V&A Online Journal

Issue No. 5 Autumn 2013

ISSN 2043-667X

From Silence: A Persepolis Relief in the Victoria and Albert Museum

Lindsay Allen

Kings College London

Abstract

A recent review of the V&A’s sculpture collection brought to light an unexpected fragment of bas-relief. This unassuming grey rock has an impressive provenance, purporting to come from the Achaemenid site of Persepolis, Iran. In storage since its acquisition in 1916, the fragment is contextualised for the first time in this article, restoring its place in history and its relation to the Museum’s 20th-century collecting practices.

Introduction

During a review of the V&A’s sculpture collection in 2011, an unexpected fragment came to light in the storerooms.(1) Identified in the catalogue as ‘Ancient Persian’, the unassuming stone dates from a much earlier era than most of the collection. The museum’s documents give its origin as Persepolis, a monumental complex developed by the Achaemenid kings between the late 6th and late 4th centuries BC. The relief entered the collection in 1916, and was briefly described in print in 1919 among a mass of objects transferred to the V&A from the Architectural Association, but no image was ever published. The relief may have been exhibited in the year following its accession, but it has not been visible since, and does not feature in any current survey of fragments removed from the site.(2) The purpose of this article is to offer the first examination of the piece, and to investigate its likely context in its probable place of origin. In addition, it will explore how the piece reached the V&A. The relief’s history is only partially recoverable, but casts light on the museum’s curatorial evolution, and contributes to our knowledge of the dissemination of Achaemenid sculptural fragments.

The monumental structures that now constitute the ruins of Persepolis were developed from the reign of Darius I (522/1 to 486 BC) on a natural rock outcrop at the fringe of the Marv Dasht, in the modern province of Fars. Darius had taken over the empire, which by then extended from Egypt to Central Asia, in a confused, violent and probably illegitimate succession in 522/1 BC. The sculpted stone elements of the columned halls of Persepolis accordingly displayed a new and distinctive iconography, which depicted a stable and interrelated hierarchy of king, imperial elite, army and subjects. Echoing and reframing the visual repertoires of preceding Near Eastern kingdoms and empires, Darius’ designers created an inscribed and ornamented architectural court environment.(3) Stone door-frames, columns and foundational elements such as parapet-edged podiums and processional stairways supported a wooden and mud-brick superstructure. After the extensive destruction of the site by Alexander of Macedon in 330 BC, the more vulnerable structural elements began to decay, but the site was never wholly concealed or lost. Some architectural elements were transported from the platform for local prestige building projects at nearby Istakhr and Qasr-i Abu Nasr in the late antique and medieval periods.(4) The documented history of the dispersal of fragments to Europe began with the removal of several small pieces by the artist and traveller Cornelius de Bruijn in 1704 - 5. The stairway parapets and facades presented a multitude of attendants, soldiers and peoples of the empire to those who had the time and resources to break up and transport stone slabs by mule to the Persian Gulf. The first bas-reliefs from Persepolis went on public display in the British Museum in 1818, a few months after the installation of the Parthenon sculptures. A succession of recent British diplomatic missions to Iran had caused a mass exodus of antique stone figures, the bulk of which eventually reached the same museum. A second wave of fragments reached Europe and North America after a period of political instability in the 1920s.(5) The V&A example surfaced in London between these two major phases of fragmentation, so the early links in its anomalous collection history remain, for now, obscure.

