Conservation Journal

Spring 2004 Issue 46

CoSHH does work

As a normal part of the conservation process a risk assessment is undertaken before a conservation task is started. In the UK there is also the specific issue of the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (CoSHH) that legally impels the conservator to consider the ‘cradle to grave’ aspects of the chemicals in use. This law applies not only to those chemicals to be purchased and used during the conservation treatment but also to the residual chemicals in the objects themselves. The entry route to the body may be by inhalation of vapours or through the epidermis whilst handling or reshaping. This short contribution demonstrates that the CoSHH process has led to proper considerations of risk associated with the conservation and handling of felt hats shown to contain mercury salts. It also underlines the importance of understanding how the object was manufactured.

By no means a new phenomenon, the presence of mercury salts in felt hat manufacture has been known to present a health hazard to workers in the felt industry since the nineteenth century. It is generally held that the term ‘Mad as a Hatter ’derives from the Lewis Carroll tale published in 1865 as Alice in Wonderland where the Hatter at the Tea Party demonstrates the classic symptoms of mercury poisoning. More recently a 1994 paper follows up the Tuscany (Italy) compensation claims of 1,146 fur hat workers.

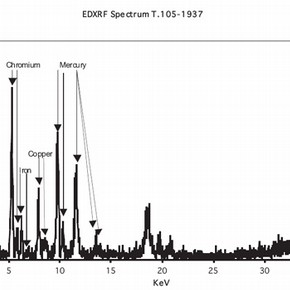

The potential for mercury salts to be contained in any of the hats in the V&A Collection was recognised early in the CoSHH risk assessment. A short pilot study was undertaken to verify the presence or absence of mercury by the use of energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDXRF) on a number of felt hats.

Different animal hairs have been used in the manufacture of hats and one of the most important was the beaver. The most desirable and expensive hats were made from beaver. Manufacture of felt relies on the property of animal fibres to become entangled when exposed to heat, moisture and intermittent mechanical pressure. This contribution is particularly concerned with the use of mercury salts to improve the felting process for beaver fur. This is known in the fur trade as carrotting. In the carrotting process metal salts were used in conjunction with a mineral acid or strong organic acid and usually hydrogen peroxide or some other oxidising agent was included. The authors have not located any modern texts on the use of metal salts. This is probably due to the switch away from the use of such metal salts due to their toxicity and environmental impact. A key early paper that describes the chemical processes and presents an early literature survey is that of Barr and Watt. It is evident that the industry very much wanted to get away from the use of mercury salts which was introduced in the mid 18th century. For a museum curator and conservator –the remnants of mercury from the carrotting process still remains a threat.

Figure 1. English black beaver hat, circa 1840. Museum no T.105-1937. Picture by Graham Martin (click image for larger version)

The most common damage to historic hats is crush damage and deformation due to poor storage, and the most frequently used treatment in the conservation of hats is the use of steam to relax and reshape them to remove these deformations. During this process, the hat is manipulated by hand to ease out the deformations and bring back the shape. When hats are embrittled and degrading, the steaming and manipulation process may need to be repeated several times as re-shaping can be a gradual and slow process.

The V&A has an estimated 100 hats that may be classed as felted fur hats. Up to 50% of this part of the collection is thought to contain mercury salts. At the Museum of London there are an estimated 31 hats that are classed as beaver and so may also contain mercury salts. It is impossible to estimate the size of other collections with any accuracy but in the UK alone there must be in excess of 1000 such hats.

As a short-term interim measure to minimise exposure of staff and visitors to mercury, the V&A devised a programme of isolating the hats by ‘bagging’. This has been undertaken until it was possible to use EDXRF to survey the collection. To enable continuing access to the collection a prime requisite was that the bag should be made of clear transparent material and self-adhesive chemical hazard symbols were attached as appropriate.The authors suggest that this is the minimum that can be undertaken to protect staff and visitors from potential mercury exposure. Gloves and a protective suit were worn during the bagging. For the bags, Mylar™ and self adhesive tape were used. Fit and proper disposal of the mercury contaminated gloves and other material should be arranged through local licensed chemical disposal contractors.

The nature of the EDXRF analysis has considerable advantages in that the technique is non-destructive but it is difficult to quantify the levels of mercury in the felt. In order to determine these levels a specialist laboratory was contracted to undertake destructive analysis on a sacrificial hat obtained specially for these purposes.The Environmental Impact Analysis Group at the University of Derby 1 have the necessary expertise and equipment to undertake this work, that has shown that the average mercury content of this hat was 1.1% w/w 2 .

A literature study had identified that the traditional conservation process of steaming the felt hat in order to re-shape could lead to the loss of mercury in the fur 3 . One of the sources reported that there was a loss of between 7% and 9% by weight of mercury when fur is subjected to a temperature of 105°C 3 . The use of steam to treat hats may give rise to exposure of the conservator to mercury, and appropriate safety measures must be employed. To test this, under carefully controlled and agreed conditions, one half of a sacrificial hat was subjected to steaming as would be usual in conservation processes. Typically this is five to ten minutes of steam and hand manipulation. No significant difference between the steamed and unsteamed half of the hat could be found. Also, occupational hygiene monitoring of the air that the conservator was breathing indicated a mercury concentration of 0.7 gm 3 where occupational exposure standards for mercury are 25 gm 3 - 4 . Note that entry to the body via skin contact has been excluded from consideration in this investigation as gloves were worn.

The authors have been aware of this issue for over ten years. The potential for arsenic, mercury, cadmium or other substances exists. Exposure of staff and visitors to other harmful chemicals must be treated with the utmost concern.

The proper use of risk assessments and CoSHH has identified the hazard and given staff a tool to manage the issues involved.

This article is an updated summary of a paper presented at the Conservation Science CS2002 conference, Edinburgh 2002 5

References

1 Environmental Impact Analysis Group, Research Centre Director: Dr N Hudson, University of Derby, Kedleston Road, Derby DE22 1GB.n.f.c.hudson@derby.ac.uk +44 (0)1332 591719

2 Environmental Impact Analysis Group, University of Derby, TEST REPORT No 8395

3 Wood, M. and Haigh, D., 'A Comparison of the Belgian and BHAFRA Methods for Estimating the Amount of Mercury Present in Carrotted Fur', a technical report of the British Hat and Allied Feltmakers Research Association (BHAFRA) now defunct. The archives are held by the Hat Works –The Museum of Hatting, Stockport, UK. BHAFRA Library report: 35, page 6, 4 November 1955

4 Evans, R, Report from Aon Health Solutions dated 20 June 2003

5 Martin G. and Kite M., 'Conservator Safety - Mercury in Felt Hats', Proceedings of Conservation Science 2002 Conference, Edinburgh May 22 - 24, page 177-181, Archetype Publications, London ISBN 1-873132-88-3, edited by J. Townsend, K. Eremin and A. Adriaens, 2003.

Spring 2004 Issue 46

- Editorial

- The new paintings galleries

- The cleaning of two paintings by Turner

- The conservation of three gilded frames for the new paintings galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum

- An introduction to gemmology

- Restructuring of the Department

- Staff development in conservation issues

- CoSHH does work

- The OCEAN project at the V&A

- An Indian painting workshop led by Shammi Bannu

- Printer friendly version