Conservation Journal

Spring 2002 Issue 40

Sustainability and precaution - Part 1

At a European Union research conference held in Strasbourg in December 2000, a European politician ended the proceedings with the prophesy that the key areas to watch in the near future would be 'sustainability' and 'the precautionary principle'. This was quite pleasing as I had just managed to work the precautionary principle into my last publication, and had started to think more closely about sustainability and conservation, having recently been given Jonathan Porritt's book Playing Safe: Science and the Environment.

Sustainability and the precautionary principle are separate concepts, but they are often linked together, most obviously in the area of the global environment. Sustainable development is the creation of new social and industrial activity 'that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs'1. The precautionary principle is usually invoked because the potential impact of a new technology could be so devastating that it is essential to prevent all possibility of damage. There may not be time to collect the necessary evidence of harm before the harm is irrevocably done. So it has been proposed that the approach to caution should not be dependent on absolute evidence of a hazard/harm relationship. The principle was incorporated into European law in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992:

'the absence of certainty, given our current scientific knowledge, should not delay the use of measures preventing a risk of large and irreversible damages to the environment, at an acceptable cost'2.

The world of museum conservation has its own traditional versions of sustainability and precaution. Museums give present-day visitors access to the collections while attempting to preserve these objects so that they can be used and enjoyed by future generations. Thus both museum collections and museum purpose are sustained. The control of museum lighting gives a good example of precaution. In order that light-sensitive objects continue to be available in the future, current exposure is restricted. Thought and action in the present prevents disappointment in the future. The conservator is protective of whole groups of objects, even where the extent of the dose/damage relationship is unknown.

Ecological 'conservation' pressure groups have been more aggressive and are more politically successful than the cultural heritage conservation lobby. The conservation of the moveable cultural heritage is not high on the political agenda. In the framing of national preservation policies, and in the descriptions of areas that will attract conservation research funding, the notions of 'sustainability' and 'the precautionary principle', borrowed from the ecological sector, have gained ground. For instance, 'sustainability' occurs in the call for applications to the European 5th Framework for Research. The Australian Natural Heritage Charter specifically 'acknowledges the principles of intergenerational equity, existence value, uncertainty and precaution'. 3

In many instances when people claim that their activities are sustainable, all they actually want to sustain is their own business, without too much thought for the maintenance of existing social structures or the future of the planet. Sustainability of business rarely involves leaving exploitable stock in the exact location and condition in which it was acquired. As an example, the 'positive contribution' proposed in the Statement of Commitment for Sustainable Tourism Development seems to imply more active intervention than a museum conservator would consider to constitute the 'conservation' of the target objects of tourism.

'We are committed to developing, operating and marketing tourism in a sustainable manner; that is, all forms of tourism which make a positive contribution to the natural and cultural environment, which generate benefits for the host communities, and which do not put at risk the future livelihood of local people.' 4

If we assume for the time being that museums are only concerned with ensuring their own sustainability, it is still not clear what needs to be sustained. By definition, all human-made artefacts are non-renewable as they are not self-replicating. A museum with a fixed collection can go on for a long time but is not infinitely sustainable because certain types of material will inevitably deteriorate beyond use or enjoyment. Thus the museum will eventually have to acquire new material to stay in business. One could not therefore criticise far thinking museum directors for acting as if their job was to oversee the continuation of the species 'museum object', rather than the stewardship of a permanent set of individuals.

Most museum objects that are kept indoors have lifetimes of several hundreds of years, which makes them permanent in comparison to museum directors or conservators. They appear permanent in comparison to maximum planning horizons that have been proposed for museum objects, which are in the order of two centuries or less.

By contrast, most living organisms have lifetimes in the low tens of years, often much less. They set about replacing themselves with virtually identical copies. A herd of zebra in the Serengeti National Park would look identical to one 10, 20 or even 100 years ago. Intellectually we would know that they were a different set of individuals. Although the molecular and gross physical structures of the zebras and their environment are the same now as they were in the past, the actual atoms that composed the first group could now be almost anywhere in the world. Scientifically a large number of analytical tests would show that the first group was identical to the second. Sustainability is seen as the continuation of appearance, behaviour and contextual relationships; summed up in the word 'significance'.