The fragment has a maximum height of 19 cm, a width of 24 cm and an approximate depth of 11 cm, although the back is very uneven (figs. 1 and 2). Below a raised, horizontal border, it shows a male head in profile, facing to the right. The veined stone appears to be consistent with the lighter of two grey, cretaceous limestones used in the construction of orthostat bas-reliefs at Persepolis, which were quarried locally.(6) On examination under daylight, the surface has a greyish, mottled, slightly dirty appearance, which may have resulted from the relief’s long-term exposure to London air since the 19th century. Surviving fragments of pigment can occasionally be seen on sufficiently protected pieces of Persepolitan sculpture.(7) Some reliefs acquired and exhibited in the 19th century received surface colour washes in order to manifest the required antique hue. The V&A bas-relief needs further examination to determine whether it retains any signs of having been painted.(8) At present, a small patch of metallic tint is visible on the highest part of the bas-relief, mid-cowl on the figure’s headdress. There are also splashes of white paint around the sides and back of the relief. Both need further investigation, but they resemble traces of modern display and storage environments.

The multi-planed, uneven back also preserves a few impressions of a toothed chisel used to trim the surface during or after the relief’s removal from its original structural context. The relief has no mount and no physical signs of having been adapted for display on a wall. The V&A object number on the back is the only applied sign of registration in a collection. There is no compelling feature that links the piece to a site of production other than Persepolis. Modern, Persepolitan-inspired sculptures do exist, but those that circulated in the late-19th and early-20th century tended to be disassembled structural ornament from 19th-century, elite villas in Iran.(9) Fragments of ancient orthostat reliefs do not exclusively come from Persepolis; in the 20th century, bas-reliefs were excavated at the 4th century ‘Chaour’ palace at Susa, and sculpted stone architectural elements are also found at an increasing number of ‘pavilion’ sites across the Achaemenid heartland.(10) Persepolis, as the most prominent and historically accessible cluster of architectural sculpture, is the most likely source for this relief, the fabric of which visually resembles the stone types used there.

Site Origin

Recontextualizing the fragment in its source site is a challenge, because of the fragmentation of the staircases that protruded above the surface on the Persepolis terrace, especially since the end of the 18th century. The first 19th-century travellers first targeted the massive apadana, or columned audience hall, the façade of which was one of the first features they encountered on ascending the terrace. But by the 1820s, slabs from stairways of the smaller structures further within the site began to be mined. These were often in a more dilapidated state to start with, since the carved slabs had already been, or could be, toppled outwards from their elevated positions. If divided skilfully, each free-standing slab could provide two sets of figures, from its inner and outer faces. In addition, some facade and parapet pieces had already been moved and partially reconstructed at the south-western corner of the platform towards the end of, or just after, the Achaemenid period.(11) Many slabs were therefore already dislocated from their original architectural context. Tracing their removal is difficult without archival testimony, since early drawings focussing on the extant facades do not record in detail the margin of surrounding rubble. In the 20th century, the majority of unexcavated museum accessions of Persepolis fragments came from these smaller structures. The generic anonymity of these uniform stairway bearers and ranked guards, compared to the apadana’s imperial subjects, who were distinguished from each other by their dress, adds to the vagueness that can surround the origin of unexcavated museum pieces.

