Conservation Journal

Summer 2001 Issue 38

A Study Visit to Japan

It was dusk when we eventually left the workshop of the Ohsaka family, makers of paulownia wood boxes for scrolls and other art. I stepped into the traffic filled Tokyo street, clutching a bag of hand made wood nails and a box of Japanese sweets. It was my first experience of specialist craftsmen working in twenty-first century Tokyo and a fascinating introduction to the contrast between traditional and modern Japan.

My trip followed an interest in several Japanese methods of conservation and preservation; particularly the tradition of box making (kiri bako) and the construction of the cores for folding screens, sliding doors and drying boards (kari bari) all known as hone. In Japan and the Far East, wooden boxes are traditionally used for the storage of hanging scrolls, hand scrolls and other art objects, including books and household utensils. The fashioning of containers from paulownia wood (kiri-bako) has developed over centuries, the box-maker occupying a position within the multiple trade traditions that make up traditional Japanese arts and crafts.

My visit began in Tokyo under the stewardship of Dr Masamitsu Inaba, a materials specialist at the University of Fine Arts and Music in Tokyo. Dr Inaba spent several months in the V&A's Conservation Department. After a tour of the University conservation department and the Handa Kyuseido Oriental Painting Restoration Studio at the Tokyo National Museum we left with Mr Handa to visit the Ohsaka family workshop in the Shinjuko area of central Tokyo. We were greeted by Mr Ohsaka's wife who directed us to a small backroom workshop. Mr Ohsaka and his son were seated on the raised wood floor working at their benches.

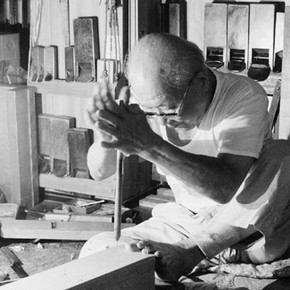

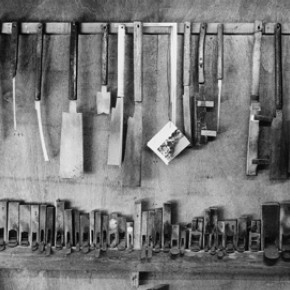

The room was lit by two bare bulbs suspended six inches from the floor and an ancient table saw was the only visible piece of machinery. Every available space was filled with timber and both men were surrounded by tools. Ohsaka senior is eighty-three years old and his son is fifty-eight. After our introductions they continued working on a hand scroll box for Mr Handa, including a futomaki (a kiri wood roller used to protect the scroll as it is rolled and unrolled). It was immediately obvious how specialised the whole construction was, from the choice of timber and tools; in particular the planes used to fashion the futomaki, wooden nails and specially prepared rice glue. After several hours we retired for tea with Mrs Ohsaka and her daughter in an anteroom between the workshop and shop front.

Having read his 1997 doctoral thesis 'Performance of Wooden Storage Cases in the Regulation of Relative Humidity Change', I was pleased to meet Nobuyuki Kamba, Head of Conservation at the Tokyo National Museum. His research concerned the buffering effects against fluctuations of the ambient relative humidity of several traditional storage cases, including a kiri bako and a lacquered outer box, (daisashi). It was particularly interesting to learn from Mr Kamba about the use of lacquer urushi as a barrier against fluctuations in humidity and temperature. We also touched on the traditional Japanese storage houses or kura.

The following day I met Dr Inaba at the moated entrance to Tokyo's Imperial Palace to visit the recently built Imperial Archive and Mausolea, in the grounds. Mr Kushige, chief librarian, explained that the new building replaced an older store and was built along traditional lines for the safe storage of fine art and archive materials. Approximately one million objects are stored in the five storey building which also houses offices, a reading room and conservation department.

The smell of camphor was overwhelming in the wood lined store rooms. A central passage ran the length of the room with shelf stacks at regular intervals. On the paulownia shelves were boxes, containers and cabinets of all shapes, sizes, age and design. At the end of each row of shelves were windows that, along with a large door were regularly opened to control temperature, humidity and air flow. The environmental conditions mirrored the findings of Mr Kamba, with only minor daily humidity fluctuations within seasonal changes. The visit ended with a tour of the conservation studio.

I spent a few days as a guest of Mr. Yasushi Yakoo, the managing director of the Masumi Corporation (suppliers of conservation materials). He arranged visits to his main kiri box supplier, Mr Yamazaki and his frame core maker, Mr Makino. Even with Mr Yakoo's sophisticated in-car navigation system the intricacies of the Tokyo highway system caused problems. After several telephone calls we were met by Mr Makino who had run down the lane to meet us, an impressive feat considering his seventy-four years.

His family has made the cores for folding screens, sliding doors and traditional Japanese frame for paintings (wa gaku) for generations. In one corner of the studio were several assembled frames and piles of cedar wood. Mr Yakoo and I sipped green tea brought by Mrs Makino while Mr Makino continued building a folding screen core. He explained the construction and we discussed shyaku, the traditional Japanese unit of measurement.

