V&A Online Journal

Issue No. 3 Spring 2011

ISSN 2043-667X

Review: Not quite Vegemite: An architectural resistance to the icon

Freelance Writer

‘Is there an architecture of resistance that stands in the face of commercial globalisation: that rejects the iconic image; that celebrates the spirit of individual place?’

These were the questions that were asked at Sustaining Identity: Symposium II, held at the V&A Museum in November 2009. This was the second in a series of events organised by the V&A, the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) and architect’s Arup Associates. Sustainability in architecture usually means designing environmentally friendly buildings. The cultural organisation UNESCO, however, has coined the term ‘whole life sustainability', to reflect their concern that architecture should ‘incorporate local identity into the design process'. They argue that the idea of sustainable architecture should be widened to include the way a building relates to its social, cultural and geographic situation.

At this event, major architects from around the world - the USA, Chile, South Africa, Australia, Finland, the UK, Spain, India - provided case studies of architecture that related in various ways to their local contexts. The key-note speaker, Finish architect and author, Juhani Pallasmaa, used the work of Guy Debord to criticise much of today’s architecture as ‘mere representation'. In a recent essay, he writes: ‘Today’s fashionable architecture seeks to seduce our eye but it rarely contributes to the integrity and meaning of its setting'. He gives no specific examples of buildings he dislikes, but does give examples of those that he thinks successfully relate to their context. These include Louis Kahn’s National Assembly Building, Bangladesh (1983) and Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium, Finland (1933).

Distinguished Indian architect, Charles Correa, gave a stimulating talk entitled ‘Architecture is not a Moveable Feast', which celebrated architecture ‘rooted in the soil in which it stands, in the climate, in the materials and the technology'. He argued that place is more important for architecture than for any other art form, and gave Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park houses, Chicago, as the supreme example of an architecture rooted in a particular place. Drawing on the work of British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, he emphasised the importance of using the space between buildings, pointing out that people will occupy these spaces and make them their own. His work is inextricably linked to the climate of India, which has led him to develop the concept of ‘open-to-the-sky space'. The hot humid climate of India makes it more comfortable to be outside in the evenings and early mornings so that the edge of the street becomes an extension of the house.

Learning from the urban lifestyle of India, Correa has conceptualised a hierarchy of spaces: the private space of the home, transitional space where private meets public (e.g. the doorstep), the local neighbourhood space (e.g. the communal water tap) and the wider urban space of the city. This idea is manifested in his architecture, such as the low-income Incremental Housing at Belapur, New Bombay (1983-85). Clusters of seven houses are arranged around a small courtyard, and further clusters of seven houses are added on to this group to form a community based around a larger outside space.

Correa’s Kanchanjunga, Bombay (1970-83), a 28-storey tower block of luxury flats in a city of poverty, may not seem to fit into the spirit of sustaining local identities (fig. 1). But it is a building again influenced by Correa’s use of space in response to the climate and informed by vernacular architecture. Orientated east-west, the block captures the prevailing sea breezes and best views (the sea and harbour), but this also means exposure to scorching sun and monsoons. To counteract this, the main living areas are located in the centre of the apartment, protecting them from direct heat, and cooled by breezes entering via the double-height garden veranda. Although the Indian colonial bungalow is an important influence on Correa’s work, he dislikes the block’s nick-name of ‘Bungalows in the Sky'.

Figure 2 - Glenburn House, Sean Godsell, Victoria, Australia, 2004-07. © Earl Carter, photograph courtesy of Sean Godsell

An Australian outback house made of concrete and an oxidised steel grid, commonly used for industrial walkways, may not appear to relate in any way to its local context. But the Glenburn House, Victoria (2004-07), is also heavily influenced by its local climate and vernacular architecture (fig. 2).

As architect, Sean Godsell, explained in his talk, ‘The Bush Mechanic', here too the veranda (drawn this time from early Australian houses alongside some Japanese influences) is reinvented so that the house plan becomes, in effect, an ‘abstract veranda'. The house is a sequence of spaces – car parking, utility room, a flywire covered breezeway and living and sleeping blocks – that respond logically to the harsh environment while at the same time fulfilling the purpose of providing bespoke accommodation for a wealthy client. As many early 20th century architects did, Godsell also designed the kitchen and furniture for this house, making it something of a gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. Unusually, Godsell still designs his buildings using old-fashioned tracing paper and pencil, and agrees with Pallasmaa’s comment in his acclaimed book, Eyes of the Skin, that something happens between the head and the hand through the pencil.

A further aspect of Godsell’s work relevant to sustaining identities are his self-funded ‘prototypical housing proposals'. One of these, the Bus Shelter House (2003-04), is a bus stop during the day but turns into a homeless shelter at night (that dispenses blankets, food and water), while the hoarding provides exhibition space for struggling artists. With this project, and the similar Park Bench House, Godsell argues for the creation of what he terms a ‘compassionate infrastructure’ that acknowledges the existence of a transient population in our cities.

