Conservation Journal

Autumn 2003 Issue 45

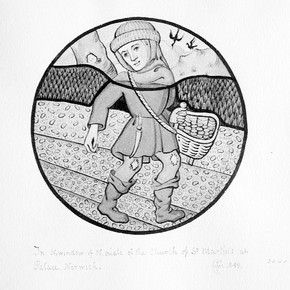

The October Labour

This article discusses the conservation of an early fifteenth century English stained glass roundel prior to its display in the 'Gothic: Art for England 1400- 1547' exhibition (Figure 1). It is one of only two stained glass objects from the V&A’s collection selected for the exhibition. Formerly located in the old parsonage at St Michael-at-Coslany, Norwich, this roundel is one of three from a set of Labours of the Months purchased by the Museum in 1931. It depicts a figure walking across a ploughed field scattering seeds taken from a wicker basket he is carrying by his side. Stylised trees and plants are in the background. The Labours of the Months was a common theme found in both manuscript illumination and roundel designs in England and on the Continent in the fifteenth century. Sowing seed was an agricultural labour of the peasantry representing the month of October.

Figure 1. October Labour before treatment. Museum no. C.134-1931. Photography by Sherrie Eatman (click image for larger version)

This leaded roundel measures 31.5 centimetres in diameter and is made of painted and stained glass. The details of the imagery were painted and fired onto both sides of the glass using traditional oxide paint. The various shades of yellow were obtained by painting and firing silver stain onto the back of the glass. While the glass is in good condition, there is paint loss throughout the roundel, with the worst affected areas being the red glass making up the border.

Upon visual examination, it was noted that the roundel had been releaded relatively recently (within the past 50 years or so) with a wider lead than it would have had originally. The roundel also contained several narrow leads that were added to repair broken glass. Of the four pieces of ‘foreign’ glass detected, the two pieces to the right of the figure’s head were considered particularly obtrusive. The painted and stained surface decoration on these later additions displays part of a quatrefoil and the letters ‘G’ and ‘N’ connected by a cord.

Past restoration treatments, which focused on repairing visible damage, may detract from an object’s appearance by obscuring the artist’s intended design. This is because original glass that was damaged or lost was often replaced with an arbitrary piece of glass taken from another window. Some of these restorations are not visually successful, particularly when the foreign glass is a different colour or has surface decoration that is a different colour or bears no similarity to the surrounding imagery that it is completing.

The principal objective of the conservation treatment was to restore the artist’s original intentions, which had become obscured by past interventions. Making the imagery more understandable would aid interpretation of the roundel while its overall appearance would benefit from the removal of repair leads and being releaded with a smaller width of came more suitable for the size of the roundel and delicacy of design.

Dealing with the distracting foreign glass required careful consideration of both ethical and aesthetic issues. After consultation with my supervisor and our departmental curator, it was agreed that in this instance there was a case for the removal of the most obtrusive stopgap because it comprised almost one quarter of the roundel yet its imagery was completely unrelated to the rest of the object. Research was undertaken in an attempt to determine the details of the missing imagery. The first step was to consult the acquisition file. It showed that the foreign glass had been added to the roundel before it was acquired by the Museum; therefore, there was no photographic evidence available on which to base the new replacement. However, a notation in the file did state that the roundel was “closely similar in design” to one reproduced by C.J.W.Winter in 1849 as being in the north window of the north aisle of the church of St Martin’s-at-Palace, Norwich (Figure 2). This drawing, which measures 10.2 centimetres in diameter, is in the Design Collection, Word and Image Department.

Figure 2. An October Labour from the church of StMartin’s-at-Palace, drawing, C.J.W.Winter, 1849. Museum no. 3440-8. Photography by Sherrie Eatman (click image for larger version)

Winter’s drawing, combined with the painted trace lines on the broken piece of original glass, provided enough evidence to allow for the completion of the figure’s hand, the basket handle and the seeded ground. Without this evidence, conservation options would have been limited to leaving the stopgap in place or inserting a toned blank which, while less distracting than the previous restoration, would not have extended the visual information that the object presented. Since the available evidence did not warrant the completion of the remainder of the missing background scenery, it was decided that the rest of the background would be toned to match the upper portion of the left side. Repeating the imagery from the left side of the roundel would have been too speculative, as would basing the new restoration solely on the drawing.

The two small pieces of foreign glass on either side of the figure’s head were not replaced since they were not as distracting as the larger stopgap. While the decision to leave this glass in place may seem inconsistent, in both cases the lack of evidence as to the original imagery meant that new replacements would have been too interpretative.

After the glass was removed from the leads it was cleaned using de-ionised water on cotton wool swabs. This was regarded as a safe method of cleaning since the paint appeared stable upon examination and spot cleaning under a microscope. The broken pieces of glass previously joined by repair leads were edge bonded with Hxtal NYL-1 epoxy resin. Small areas of missing glass were replaced by epoxy resin fills which were colour-matched to the original glass by adding Ciba-Geigy dyes to the resin.

The stopgap that was removed was replaced with a pale tinted antique glass that was cut to the correct shape. Next, traditional glass paint and silver stain were painted and fired onto the new piece of glass after samples of each were produced to ensure that the closest colour match with the original decoration was achieved in both transmitted and reflected light. The painting technique and stages of firing used by the original artist were studied closely so that they could be replicated faithfully. Finally, the new replacement was initialled, dated and recorded in the object’s treatment report. The foreign glass was preserved in the object’s studio file.

The new glass was attached to the original glass using the copper foil technique, which is easily reversed. Copper foil was used to join the glass instead of lead because it produces a strong joint and is less obtrusive visually. Furthermore, using a detectable method to join the pieces of glass gives viewers the opportunity to recognise that the restoration is not part of the original object, although non-specialists are unlikely to understand its significance.

Figure 3. October Labour after treatment. Photography by Sherrie Eatman (click image for larger version)

A rubbing of the leads which was made before the roundel was dismantled served as the working drawing while reglazing the roundel using a more narrow lead. When an object requires new leads they should be of the same profile and follow the same contours as the original when this can be established. In this instance, clues were taken from the size of the piece, the style of painting and how the glass was cut. Finally, a butyl mastic was inserted by hand between the lead and the glass to give the roundel strength.

A controversial yet justified decision was taken during the treatment of this object based on careful research and consultation with peers. The new piece of painted and stained glass and the more delicate leadwork has increased the legibility of the imagery without detracting from the appreciation of the whole object (Figure 3).

Autumn 2003 Issue 45

- Editorial

- Planning 'Gothic: Art for England 1400-1547'

- Climate monitoring of objects for the 'Gothic: Art for England' exhibition

- The October Labour

- Conservation of an English cadaver tomb

- Decision making: Technical information revealed

- V&A in the regions: Conservation Summer Schools at the University of Derby

- Elizabeth Martin 1947-2003

- News from RCA/V&A Conservation

- Printer Friendly Version of Journal 45