Conservation Journal

Spring 2000 Issue 34

'My Picture Is A Sum Of Destructions', Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

'I can hardly understand the importance given

to the word

research in connection with modern painting.

In my opinion to search means nothing in painting.

To find is the thing.

Nobody is interested in following a man who, with his eyes fixed on the ground, spends his life looking for the pocketbook that fortune should put in his path. The one who finds something no matter what it might be even if his intention were not to search for it, at least arouses our curiosity, if not our admiration.'Statement by Pablo Picasso, 19231

Figure 1. Nude Woman with Necklace, 1968, drying oil and oil/alkyd on canvas, 1135mm x 1617mm. Tate Gallery, London (cat no. T03670) being examined with a stereo microscope © Succession Picasso/DACS 1999. Photograph by Fotini Koussiaki (click image for larger version)

A project to study the influence that synthetic painting materials had on the technique of Pablo Picasso is underway at the Tate Gallery. This is the subject of my MPhil research. My research strategy is to subject fourteen Picasso paintings from the Tate's Collection to a strict programme of examination and detailed analysis (Figure 1). In addition, a number of paintings from other museums and private collections are to be sampled.

As early as 1912, Picasso used materials that were commonly used for other well-defined purposes besides fine art practice, such as household or architectural use and even industrial coatings, which he used along with artists' paints. During his cubist period he solved his problem of achieving bright colour by introducing Ripolin (shiny house paint) instead of artist's oil paint. In talking about the Ripolin paints, he named them, 'le santé des couleurs, (that is why) they are the basis of good health for paints'2 .

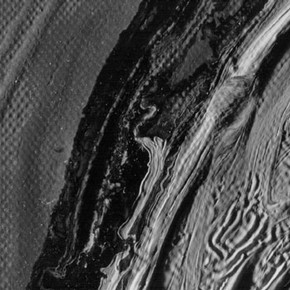

Figure 2. Detail of wrinkling colours in Nude Woman with Necklace, Tate Gallery London. © Succession Picasso/DACS 1999. Photograph by Fotini Koussiaki (click image for larger version)

During the 1940s, Picasso's photographer and friend Brassaï, gathered a rich source of information from his notes of visits to Picasso. This is how he described Picasso's order for colours:

'Then the man in the blue suit reaches into his pocket and takes out a large sheet of paper, which he carefully unfolds and hands to me. It is covered with Picasso's handwriting-less spasmodic, more studied than usual. At first sight, it resembles a poem. Twenty or so verses are assembled in a column, surrounded by broad white margins. Each verse is prolonged with a dash, occasionally a very long one. But it is not a poem: it is Picasso's most recent order for colours:

White, permanent------------------------

Figure 3. Seated Woman in a Chemise by Picasso, 1923, oil on canvas, 922mm x 730mm. Tate Gallery London (cat no. N04719) © Succession Picasso/DACS 1999. Photograph by Fotini Koussiaki (click image for larger version)

argent --------------------------

Blue, cerulean---------------------------

cobalt-------------------------

Prussian----------------------

Yellow, cadmium lemon (clear)------------

strontium----------------

Lake, madder ---------------------------

blue and brown-----------

blue violet-----------------

Black, ivory--------------------------------

Ochre, yellow and red--------------------

Ultramarine, clear and deep--------------

Umber, natural and burnt------------------

Red, Persian-----------------------------

Green, cadmium, clear and deep------------

Sienna, natural and burnt-------------------

Green, emerald-------------------

Japan, clear and deep----------------

Veronese---------------------------

Violet, cobalt, clear and deep-----------------It made one think of Rimbaud's "Les Voyelles". For once, all the anonymous heroes of Picasso palette trooped forth from the shadows, with Permanent White at their head. Each had distinguished himself in some great battle - the blue period, the rose period, cubism, "Guernica"… Each could say: "I too, I was there…" And Picasso, reviewing his old comrades-in-arms, gives to each of them a sweep of his pen, a long dash that seems a fraternal salute: "Welcome Persian red! Welcome emerald green! Cerulean blue, ivory black, cobalt violet, clear and deep, welcome! Welcome!"'

Brassaï's notes, Thursday, November 18, 19433

Figure 4. Seated Woman in a Chemise in raking light © Succession Picasso/DACS 1999. Photograph by Marcella Leith (click image for larger version)

Binding media in Picasso's paintings are characterised by pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (PyGCMS) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The problem in identifying early 20th Century housepaints lies in distinguishing them from oil paint, as both were based on linseed oil. Later alkyds also derived from oil and, moreover, sometimes they were mixed with oil on the artist's palette before the application to the canvas4 (see Francesca Cappitelli's article in this issue of the V&A Conservation Journal).

