Conservation Journal

Summer 2000 Issue 35

Oh, The Shark Has Pretty Teeth, Dear

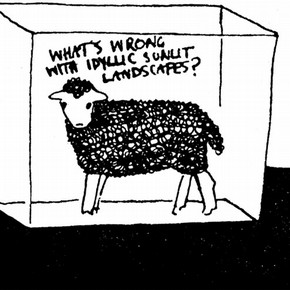

Figure 1: Min Cooper, What's Wrong with Idyllic Sunlit Landscapes? Reproduced with kind permission from Min Cooper (click image for larger version)

The past decade has witnessed substantial and well-documented developments within British art practice and art history. The Turner Prize and its attendant exhibitions at the Tate Britain, successful and highly publicised exhibits at the Saatchi and Serpentine Galleries1, and the infamous 'Sensation' shows in London (1997) and New York (1999-2000) have led to certain British artists and artworks acquiring international reputations and critical praise.

Notably, however, these artists have created their most acclaimed works to date by using ephemeral or unconventional materials such as lambs, cows, and blood, pushing their materials' boundaries in ways that, until the end of the 20th century, were alien to fine art practice. The rates and deterioration mechanisms of such materials are virtually unknown to conservators and thus provoke challenging questions within the arenas of conservation, curating, collecting, and artistic practice.

One artist whose work prompts analysis of the ramifications of employing unusual materials is Damien Hirst. Hirst's work arguably epitomises the vicissitudes of contemporary artistic media, famously transmuting the tradition of landscape painting into sinister gallery installations (Figure 1). His most notorious sculpture, 'The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living', features a 14-foot tiger shark suspended within a glass tank filled with a 5% formaldehyde solution. Viewed from the front, the shark confronts the viewer with his teeth bared, seemingly poised for attack.

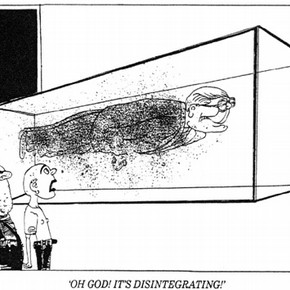

'A shark is frightening, bigger than you are', Hirst declared 2, and it is indeed these notions of power and danger that critics originally ascribed to the sculpture and often cited as one of its most important elements. Yet Hirst's shark has deteriorated noticeably since its creation in 1991. By 1997, when it secured the first gallery of the Royal Academy's 'Sensation' exhibition, even casual observation revealed it to be straining its seams. I have yet to determine when this decomposition began, but Michael Heath's cartoon of a disintegrating John Major suspended in a Hirst-like tank (Figure 2) suggests that news of the shark's decay entered the public arena as early as 1992, only a year after the work's completion. In any event, it didn't take long for media comments about the shark's dilapidation to circulate.

David Lee reported, 'No sooner had the papers tired of [the shark] than further reports of it leaking and rotting…were drip-fed like plasma to news desks'.3 Norman Miller described it as 'going soft' and noted that the formaldehyde formula Hirst employed was 'not quite cutting the mustard. Unless a new formulation is found soon, the shark will droop'. 4 And Kitty Hauser, in a caustic critique of 'Sensation' , advised New Left Review readers to 'look closely through the formaldehyde at Damien Hirst's shark…It is more than a little moth-eaten; the surface of its skin has been patched and retouched'.5

Figure 2. Michael Heath, Oh God!, Its Disintergrating!, The Independent, 24th November 1992. Reproduced with kind permission from The Independent (click image for larger version)

I would argue that this decay potentially undermines the vital concepts of power and menace that the sculpture originally inspired. Its perceived softness blunts its power; its moth-eaten skin negates its element of danger. As Waldemar Januszczak lamented in 1997, 'A sadder, smaller, less aggressive beast stares slowly at you from inside its mysterious glass coffin'.6

Stripped of its threat by deterioration, the shark no longer conveys Hirst's idea of menace contained. Nor does it realise his stated intention of making the shark look life-like in order to represent 'the obsession with trying to make the dead live or the living live forever' (Morgan, p. 24). Crucially, then, by weakening the sculpture's ability to embody its core concepts, the decay damages that which has rendered it one of the most important artworks of the past ten years.