The significance of landscape is sustained through gross structural similarity over time and through the constant replacement of individual components with items of approximately the same shape, size and colour in approximately the same locations. No-one would complain that today's landscape was less 'authentic' than that of 50 years ago.

Without human interference many built structures have lifetimes that do not exceed the high tens or low hundreds of years. This is often because humans set out to change or destroy them. But inevitably the substance reacts chemically with the aggressive environment and the structure is subject to physical assault from vegetation, ground subsidence and seismic activity.

The inevitability of replacement is included in declarations about the conservation of historic sites. The fact that maintenance involves replacing original material and reproducing original intent means that it must be guided by feelings about authenticity. These considerations are expressed in the Declaration of San Antonio of 1996. The signatories assert:

'…the validity of using traditional techniques for their repair, especially when those techniques are still in use in the region, or when more sophisticated approaches would be economically prohibitive. We recognize that in certain types of heritage sites, such as cultural landscapes, the conservation of overall character and traditions, such as patterns, forms and spiritual value, may be more important than the conservation of the physical features of the site, and as such, may take precedence. Therefore, authenticity is a concept much larger than material integrity and the two concepts must not be assumed to be equivalent...' 5

Some sites are more authentic than others:

'...those valued as the concluded work of a single author or group of authors and whose original or early message has not been transformed. They are appreciated for their aesthetic value, or for their significance in commemorating persons and events important in the history of the community, the nation, or the world. In these sites, which are often recognized as monumental structures, the physical fabric requires the highest level of conservation in order to limit alterations to their character.'

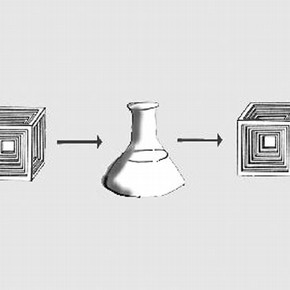

While thinking about these things during 2001 I gave a talk to members of the Royal Society for Chemistry. The title I had been given was 'Conservation - past and present' and the theme I chose was 'the more things change the more they stay the same'. I asked the audience to consider a thought experiment. A perfect crystal of common salt is dissolved in water and then a perfect salt crystal is grown from that solution (figure 1). There is no scientific test that could, in retrospect, prove that the second crystal was not the first. Intellectually one would know that they were not the same, but the appearance and the chemical and physical properties would not have changed. The significance would have been preserved. The experiment works because of the simplicity of the object and also because of its lack of association with a named human creator. It indicates that complexity and value are important factors in determining authenticity and significance.

The rate of decay also seems to be relevant. Where the lifetime of an artefact is inevitably short in comparison to that of a human, sustainability of significance is more likely to be judged by maintenance of intent, message and general appearance than by pedantic conservation of original arrays of atoms. Where the lifetime is long, the actual original material may be more important. Uniqueness, whether intrinsic in the complexity of the object or extrinsic in its association with an individual person, may lead to greater reverence for original material.

References

1 Our Common Future 'The Brundtland Report', The World Commission on Environment and

Development for the General Assembly of the United Nations. 1987, Oxford University Press

2 Maastricht Treaty, 1992.

3 Australian Natural Heritage Charter, Australian Committee for IUCN ( the World Conservation

Union), 1996.

4 Statement of commitment, Tour Operators Initiative for Sustainable Tourism Development.

5 Declaration of San Antonio.

Spring 2002 Issue 40

- Editorial

- Sustainability and precaution - Part 1

- People watching: Monitoring heritage hospitality functions in historic houses

- Ethical considerations in the treatment of a Tibetan sculpture

- Building models: Comparative swelling powers of organic solvents on oil paint and the cleaning of paintings

- Further applications of Raman microscopy in paper conservation

- Critical evaluation of laser cleaning of parchment documents

- Collaboration

- Printer friendly version