Conservation Journal

Autumn 2008 Issue 56

Conservation of a ninth-century bowl from Iraq

The small ninth-century bowl from Basra (Circ.175-1926) in Figure 1 marks two significant developments in ceramic history. In an attempt to imitate the much admired fine white porcelains that were being imported from China, potters in Iraq developed a lead glaze whitened and opacified with tin oxide to make their local yellowish earthenwares look white. This new technology would spread throughout the Islamic world and eventually Europe. In addition, the Iraqi potters introduced the use of cobalt oxide, a blue colourant, on ceramic surfaces for the first time in history. They used this locally available mineral to decorate their newly-developed white glazes. Iraqi traders subsequently exported their ceramics and the blue colourant to China where Chinese potters started using it to copy the Iraqi designs on their porcelains. This marked the beginning of the first blue and white ceramics still popular today.

Because of these technological milestones, the bowl will feature in the touring exhibition Masterpieces in Ceramics from the V&A, which will travel worldwide during 2008-9. The exhibition will show 120 highlights from the V&A collection representing a timeline of major worldwide developments in ceramic history. On their return, the objects will form a prominent part of the permanent display within the V&A's newly refurbished Ceramic galleries. The first six galleries open to the public in September 2009 as part of the ambitious V&A FuturePlan, a long-term development scheme, which aims to radically update the display of the collections.

On examination of the bowl, significant questions were raised concerning its stability and interpretation. It had broken in about forty-one pieces and was subsequently bonded together. Any losses were then filled and crudely overpainted. Five shards probably once belonged to another object as they had originally been undecorated and differed slightly in thickness, curvature, colour and surface condition. Introducing foreign shards during restoration is not unusual on Islamic wares, and is known to have been practised since the early seventeenth century.1 Many of the old bonds were structurally unstable, which put the object at risk of further damage.

Figure 1. The bowl during treatment (Photography by Hanneke Ramakers) (click image for larger version

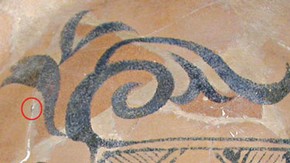

The ill-fitting replacement pieces and original misaligned shards caused the bowl to have a very irregular surface. An attempt had been made to even out the irregularities with a white filler similar to plaster of Paris. The filler was excessive and needlessly obscuring the original glaze. It had also rubbed into many tiny pinholes in the degraded glaze concentrated on the back of the bowl, creating a distracting white bloom over the surface. In addition it soon became clear that the missing floral design on the front was repainted in a manner that did not match the original (Figure 1). After removing some of the old restoration material, a small area of the original blue decoration emerged, revealing the true shape of the pattern (Figure 2).

To stabilise the structure of the bowl several options were considered of which two seemed suitable. One option was to dismantle and re-bond the bowl because of the relative weakness caused by misaligned shards and failing adhesive. The other option was to stabilise the bowl's structure by reinforcing it through consolidation of the old joins. Dismantling, however, can introduce the risk of staining in this type of very porous ceramic. Furthermore, the structural weakness of the bowl was only concentrated along a few break lines rather than the whole. For these reasons, consolidation was chosen rather than re-bonding. As a result, the replacement shards were retained, although they were of a slightly different shape to the original. The shards support the structure of the bowl well and are of historic interest. ParaloidTM B-72 (ethyl methacrylate methyl acrylate copolymer) in acetone was chosen as a consolidant. For narrow cracks a solution of around 5% was used, while wider cracks required a more viscous solution of up to 20%. Subsequently old excess filling material was softened with de-ionised water and later removed with a scalpel blade.

Figure 2. Detail from bowl during cleaning showing the incorrectly painted blue design, the circle indicates the small area of the original blue decoration that emerged after removing the old restoration material (Photography by Hanneke Ramakers) (click image for larger version)

A strange effect was observed in the glaze that had been covered by the old restoration materials. The glaze that emerged from underneath had a lighter colour. All the shards, including the replacement ones, revealed this. At first it was assumed the colour difference was due to white residue from the old restoration material. After examination under a microscope (x20) it became clear the surface was truly clean and the glaze itself had a lighter hue. The reason for this remains unclear and requires further research.

The next challenge was to reduce the amount of white filler caught in the pinholes. Dry cleaning methods routinely used on ceramic surfaces did not make a noticeable difference. An alternative approach was adopted using an airbrush. An instrument originally devised for painting, it has also been used to retouch restored areas on ceramic objects. The airbrush uses compressed air to force paint through a nozzle resulting in a fine spray. An effective cleaning method was developed using the airbrush with de-ionised water instead of paint. The filler was softened by dampening it with de-ionised water. Then an airbrush was filled with de-ionised water and the force of the spray was used to push the filler out of the pinholes. The surrounding area was covered with an absorbent tissue paper to avoid any water being absorbed into the body through the breaks and the glaze was checked regularly to confirm no damage was caused by the pressure of the water. This method worked very well as the majority of the filler shifted and the appearance improved considerably.

Chips along break-lines were filled with Modostuc® paste (calcium carbonate based filler with smaller amounts of barium sulphate in a poly (vinyl acetate) copolymer binder). The incorrectly painted blue design was removed and reinterpreted using the existing pattern as a guide. The design is not only attractive, but it is also known to have been reproduced on Chinese porcelain, demonstrating the influence of trade. The viewer can now appreciate the true intention of the potter. All retouching was done with Golden® Acrylic Polymer Varnish with UVLS (acrylic/styrene copolymer solution) mixed with Golden® Fluid Acrylics, Golden® Airbrush Colors and dry artist's pigments. Fumed silica (amorphous silicon dioxide, Gasil® 23D) was used as a matting agent.

The aim of the conservation was to prevent further damage from occurring and ensure the correct interpretation of the bowl. The strengthening of the old joins has made the bowl structurally sound, it is now safe to handle and travel with the exhibition. The interpretation has been improved by correcting the design to a truthful representation and reducing the white bloom on the back. As a result, it will feature as one of 120 highlights of the collection in the touring exhibition Masterpieces in Ceramics from the V&A.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Mariam Rosser-Owen, Curator in the Middle Eastern Section, for her assistance.

Materials

Golden® Artist Colors, Inc., www.goldenpaints.com

Modostuc® paste, Plasveroi International, www.plasveroi.it

Reference

1. Koob, S.P., 'Restoration skill or deceit: manufactured replacement fragments on a Seljuk lustre-glazed ewer', The Conservation of Glass and Ceramics; Research, Practice and Training Ed. Norman H. Tennent, James and James (Science Publishers) Ltd., (London, 1999), p.157

Autumn 2008 Issue 56

- Editorial Comment - Conservation Journal 56

- Displaying stained glass in a museum

- Resources vs access: meeting the challenge

- Costume cleaning conundrums

- Digital Killed the Analogue Star! Care of V&A collection based carrier and machine assisted media

- Observations on the causes of flaking in East Asian lacquer structures

- Practical ethics

- Mount making for the Medieval & Renaissance exhibition tour

- SurveNIR project: non-destructive characterisation of historical paper

- The reconstruction of the materials and techniques of Nicholas Hilliard’s portrait miniatures

- Conservation of a ninth-century bowl from Iraq

- Renaissance painted cassoni

- A forthcoming technical publication of Renaissance frames at the V&A

- Conservation webs

- RCA/V&A Conservation: In-post MA for conservation professionals

- Printer friendly version