Amazingly, 'The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living' achieved cultural prominence almost immediately, a breathtaking achievement for a work by a relatively unknown artist. It was displayed at the Saatchi Gallery in 1992 for only a few months before disappearing from public view until 1997's 'Sensation' exhibition. Yet a wide range of critics and art historians attest to its primacy within contemporary British art history. Januszczak, for example, has commented that the work 'has been photographed so often, commented upon so frequently, that its place in the art history books is already guaranteed. Even those that have never seen it will probably have heard of it' (Januszczak, p. 4). Richard Cork described the sculpture as 'one of the defining works of the decade'7 and Gordon Burn related that,

'Photographers were constantly despatched to Boundary Road in North London and their pictures reproduced with the kind of frequency which invested the shark with considerable power as an image and deepened its mystery: silent, immobile, latently lethal, suspended for eternity in its secure vitrine, it became a kind of logo of the times; a blank and yet peculiarly charged emblem'.8

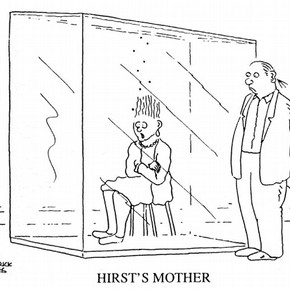

Figure 3. Meyrick Jones, Hirst's Mother. Private Eye, 17 June 1994. Reproduced with kind permission from Private Eye Magazine (click image for larger version)

Public fascination with the sculpture inspired myriad parodies, further emphasising its cultural eminence. Meyrick Jones' cartoon of 'Hirst's Mother' (Figure 3) especially reinforces the art historical significance of both artist and artwork by invoking the canonical stature of James McNeill Whistler and his most famous painting, 'Arrangement in Grey and Black' ('Whistler's Mother'). Jones's allusion to Whistler seemingly accords Hirst and 'The Physical Impossibility of Death'… the lofty cultural position enjoyed by Whistler and his painting, implying that the contemporary artist's work succeeds in the tradition of the earlier artist.

The challenge that the sculpture's deterioration presents to conservators is therefore considerable. Not only must they face restoring to the work its ability to incarnate the concepts Hirst has endeavoured to convey, but they must also negotiate the thornier issue of the work's decay in relation to its iconic status.

Another conservation dilemma the sculpture generates involves its owner, Charles Saatchi, and the extent to which we expect him to assume liability for preserving the work. In fact, the shark's deterioration highlights the implications for the private collector of retaining responsibility for conserving impermanent works of art in general, and those currently deemed to be of national cultural value in particular. Whilst the confines of this article prevent me from fully exploring this issue here, it is important to note that whether Saatchi ultimately repairs, replaces, or relinquishes the work, embedded within all of these options are a complex array of ethical consequences. However, having commissioned Hirst's sculpture in 1991 and supported its exhibition internationally ever since, we may presume that Saatchi sustains both a personal and a communal interest in preserving its integrity.

For Hirst, part of the work's integrity lies in its use of a 5% formaldehyde solution, a formula that may have hastened 'The Physical Impossibility of Death'…'s dilapidation. Conservation scientists have queried the wisdom of employing a weak formaldehyde solution to preserve an entire shark, especially long-term. Yet a stronger solution would render the liquid cloudy, obscuring the shark, and might prove equally incapable of prolonged preservation. Hirst himself seems unconcerned. Speaking to Stuart Morgan, he revealed:

'I did an interview about conservation and they told me formaldehyde is not a perfect form of preservation…what are you going to do about it? I said I'm not going to do anything, that's the piece. They actually thought I was using formaldehyde to preserve an artwork for posterity, when in reality I use it to communicate an idea' (Morgan, p. 61).

