Conservation Journal

Spring 2001 Issue 37

Four Terabytes and Counting

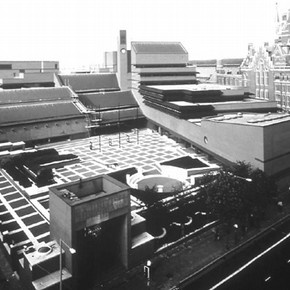

Figure 1. The British Library designed by Sir Colin St John Wilson, next to St Pancras Station, London, opened in May 1998. 'By Permission of the British Library' (click image for larger version)

I was asked to write a short piece for this issue of the V&A Journal about 'size', from the perspective of having been at the British Library for two and a half years, after 14 years in the Conservation Department of the V&A.

The British Library is big. It is the largest cultural body in the Department of Culture, Media and Sport's firmament, with current annual grant-in-aid of £83m and it generates a further £32m per year. There are 2300 staff. It is the second largest library in the world, after Library of Congress, and roughly the same as the Bibliotheque Nationale de France. The new building at St Pancras was the most expensive public building in the UK - until the Millennium Dome was completed. It has 400 kilometres of storage, housing 18 million books, 115 single items, 40 million patents etc, etc.

The collections span newspapers, periodicals, printed books, theses, 'grey literature', manuscripts, maps, patents, prints, drawings, globes, photographs, philatelic material, music, sound and video, from paper to parchment, papyrus to birchbark, wax cylinders to DVDs. The collections range from the purely informational to the artefactual. The Oriental collections include both the India Office Archives and the most exquisite oriental manuscripts and scrolls. When the British Library was formed in 1972 out of the British Museum Library, the division of the Oriental collections was, very roughly, objects with text went to the BL, objects without to the BM.

The collection is growing, largely due to legal deposit. By law, one copy of everything published in the UK must be deposited at the BL (the other five copyright libraries have the option of requesting a copy) and given that there is more material being published than at any time in the history of the world, the collections are increasing. Compounded with a growing, diversifying collection, is an increase in use (half a million reader visits per year to the reading rooms at St Pancras, consulting 3 million items) resulting in inevitable mechanical wear and tear to the collections - and so the preservation need is growing.

The Preservation Department reflects the diversity of the collection. It is one of the largest in the country, with over a hundred staff and substantial external contracts for binding, conservation and preservation microfilming. The Preservation Department encompasses conservation studios and preservation activities. Within the Conservation sections, activities range from occidental book conservation to a Kasemake machine producing phase boxes in a few minutes. Within Preservation, activities range from salvage control to collection care, from EU leather and photographic conservation projects to condition surveys, from monitoring the macroenvironment of a new building to developing anoxic microenvironments for storage. The department is on several sites, including Colindale newspaper library.

So much for tangible size. Ironically, one of the largest preservation issues is physically the smallest.

There are already about four terabytes of digital material, consisting of both 'born digital' material (i.e., it has never existed in anything but electronic form) and 'digitised' material (i.e., where a physical equivalent exists from which an electronic copy has been made). This is set to grow for a number of reasons. There is currently a voluntary code for the legal deposit of electronic material, but legislation for legal deposit is thought to be about two years' away. The explosion in electronic publishing is well rehearsed, particularly in the academic arena - for example, it has been estimated that in the next five to ten years between 65 and 95% of all scientific journals will only be produced electronically.

The BL has just started designing a 'Digital Library System' which will provide the infrastructure for the long term access to and archiving of its digital collections. All this digital material requires active intervention to ensure its survival. The Digital Library System contract was awarded to IBM and the project is working with the Royal Library in The Hague. The Digital Library Store can conceptually be seen as the electronic equivalent of the vast basement stores underneath the piazza by the Euston Road, in the new St Pancras building (fig 1). It will be able to hold large amounts of digital material but will itself be essentially a relatively small grey box with wires.

Figure 2. Sir Eduardo Paolozzi's sculpture of Sir Isaac Newton (after William Blake) in the piazza of the British Library. 'By Permission of the British Library' (click image for larger version)

There are a number of strategies being posited for preserving digital material, for example migration and emulation. However no one strategy has been tested and proven yet, so the field is wide open for imaginative and innovative solutions.

One of the most delicious ironies I have come across in this extremely fast-moving world of the digital preservation is the 'HD-Rosetta' product. This is a disc made of selenium, 50.8mm in diameter. It can hold 340,000 microimages which are inscribed onto the surface. It requires a microscope and video camera to read. Therefore, at the moment when there is no time-tested method of guaranteeing continued access to electronic information, it is commercially viable for a company to provide a tangible, physical, minutely-scaled solution. So the world comes full circle from the Rosetta Stone 2200 years ago. This product is essentially using nanotechnology, which is one of the major features of the age, in the service of the preservation of one of the biggest challenges.

Another scale-related feature of the age is globalistation and a major facet of that is the internet. One question the British Library is grappling with is - 'should a national library archive the web'? The National Libraries of Sweden, Denmark and Australia all have initiatives, for example the Royal Library of Sweden's Kulturarw_project, which robotically harvests everything with a Swedish web address every three months, or the National Library of Australia's Pandora project, which selectively downloads about 80 titles from the web.

Even looking with a narrow, national perspective, the scale of the web is not only vast, but also amorphous and diaphanous. In order to address such a potentially huge issue, selection is probably the key to making it manageable. The British Library is about to be a founding partner in a 'Digital Preservation Coalition' which will deal with some of these issues, as it is a truism in this field to look for distributed, collaborative solutions.

An interesting comparison between one topic I was dealing with at the V&A and which has to be addressed electronically at the BL, is that of collecting the design, or creative, process. The Prints, Drawings and Paintings Department of the V&A collected the creative process, for example, of a Dyson vacuum cleaner or an Alessi kettle. In the National Art Library, a major project was the conservation of Charles Dickens' manuscripts, which was in essence, conserving the literary process.

The crossings-out of manuscripts are often the most informative element for researchers, and revealing cancelled manuscripts (by photographic means rather than having to physically intervene and remove wafers) was a feature of that project. At the BL, there is a project using UV, IR, 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional digital imaging to reveal text in fire-damaged Cotton Collection manuscripts.

The issue for the British Library is that with the use of the personal computer by writers, how do you conserve the electronic equivalent of Dickens' paper manuscripts, with their cancelled text and revisions and the equivalent of Dickens' correspondence? The latter is often of most use to researchers. The electronic equivalent would be preserving e-mail correspondence, and a project is being formulated in conjunction with a literary author to see what this entails.

This might seem a small matter, but these sorts of issues are set to have an impact on all government bodies, whether a ministry, archive or museum, with both the Freedom of Information Act, and more especially, with the Modernising Government legislation, which is putting a legal onus on organisations to manage, make accessible and archive their electronic documentation by 2004.

Spring 2001 Issue 37

- Editorial - Size Matters

- The Treatment of Mail on an Arm Guard from the Armoury of the Shah Shuja: Ethical Repair and in situ Documentation in Miniature

- Management of Large Objects at the Science Museum, Wroughton

- Digital Weightlifing and the Conservation of Large, Heavy Objects

- Four Terabytes and Counting

- Colour Changes for the V&A Facade

- Review of 'Gilding: Approaches to Treatment' UKIC Gilding Section Conference