Conservation Journal

Summer 2004 Issue 47

RCA/V&A Conservation - do professional conservators make a contribution?

Introduction

In public statements on the value of the joint Royal College of Art and Victoria & Albert Museum Conservation (RCA/V&A Conservation) MA programme, great emphasis is placed on a number of defining characteristics, including

-

the postgraduate experience

-

practical training in a working conservation environment allied with high quality academic learning

-

a particular value in the partnership, association and collaboration with a variety of museums, educational institutions and heritage organisations

-

specialist programmes of study

Frequently we claim an overall uniqueness - and hope that no other course will point out that we are not so special.

One claim for the learning experience we deliver that might be taken for granted is that the involvement of the conservation profession is necessarily a major advantage. This is seen as so obvious that we rarely, if ever, make a case for this. We may be presumptuous, never testing the claim, or unduly humble in understating our case. Perhaps we should consider what it is that the profession brings, if anything, to our education and training in conservation and what justifies a claim that this makes RCA/V&A Conservation unique - and advantageously unique - in the postgraduate education field.

Professional Practitioners

The Royal College of Art places great store in the fact that its students are taught by practitioners in art, design, research and, in our case, conservation. In this way, graduates are seen to be in touch with their likely profession throughout the postgraduate experience they receive and benefit from an involvement in current practice within the profession. As a consequence, employment prospects are good and this is reflected in available figures for graduate destinations. While Vehicle Design graduates may be almost 100% employed within their profession, Conservation is not far behind, and this seems a reasonable measure of the extent to which the College is achieving the terms of its charter.

'The objects of the College are to advance learning, knowledge and professional competence particularly in the field of fine arts, in the principles and practice of art and design in their relation to industrial and commercial processes and social developments and other subjects relating thereto through teaching, research and collaboration with industry and commerce'.1

For RCA/V&A Conservation, our industry is the world of museums and heritage, cultural values and valued objects. The training and educating of our students within the industry enables them to develop skills completely relevant to future employment in the industry. Even when in those situations of contracting staff numbers, shrinking resources, and "re-organisations", our students are learning to operate within the realities of the conservation world - although we would not wish to make too much of a virtue of this!

Recently Design Review reported on the shift in design education away from the practical to the theoretical, away from its vocational past 2 . Dan Fern, the RCA's Head of the School of Communication and Design, noted the difficulty in producing graduates for the design and art direction industry when teaching is switched from "the visual to the cerebral" and pointed out that "Education is failing [design] industry by not producing people who can work within it comfortably" but it is producing "people who can work within it awkwardly". The article concludes that if the industry wants the people it needs for the future, "it must take an active role in training the next generation."

RCA/V&A Conservation's MA Programme has been likened to an apprenticeship in a craft. We expect our students to graduate both with mastery of their subject and to fit within the profession. That is not to say that we expect them to be passive. We believe that we train them to be independent decision-makers and, perhaps, their comfort comes from being awkward enough to shift the profession a little in their direction.

The role of the Profession

Commenting on the profession in conservation, Stan Lester, consultant in professional and work-related development, notes, "Occupations claiming what they regard as professional status frequently focus on the attributes seen to define a profession as opposed to a non-professional occupation. One of the attractions of this static or trait approach to professions is that it offers a relatively simple means of deciding how much an occupation has progressed towards becoming a profession, at least in the terms of the model being used" 3 .

Lester suggests that this static approach, the professional standing back and codifying the state they have attained, fails to acknowledge the changing environment in which professions operate, but it also fails to acknowledge that professions can generate the developmental processes which move this environment forward.

In another paper Lester 4 defines and classifies two models of profession. In Model A, professions are "more or less standard occupations for which the title reveals much about the job content". In Model B, "professionals are not necessarily part of any recognised profession", and their professionality [being a professional], is based on "a portfolio of learningful activity individual to the practitioner, integrated by common personal values and beliefs". In Lester's paradigms 'technical' and 'logical' (Model A) are distinguished from 'creative' and 'interpretive' (Model B). Model A's 'solving problems; applying knowledge competently and rationally' contrasts with Model B's 'understanding problematic situations and resolving conflicts of value'. And an 'initial development concerned with acquiring knowledge, developing competence and enculturation into the profession's value system' (Model A) is juxtaposed to 'ongoing learning and practice through reflective practice, critical enquiry and creative synthesis and action' (Model B).