Besides the identification of the components of a great number of samples, the information that I find most helpful comes from their origin. Picasso was a master of painting techniques; if he was using traditional materials but found an area that required a paint of extra brilliance, he would simply add medium or change the type of paint that he was using (Figure 2). Sometimes he would simply squeeze from the tube the first colour he found on his table. Consequently, the analysis of the media in several colours from the same painting, shows that several types of colour were used in each.

Figure 5. X-radiograph mosaic of Seated Woman in a Chemise, showing an earlier version of the painting, incorporated into the hands and figure of the final painting. © Succession Picasso/DACS 1999. X-radiography by Mark Heathcote (click image for larger version)

The comparative study of photographs taken of each work, within the visible, infra-red (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) section of the spectrum as well as the X-ray, properly confirm Picasso's comment:

'The old days' pictures went forward toward completion by stages. Every day brought something new. A picture used to be a sum of additions. In my case a picture is a sum of destructions. I do a picture - then I destroy it. In the end, though, nothing is lost: the red I took away from one place turns up somewhere else.'

Statement by Pablo Picasso, 19355

What began as a preliminary investigation of materials and techniques led to a thorough appreciation of Picasso's technical skill.

Picasso had no desire to hide the process of painting6. In most cases he left visual clues on the surface of the final painting. Often the alterations that were made in a painting could be first detected by using simple visual methods like raking and transmitted light or by a more detailed observation using a simple microscope. The result of an alteration on the painting may be observed as a certain crackle pattern, a different colour showing through a crack or an unusual anomaly on the surface.

To confirm observations that are the result of his active brushwork, infrared light and X-rays are used to penetrate the visible image. Comparison of the x-radiograph mosaics and the infrared photographs with the visible image of the paintings often surprises by revealing not only paint changes but also a hidden image (Figures 3-5).

Are we entitled to uncover an image that the artist reworked for some reason? Knowledge of an earlier painting or a previous version, enables researchers to follow in their imagination the steps that the artist took in realising his inspiration. Picasso expressed his thought about this, giving us the green light!

'It would be very interesting to preserve photographically, not the stages, but the metamorphoses of a picture. Possibly one might then discover the path followed by the brain in materialising a dream.'

Statement by Pablo Picasso, 19357

Acknowledgements

With thanks to all in the Science Section and the Painting Conservation Studio at the Tate Gallery. In particular I would like to thank Tom Learner for his invaluable advice, Marcella Leith for the photography and Mark Heathcote for the x-radiography. Also thanks to Greek State Scholarships Foundation who provides the funding for the present research work.

References

1. Statement made in Spanish to Marius de Zayas. Published in 'The Arts', New York, May, 1923 under the title Picasso Speaks. Reprinted in: Barr H.A., Jr, Picasso, Fifty Years of his Art, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946, p.270.

2. Richardson J., 'A Life of Picasso, Volume II: 1907-1917', London, Jonathan Cape, 1996, p225.

3. Brassaï G. H., Conversations avec Picasso, Paris, 1964; translated by Francis Price as Picasso and Company, Garden City, N.Y., 1966, p.87, p.88.

4. Learner, T.J.S., The Analysis of Synthetic Resins Found in Twentieth Century Paint Media, in Resins Ancient and Modern, eds. M.M. Wright and J.H. Townsend, SSCR, 1995, pp.76-84.

5. Statement to Christian Zervos at Boisgeloup. Published in 'Cahiers d'Art', 1935, volume 10, number 10, p.173-8, under the title Conversation avec Picasso. Reprinted in: Barr H.A., Jr, Picasso, Fifty Years of his Art, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946, p.272.

6. Hoenigswald, A., Works in Progress: Pablo Picasso's Hidden Images. In

McCully, M. Picasso, The Early Years 1892-1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Yale University Press,1997, pp. 299-309.

7. Barr H.A., Jr, 1946 op cit

Spring 2000 Issue 34

- Editorial - A New Look For The Conservation Journal

- Contemporary V&A

- Twenty First Century Conservation

- Science Surgery: The Contemporary Challenge

- Masters Not Slaves - New Technology In The Service Of Conservation

- Difficulties In The Scientific Study of Synthetic Materials In Paints

- SIGGRAPH 99, Or Why A Conservator Should Attend A Graphics Conference

- 'My Picture Is A Sum Of Destructions', Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

- Printer Friendly Version