That afternoon we visited the home and workshop of Mr Kizou Yamazaki. Working with his son, Atsushi and another craftsman they supplied most of the boxes sold by the Masumi corporation. They predominately used American grown paulownia, but would also use home grown Aizu kiri, regarded as the best quality paulownia. Stacked outside the workshop were piles of wood left to season for several months. Mr Yamazaki kindly agreed to my staying with him and his family , allowing me the opportunity to study the construction of a kiri bako and futomaki in detail. I was overwhelmed by the help, indulgence and kindness that he and his family showed me; I will never forget a fantastic traditional Japanese breakfast shared with the extended Yamazaki family.

My ten days in Tokyo were over and after a weekend of sightseeing I boarded the bullet train bound for Kyoto for the next leg of my tour. My Kyoto, guide and Mr Yasushi Nakamura, a conservation officer at the Kyoto National Museum, arranged a meeting with the kiri box maker, Mr Yusai Maeda, as well as visits to the main conservation studios at the Kyoto National Museum, a tour of the museums storage rooms and a day with Mr Naohide Usami, at the Usami studio.

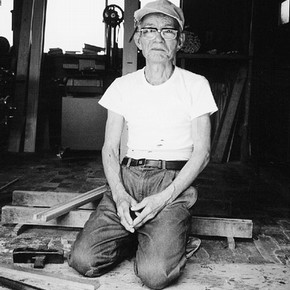

We met Mr Maeda, a highly regarded craftsman producing paulownia cabinets and boxes, at his home. He has been recognised by the Japanese Government for possessing special techniques for the conservation of cultural properties. He spoke of his place within the allied wood-working crafts and of the six generations of craftsmen in his family. He was very proud of his work and was happy to be known as a shakunin - the Japanese for craftsman.

Not far from the Maedas home was their two storey workshop. The ground floor was filled with wood and we climbed a narrow staircase, also crowded with paulownia, to the first floor workshop. Seated on the raised wood floor at the far end of the room, were Mr Maedas' younger brother, Yoshio Maeda, their cousin, Mr Motoo Furntani and Mr Maedas' son, Yasukazu. They were preparing wood for a large kendon bako (a cabinet for scroll boxes), finishing a kiri bako (scroll box) and sizing wood for another box. T

hey kindly agreed to my spending the week with them. It was fascinating working solely with hand tools and the quality of their work was exemplary. I now understood the Japanese craftsman and author Toshio Odate when he wrote, 'In short , the pride of the shokunin is the simultaneous achievement of skill and speed. One without the other is not shokunin', in Japanese Woodworking Tools: Their Spirit and Use . A highlight of my time at the workshop was a visit to a specialist tool shop.

As a guest of Mr Naohide Usami, son of the head of the Usami Shokadudo, I visited the workshop of the hone maker Mr Nanseido Takada in central Kyoto. Mr Takada's family have been making the cores for folding screens (byoubu) sliding door panels (fusuma) and the traditional Japanese painting frame (wa gaku) for generations. His grandfather's tools were displayed to the front of the workshop, many of them bespoke to the work and each one stamped with the family seal.

The large workshop was filled with daylight from overhead skylights. There were a couple of table saws and several workbenches on which stood long cherry wood boards used for planing the frames. Mr Takada's wife, Kumoko, an English teacher, translated for her husband. I was shown different styles of hone, the white cedar used for all hone and was also taught more about the traditional Japanese painting frame (wa gaku).

On my last day with Mr Nakamura we toured the storage area for lacquer ware at the Kyoto National Museum with the curator, Meiko Nagashima. Arranged in a series of glass fronted cedar cabinets were a fantastic collection of paulownia boxes of all shapes, sizes and finishes. Some were very fine lacquered boxes, often with three or four inner boxes and some were wrapped in silk or fine cloth. Ms Nagashima explained the significance of the inscriptions hako gaki, on the boxes. The provenance of the object is guaranteed by the name of the artist and subsequent owners.

We spoke about the traditional Japanese storage houses (kura), originally built in the grounds of temples, palaces and many domestic houses to store precious objects and papers. In contrast to the traditional use of wood for building, the kura is an earth construction, usually of two storeys, with a heavy outer door, an inner sliding door and a small window near the roof for ventilation. The most precious objects are generally stored on the second floor. Apparently it is often regarded as fortuitous if a snake takes up residence in the kura as they deter rats and other rodents and do not usually have a taste for wood and paper!

I thoroughly enjoyed my first visit to Japan, and it has proved to be invaluable to my research.

Acknowledgements:

Summer 2001 Issue 38

- Editorial - Desperately Seeking Eastern

- A Study Visit to Japan

- Review of MA Paper Conservation: Japanese prints

- A Chinese Figure in Unfired Clay: Technical Investigation and Conservation Treatment

- SIMS Analysis in Conservation Surface Studies

- Introduction to Chinese Traditional Book Making

- The Train stops at Gloucester Road - Futures and Values in Conservation

- The Resurrection of the Hereford Screen

- Printer Friendly Version