The aims of RCA/V&A Conservation seem to encompass the attributes of professionality described by both models. MA students are prepared for the profession through the development of professionality, aiming to satisfy both occupational standards and personal goals. As befits a postgraduate course, these personal goals, and accompanying values and beliefs, are likely to be on show. This is also appropriate since much about conservation is highly personal and directed by individuals' values. While the proliferation of codes of conduct and the organisation of professional bodies can be viewed as a measure of the commonality of the field, the need to erect common markers is also indicative of the diversity of opinion and practice out there. While we teach good practice, we also teach that decisions in conservation are dependent on circumstance, and a large element of the circumstance is the person making the decision. Confidence in decision-making, and the ability to justify that confidence, is a major part of a good student's development.

RCA/V&A Conservation's approach is not to position us, and our students, somewhere on the spectrum between the two models of professionality but to satisfy both. We are delivering professionals whose professionalism advances the profession!

Personal influence

The conservation profession does have an influence on the MA course we deliver but this tends to be more indirect than direct. The conservation profession generates its view of desirable and undesirable developments, erects, alters and influences organisational structures, and projects an image to promote its own sustainability. As such it creates part of the environment within which we educate.

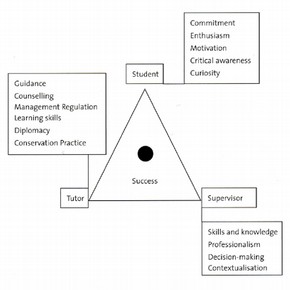

Figure 1. Some of the attributes that each member of a student’s team contributes to a successful learning experience. (click image for larger version)

Critically, and more accurately recognising their input, it is the direct interaction with the individual, specialist supervisor that is likely to have most influence on the outcome of a student's course of study and the profession is probably one step removed from this intimate relationship, the wider, collective, picture filtering through the actions of individuals. And while the conservation profession impinges indirectly on our student experience through individual supervising conservators, the direct experience of supervising our students hopefully has benefits for the profession. In the relationship between students and the supervising conservator, the development is unlikely to be one-sided.

The process of supervising is a dynamic process through which the professional is likely to critically appraise and assess their own abilities. Few of our supervisors or course staff do not, at some point, wonder if they are doing the right thing as they develop a syllabus, make an assessment or give advice. The conservator engaged in education and training is providing a particular service to their profession - and the profession benefits in two ways. It benefits from the introduction of qualified conservators and from the further development of collaborating professionals. In a sense, the profession develops through the medium of the successful student.

It is easy to become too lyrical about the dynamics that operate within our MA programme, as if student, specialist supervisor and course team member move only in happy unison through the course of study. This is not a perfect science - or even a magical art. While we attempt to guide, encourage, and support the relationship between student and specialist supervisor, this three-cornered relationship only operates through the recognition and acceptance by each partner that our respective positions are negotiable and shifting.

The student brings a desire and commitment to learn, and a sense of the direction in which they wish their particular study to move. The course team offer a format and formula for learning, a set of academic standards and regulation, and a commitment to a satisfying postgraduate experience. And the specialist supervisor delivers training in practical skills, offers specialist knowledge and academic guidance, and contributes to an assessment of progress measured against the state of the profession, the aims of the course and the contribution the student makes to their own development (Figure. 1).

At any time the extent which each contributor delivers part of the experience to may change. As the student's enthusiasm wanes, it may be necessary for the others to offer more encouragement. Where the supervisor's particular element of skills or knowledge may be weak, others may be recruited to support this this. And where a tutor's professional expertise may lie in a field other than the student's specialism, it may require both the student and the supervisor to be more pro-active in defining suitable tasks and assignments. This triangular relationship is between people and, while regulation and professionalism are elements of the formal framework to ensure compliance with standards, the distance between the individuals will shift as external influences of health, employment, finance and other relationships intrude (Figure. 2).

Although the distance between the three parties can be elastic, there are limits to how far they can stretch before they lose sight of the central aim - a successful learning experience for the student. This distinguishes the position of our students from that of other unpaid museum workers, such as interns. In the partnership between student and College there are measurable - and audited - standards of success.

