuild and decorate with their Grinling Gibbons style of carving. The long tradition of each firm having its own interpretation of an architectural style meant that journeyman craftsmen would have to change their style to suit. Good examples of this in St Paul's Cathedral are the twentieth century woodcarvings by J. Walker in the St Michael & St George Chapel, the Rattee and Kett work in the American Chapel and the E. J. Bradford's limewood carvings on the Pulpit, all done within a forty year period.

In 1972 I joined the carving team at St Paul's under Ken Gardner who had trained me at Bradford's, so it was therefore natural for us to continue in the same style. Outside on the South Portico, compare the four new 'incense potts' carved by us with the originals carved by Caius Cibber in a style almost indistinguishable from Gibbons, two of which are displayed in the crypt. Their silhouette may be similar, but their delicacy and finesse are lost. This freedom for interpretation is certainly not acceptable these days, and while I have illustrated this with examples from St Paul's, there are certainly other examples.

In the early eighties I took control of the carving department and with the Surveyor to the Fabric agreed to make changes. At this time, whilst working on Wren's Great Model, I became involved with the Conservation Department at the Museum of London, a totally new experience for me and probably the biggest single change in my working life. From now on, all decisions would have to be questioned, and no longer could it be said, 'that's how we've always done it'.

Recently there has been a restoration to the Grinling Gibbons carvings in the Quire at St Paul's, where a major change in philosophy has taken place. I knew that when the carvings were returned from safe keeping during the war, they had been refixed in a hurry and were in a sorry state as a result. Most of the carvings had been fixed with too many iron nails (up to five in one flower), most of which have rusted and expanded, splitting the wood. The old animal glue was drying out and the joints were opening up. The oak carvings had been treated with generous amounts of linseed oil and turps to five them a shine, which is unacceptable now.

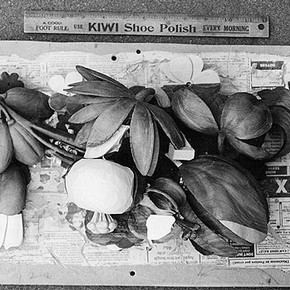

Now, after the carvings are taken down, they are dusted before being lightly washed. As many nails as possible are removed without damaging the wood, and they are then repaired using new limewood fixed with PVA adhesive. New pieces are only added when evidence is available from old photographs, where there is an identical pair or a repeated pattern. They are then refixed in the Quire with a minimum number of brass screws, which we try to keep to a system, by fixing all the swags with the same number of screws in the same place according to size and design. A lot of damage has been caused in the past by taking down and refixing the carvings without any regard to previous fixings or future removal. This is, after all, the fourth time they have been fixed in the Quire, and, no doubt they will come down again, but at least we have eliminated this major cause of damage.

Figure 2. Repairs to Grinling Gibbons carving from the Quire in progress (limewood). Photograph by Hannah Hartwell (click image for larger version)

The carvings are no longer fixed in a random way, but according to a grand plan which I believe is suggested by the design. For example, swags of oak leaves alternate with swags of acanthus leaves, and swags of flowers which have an identical pair now sit opposite each other across the aisle. Many pieces are right- or left- handed and once you know this, it is very annoying to see two right handed pieces together. It is also amazing how many have been fixed either upside down or totally in the wrong place. We may not get it right every time, but at least we are aware now.

The Quire was photographed before we started making these alterations and we now have a conservator on the staff who is recording everything, so I feel comfortable with rearranging the carvings. Working as a team, we spend time debating where a piece should fit, and how to deal with a particular problem, and still we make changes when new evidence is found. This is one big advantage of having a permanent team.

There has always been discussion as to how Wren intended the woodwork to be finished and I have heard talk of ox blood being used to stain the wood. However the facts as I see them are:

1. The original surplus oak carvings which have been left untouched in the store since the 1861 alteration are not as dark in colour as the carvings in the Quire.

2. Where oak mouldings are out of easy reach they are lighter than the ones that are easy to stain.

3. When applied limewood carvings are removed they leave a lighter shadow.

These observations give rise to the question, is this due to natural ageing or deliberate staining. The current policy is to colour the new carved pieces, which will be undertaken later as a single project rather than individual pieces, to obtain a uniform colour across the Quire.

While working at St Paul's it is important to remember that we are not a museum but a working Cathedral, which happens to have some of the world's finest seventeenth century carvings. After they have been cleaned, repaired and refixed they will get dusty and may be accidentally damaged, because they are part of the fabric, not objects in glass cases.

Over the last fifty years attitudes have changed enormously to restoration, and no doubt will continue to do so. Although I miss the opportunity to carve new work, the more I work on the Grinling Gibbons carvings, the more new discoveries I make about them, and the more stunning I find them.

October 1998 Issue 29

- Editorial - Communication

- The Cosimo Panel

- 50 Years of Following In Grinling Gibbons' Tool Cuts

- Cracking Crizzling - Eight Years of Collaborative Research

- The Power of the Poster and Paper Conservation

- The RCA/V&A Conservation Course Study Trip

- Science Surgery

- Editorial Board & Disclaimer

- Printer Friendly Version