Figure 3 - Floating Pool, Jonathan Kirschenfeld, New York, 1999-2007. © Philippe Baumann, photograph courtesy of Jonathan Kirschenfeld

Compassionate infrastructure could easily have been the title of the talk by architect Jonathan Kirschenfeld, whose work is mainly for the non-profit or public sector in New York. In fact, it was called ‘Peripatetic Infrastructure', a reference to the itinerant nature of his projects, particularly The Floating Pool (1999-2007), but also his supportive housing blocks (fig. 3).

At the turn of the last century, floating bathhouses were moored along the East and Hudson rivers in New York so that residents, often from the poor tenement districts, could bathe and learn to swim. The non-profit Neptune Foundation commissioned Kirschenfeld to design an updated version of these bathhouses. Based on the shell of a 260-foot long cargo barge from Louisiana, The Floating Pool has been moored in various New York locations where residents have limited access to pools. Moored at Brooklyn Bridge Park during its eight week first season in 2007, it attracted over 50,000 swimmers.

Although best known for The Floating Pool, Kirschenfeld also spoke about his work on supportive housing projects in New York. These are built on oddly shaped pockets of remnant land in the poorer parts of the Bronx and Brooklyn. Purpose built for mentally ill people, there is an emphasis on creating double-height communal spaces and courtyard gardens. Paradoxically, these low-budget blocks are intended to be anonymous, to fit in anywhere, but are therefore adaptable to their local context. One example is the Marcy Residence, Brooklyn (2001-03), which uses local iron spot bricks (common in New York in the 1930s and 40s), and blends in with the surrounding brownstone houses.

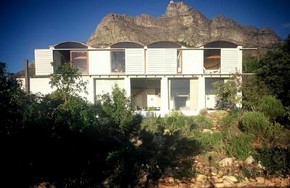

Figure 4 - Die Es, Gawrie Fagan, Cape Town, South Africa, 1960s. Photograph courtesy of Gabriel Fagan

Another architect who provided exemplary examples of buildings that fit into their local context was Gawrie Fagan, whose talk, ‘Cape Identity,’ refers to the Cape Dutch influence on his own architecture. These include his own house, Die Es, Cape Town, which was built by him and his family in the 1960s using limited resources (including a cement mixer he swapped for an old car). His unique and carefully crafted buildings deserve to be better known outside of his native South Africa (fig. 4).

Other speakers included Paul Brislin from Arup Associates, who spoke about the Druk White Lotus School, Ladakh, in the Himalayas, which was built with the local geographic and cultural context in mind. The Chilean architectural practice Pezo von Ellrichshausen spoke about their unique houses and art installations (such as painting all the drain covers pink in Bon Aries). Iñaki Abalos gave a talk about ‘Creating Local Identities’ in Spanish cities and cultural organisations were represented by speakers from UNESCO, Venice in Peril and the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

This was a well-organised and stimulating symposium to a capacity audience, including many architecture students. It addressed important issues in contemporary architecture, but perhaps raised more questions than were answered. A clear definition of what exactly sustaining identities means in architectural practice is still far from clear. But perhaps that is precisely the point: it means many different styles and types of architecture, depending on the local context. It was noticeable that while many speakers criticised the proliferation of computer-designed, so-called ‘iconic’ buildings throughout the world, plonked down in our cities without any thought to their context, no-one seemed prepared to give any specific examples. Sean Godsell made a useful point - anything has got the potential to become iconic – he gave the example of the Australian savoury spread, Vegemite – but, he argued, architects should not deliberately set out to create an icon, that will only lead to ‘stupid buildings'.

Issue No. 3 Spring 2011

- Editorial

- Promoting corporate environmental sustainability in the Victorian era: The Bethnal Green Museum permanent waste exhibit (1875-1928)

- ‘Nothing of intrinsic value’: The scientific collections at the Bethnal Green Museum

- Shedding light on the digital dark age

- John Thomas and his ‘wonderful facility of invention’: Revisiting a neglected sculptor

- Dialogues between past and present: Historic garments as source material for contemporary fashion design

- Kütahya ceramics and international Armenian trade networks

- X-radiography as a tool to examine the making and remaking of historic quilts

- A patchwork panel ‘shown at the Great Exhibition’

- An adorned print: Print culture, female leisure and the dissemination of fashion in France and England, around 1660-1779

- Seating and sitting in the V&A: An observational study

- Review: The Actor in Costume by Aoife Monks

- Review: Not quite Vegemite: An architectural resistance to the icon

- How to submit a proposal to the V&A Online Journal