Teachers and trainers

One of the aims of RCA/V&A Conservation is to provide the skills, which might be considered as training, and the knowledge, which might be considered academic teaching. However, the distinction between these two attributes is an everyday obstacle in discussions of what we do. RCA/V&A Conservation delivers an experience of combined skills and knowledge, with the student spending approximately 60% of their time working in their host studio or laboratory.

Attempts to refer to the "classroom", common curriculum of the MA course as the "academic" element founder for two reasons. Firstly, because our "classroom" curriculum serves only as a guide to the deeper learning we expect our students to embrace under their own direction. And, secondly, because much that is "academic" learning in conservation arises in the process of and as a result of practical studio experience.

Reference to the studio or laboratory element in the MA course as the reservoir of practice also comes adrift. While most practical skill is learned in the studio or laboratory, we also provide specific events, such as an environmental monitoring project and a risk recognition and assessment exercise, which deliver skills outside of the studio.

The conundrum in the relationship between education, as the transfer of knowledge, versus training, as the transfer of skills, - is a well-rehearsed debate 5 . Kuban 6, addressing the needs for education and training for emergency services, points out that, "Both training and education provide individuals an opportunity for growth, and enhance their capacity to perform their professional duties. The key point here is that both are required on an on-going basis to stimulate growth!". The UK's Ambulance Service Association 7 noted that, "The concentration within paramedic training programmes on practical skills is considered to have underemphasised the relationship between practice and theory and therefore to have failed to produce success".

Just as false as the assumption that conservation skills are only learned in studio practice, is the assumption that the professional conservator engaged in the supervision of a student, is only concerned with practical skills. There is much knowledge-based learning in conservation practice and the skills learned are not only those that require physical action.

For the student, the skills developed within practice should go far beyond manual dexterity. As well as knowing how to do something, they are trained in the selection and application of what to do, and - crucially - to do all of this within the context of a working environment. This is a skill that can only be learned within practice, from practitioners. This experiential element is what professional conservators can deliver in their supervision of studio and laboratory practice - an appropriate process of enquiry and the knowledge of applicability. It is possible to learn practical conservation skills within a classroom, but learning through abstraction will not help to develop professionalism. The skills that our studio and laboratory supervisors deliver are the practical skills of the conservation profession. These include

-

assimilating and selecting information

-

juggling several tasks at once

-

communicating work with other professionals

-

interacting with colleagues

-

making decisions within a context

-

recognising competing values and compromising

-

negotiating a path through the vagaries of working life

These are also the skills of any profession.

Conclusion

RCA/V&A Conservation is unusual in that it delivers an experience of the conservation profession. The professional conservation practitioners involved in the intimate supervision of the learning experience mediate between the organised conservation profession and the new, developing, conservation professional. Through a focus on individual development and contextualised learning, we merge the boundaries between practice and theory. Perhaps what we are delivering is not so much a Master's degree after studying conservation, but a Master's degree arising from study within conservation. MA(RCA) is more than a subject qualification.

References

1 Charter of Incorporation of the Royal College of Art, 28 July 1967

2 Burgoyne, P., Theory or Practice. Design Review, 2004pp 41-43.

3 Lester, S., Becoming a profession: conservation in the United Kingdom. Journal of the Society of Archivists, 23(1), 2002, pp 87-94

4 Lester, S., On professionalism and professionality. September, 1994, http://devmts.org.uk/publications.htm

5 Lester, S., Overcoming the Education - Training Divide: the case of professional development. Redland Papers, Autumn, 1996, pp1-8

6 Kuban, R., Dialogue On Crisis. Canadian Emergency News, 24(3), 2001

7 Newton, A., Elliott, S., and Howson, A., A Discussion Paper on the future of education, training and development for emergency ambulance staff. Ambulance Education & Training Advisory Group of the ASA, 2003, http://www.asa.uk.net

Summer 2004 Issue 47

- Editorial

- Conservation Department away day - December 2003

- Future challenges for RCA/V&A conservation

- RCA/V&A Conservation - do professional conservators make a contribution?

- Traditional Japanese lacquer workshop: Summer 2003

- The Internship and Placement Programme at the V&A Conservation Department

- LightCheck®: A new tool in preventive conservation

- RCA/V&A Conservation study trip, March 2004: Lisbon, Portugal

- Printer friendly version