Conservation Journal

Autumn 2013 Issue 61

Historic Repairs

Hanneke Ramakers

Ceramics, Glass and Related Materials Conservator

Figure 1. Tin-glazed milk pan with rivet repair, Adrianus Kocx, ‘The Greek A’, Delft, early 1690s, Diam. 47.4 cm, Photography by Hanneke Ramakers Given by Louis Gautier. Museum no. C.384-1926 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Conservators come across old repairs on a regular basis while examining the stability of objects. To enable safe display and preserve objects for future generations, old repairs often need to be replaced or improved Over time they tend to fail in their original purpose of giving structural support or improving the visual coherence of an object, however, occasionally, they add value to the object by giving information about its history. In preparation for the Europe 1600-1800 Galleries, due to open in December 2014, the pros and cons of keeping an interesting repair on a tin-glazed earthenware milk pan (Figure 1) had to be considered. This sparked further interest in how conservators of different disciplines approached old repairs. This article illustrates four examples from the V&A Collection.

Metal rivets have been used to join together the broken pieces of an earthenware milk pan (Figure 1). The rivets still perform their original function but are outdated as a technique, having been replaced by synthetic adhesives that were not available at the time of the original repair. As rivets are a visible repair they may be considered disfiguring. They had been painted white in an attempt to conceal them but the paint has since aged and yellowed. There is some evidence that historically, rivets were painted over as part of the repair.1 Retaining the rivets posed no risk to the object and their location means they are not immediately obvious. The rivets are well made and display the expertise of the repairer while also demonstrating the best skills and materials available at the time. The owner of the milk pan considered the object valuable enough to have it repaired rather than replaced. Preserving the rivets gives information about the cultural significance of the object at a certain point in time, without reducing the object’s aesthetic purpose.

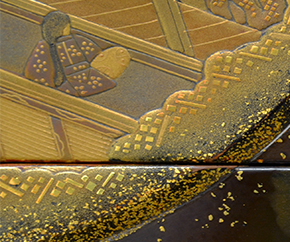

A second example of a repair that adds information to an object is found on a tiered lacquered wood box for serving food (Figure 2). The box was made in Japan for the Paris Universal Exposition in 1867 and acquired by the Museum two years later. It is very unusual to find a repair to a lacquer object that utilises Asian lacquer because the necessary skills and materials were not readily available in late nineteenth-century Europe. Initially, the fill would have been invisible but now it stands out due to a colour change over time - a phenomenon typically difficult to predict. The halo of uneven gloss around the repair - damage caused by the restorer abrading the original surface when levelling the fill - is also distracting. However, the damage gives information about the object’s manufacturing technique using Asian lacquer known as ‘urushi’, as it clearly shows the build up of the translucent layers. The ‘urushi’ fill is a durable repair because it has expanded and contracted in unison with the surrounding material, unlike most Western repair materials. Additionally, its removal would cause significant damage to the adjacent original lacquer. The added value of this distinctly Japanese restoration favours leaving it undisturbed.

Figure 2. Tiered box for serving food depicting the Tale of Genji with Japanese lacquer repair (822:1 to 8-1869) H 30.5 cm, Photography by Hanneke Ramakers © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Figure 3. Tapestry showing the arms of the Family of Giovio with painted canvas repairs, Flanders (Belgium), mid-sixteenth century (256-1895) W 627 cm, Photography by Susana Fajardo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Likewise, the reverse of a verdure tapestry, woven in dyed wool and silk, reveals stitched patches of skilfully-painted canvas which recreate areas of loss and add structural strength (Figure 3). The exact age of these repairs is unknown but records indicate they are over 50 years old. Today, significant areas of loss may be infilled with fabric patches dyed to blend with the surrounding area. Smaller areas may be re-warped, and the weft loss can be indicated with spaced couching of matching colour. While the painted canvas in-fills greatly improve the visual coherence of the tapestry, there was a risk of damage from uneven tensions created by some of the stitched patches so they were removed temporarily to allow the surrounding areas to be strengthened. The patches were then returned to their original location as evidence of the repairs carried out at a particular time.

Figure 4. Stained glass panel with a stopgap depicting a pumpkin, Erfurt Cathedral, Germany, around 1375 (C.200-1912) H 71 cm, Photography by Sherrie Eatman © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A traditional leaded stained glass panel (Figure 4) had a broken section of glass in the top left corner, making safe handling and display extremely difficult. Based on the original glazing scheme, this section should have depicted the continuation of a palm; instead, it depicts a pumpkin. This is a ‘stopgap’ - a common historical repair where the craftsman inserts a piece of glass chosen from the studio’s scrap box. Nowadays a loss would be filled with glass painted to match the original design. If the original imagery is unknown, a toned blank would be inserted. A stopgap could be considered misleading because it does not represent the intent of the maker. However, the panel came into the Museum with the stopgap in place and it is a well-established part of its history. It has a good colour match within the existing colour scheme and does not detract significantly from the interpretation of the scene. There is no evidence revealing the exact original design, so a new restoration would be an interpretation. Lastly, it is amusing: a charming addition showing what happens to panels throughout history. The stopgap was restored and is still part of the panel.

When deciding if it is appropriate to retain old repairs the issues are similar across conservation disciplines. If the repair causes harm and prevents further treatment, it may be necessary to remove it. If it is stable, retaining it may be the best available use of resources. An acceptance of the appearance amongst the stakeholders is also taken into account. If an old repair displays a high level of skill, fulfils its original purpose and adds information, such as social significance, this will contribute to its preservation. These decisions can be complex, particularly the subjective issue of when the repair becomes ‘part of the object’. Sharing examples across disciplines can give an insight into different approaches and help the decision-making process.

Reference

1. Garachon, Isabelle. ‘Old repairs of China and Glass’, The Rijksmuseum Bulletin, 58, 2010, p.39.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Sherrie Eatman, Susana Fajardo and Shayne Rivers for describing their decision-making processes on these repairs.

Autumn 2013 Issue 61

- Editorial

- The V&A’s Historic Stained Glass Windows

- An Investigation into the History of a Damascened Iron Games Table

- Collaboration with the Hirayama Studio, British Museum

- An ‘Exploded’ Replica of a Commode

- Smoke and Mirrors: What's holding Hollywood Costume up?

- Developing a Strategy for Dealing with Plastics in the Collections of the V&A

- Computer Love

- The Plaster Cast Courts Project: an introduction

- Historic Repairs

- Textile Sample Books Move

- Research on Paintings – A New Display

- David Garrick’s Tea Service