Additionally, he has claimed that the shark is incidental to the work, the formaldehyde crucial. 'The huge volume of liquid is enough. You don't really need the shark at all' he wrote in his book 'I Want to Spend the Rest of My Life Everywhere, with Everyone, One to One, Always, Forever, Now' (p.282). But in 1995, Hirst rejected a stronger (25-30%) formaldehyde solution for another formaldehyde-based work, 'Mother and Child, Divided ', as unsuitable for his purposes, presumably due to its murkiness.9

Hence, Hirst poses a dilemma for conservators contemplating his work. Whereas the sheer volume and opaline appearance of the liquid might be achieved through other stable, shark-friendly means which retain the actual effect of the work, he could credibly maintain that eliminating or adjusting the formaldehyde solution would alter the meaning of his work, and thus its integrity. As the shark continues to decay, and interventive measures seem ever more unavoidable, such ethical concerns will spring to the fore.

Whilst being interviewed in his Bloomsbury office in 1998, Hirst demonstrated his love of art by referring his interviewer to eight Andy Warhol silkscreen paintings. ''That man is dead,' he said, pointing to the Warhols, 'but his work is still here'.10 Ironically, the notion of immortality Hirst delights in may elude his own practice unless we evaluate the extent to which collectors, conservators, curators, and artists understand the unusual materials he and his contemporaries utilise, the ethical and practical problems they may engender, and potential solutions to their disintegration.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Board and the Royal College of Art's Conservation Department for supporting my research into the conservation of ephemeral and unconventional materials in contemporary British art.

References

1. In particular, 'Young British Artists' and 'Young British Artists II' at the Saatchi Gallery in 1992 and 1993 respectively, 'Some Went Mad, Some Ran Away' at the Serpentine Gallery in 1994 (and then to Helsinki, Hannover, Chicago, and Copenhagen), and Cornelia Parker in collaboration with Tilda Swinton at the Serpentine in 1995.

2. Stuart Morgan, 'Life and Death,' Frieze , pilot issue, Summer 1991, p. 24.

3. David Lee, 'Damien Hirst,' Art Review, June 1995, p. 8.

4. Norman Miller, 'Open-Art Surgery,' The Independent on Sunday , 6 December 1998, Review, p. 62; 63.

5. Kitty Hauser, 'Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection,' New Left Review , no. 227, January-February 1998, p. 160.

6. Waldemar Januszczak, 'Facing the Scary Art of Our Time,' The Sunday Times , 21 September 1997, Culture, p. 4.

7. Richard Cork, 'Everyone's Story is So Different: Myth and Reality in the YBA/Saatchi Decade,' in Young British Art: The Saatchi Decade , eds. Robert Timms, Alexandra Bradley, Vicky Hayward (London: Booth-Clibborn Editions, 1999), p. 18.

8. Gordon Burn, 'Is Mr. Death In?' in I Want to Spend the Rest of My Life, Everywhere, with Everyone, One to One, Always, Forever, Now by Damien Hirst (London: Booth-Clibborn Editions, 1997), p. 298.

9. Dr Joyce H. Townsend, e-mail to the author, 11 April 2000.

10. Peter Aspden, 'A Book, to Judge by Its Cover,' Financial Times, Weekend , 5-6 September 1998, p. iv.

Summer 2000 Issue 35

- Editorial

- Oh, The Shark Has Pretty Teeth, Dear

- Wolbers' Course - A Review

- Conservation of Indian Mica Paintings

- Conservation Scientists' Group Meeting: Accelerated Light Ageing

- Conservation Treatment of a 17th Century English Panel Painting

- Review of the Conservation Staff Residential Meeting

- Improved Methods of Storage for Illuminated Manuscript Fragments on Parchment

- From Strength to Strength: Recent Successes for RCA/V&A Conservation Students

- Printer Friendly Version