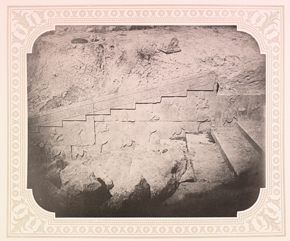

We can guess at the type of structural position of the V&A fragment because of the surviving, raised border above the figure’s head; different decorative terminations topped the parapets depending on their orientation. The outward-facing walls that formed the inner, building-side of each stairway featured these raised, linear borders. Five stretches of these inner walls, which carry attendants facing the same way as our example, border four different stairways that formed the access to two buildings on the platform. These two structures were inscribed by, and are therefore named after, Darius I and his son Xerxes I.(12) The style of the V&A fragment resembles the figures still extant on the inner walls of the south stairs of the Palace of Darius, and those of the east and west stairs of the Palace of Xerxes (figs. 3 and 4).(13) Before the site was extensively excavated in the 1930s, several of these stairways had already suffered heavy loss of sculpture; those leading up to the palace of Xerxes from the east, in particular, offered acquisitive amateur excavators a greater number of angles from which to approach the broken parapets, since they pivoted back upon themselves in a double flight leading upwards to the palace platform (fig. 3). The 1930s Oriental Institute photographs of the north wing of the east stairway of the Palace of Xerxes illustrate how an interior wall figure became vulnerable to removal.(14) The lighter, sharper slab on the upper right, carrying the lion’s haunches and decorative border, is shown in 19th-century prints, and photographs of the 1920s, to have fallen onto the steps below, protecting it and the lower legs of the figures behind it.(15) Above its fallen back, the upper edge of the exposed wall slab was open to both weather and souvenir hunters. The head of the figure on the extreme right, an attendant in a tunic carrying a kid, has been hacked away from the top and the sides, leaving both the kid and the back edge of the figure’s headdress in place.The V&A relief seems to have been removed from an inner stairway wall in a similar fashion, with impact fractures in addition radiating from the points where breaks have been made in the veined, blank rock on either side of the head (figs. 5 and 6). Compared to other stairway figures, that have been reduced to gallery-ready busts by their removal, our example has an irregular shape; it does not seem to have been tidied up for exhibition, something which may be more characteristic of pieces that emerged on the market in the 20th century. By contrast, a comparable robed attendant carrying a covered bowl, this time from the inner face of an outer balustrade, acquired by Yale in 1933, is a crisp and regular artefact (Yale 1933.10).(16) A figure in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with a covered bowl and a headdress that mirrors that of the V&A figure, is framed by a more regular and extensive segment of the decorative interior balustrade, as is a similar piece acquired by the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1933 (LACMA 63.36.17; DIA 31.340).(17) The varying retention of the rosette border above these figures suggests that the portion of the structure sampled by opportunistic raiders was dictated by its overall position on the larger structural slab. Each figure has been transformed into a single-planed ‘art’ object by its removal and display, but the fragments’ margins retain a hint of their former three-dimensional, architectural role.

The museum’s curatorial note and the 1919 ‘Review’ both reported that the V&A relief, ‘apparently comes from the procession which decorated the left-hand side of the middle staircase of the Palace of Xerxes’ and referred to the first extensive photographic survey of the site published in 1882 by Stolze and Andreas.(18) These photographs were not comprehensive, nor were they completely clear, but they were the main reference collection available at the time. Stolze and Andreas plate 20 shows a stretch of stair-climbing attendants on the inner balustrade of the upper southern flight of the east stairs (fig. 7). The slab that comprised the first two figures at the right hand side of the plate is missing in that picture. Published excavation photographs from the 1930s show heavy losses along the edges of the west stairs, particularly on the west-facing wall on the northern side.(19) One of these gaps in either the east or west stairs might be the source of the V&A piece, since the excavator concluded that the attendants there are, like our figure, beardless.

Figure 7 - West stairs, Palace of Xerxes at Persepolis, photograph, Stolze and Andreas, 1870s. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Curatorial notes accompanying the Persepolis fragment, and the 1919 publication, curiously label the piece a ‘Head of a Warrior’. The identification of the figure as a ‘warrior’ must have occurred at a distance from the site, and entailed a certain disregard of the published visual evidence. The headdress of the V&A figure is of a kind that was always shown as part of a riding costume on the reliefs: trousers and a tunic. Yet these stairway figures do not carry weapons, and the tunic costumes alternated with depictions of figures wearing copiously pleated court robes. This kind of pairing is a common feature of Achaemenid iconography, and may allude to the different facets of the Persian elite lifestyle.(20) These alternating, anonymous ‘attendants’ processed up several of the stairways of the smaller palace buildings at Persepolis. Each of these structures, which represent a more intimate environment than the two monumental columned audience halls nearer the entrance to the platform, are associated by their inscriptions with individual kings. The attendants carry draped trays or sacks, kids or lambs, and closed vessels, along the structural margins of these buildings, on both stairways and in windows. Within the main entrances to the buildings, the thresholds are flanked instead by over-life-size figures of the king with servants. The repeated rhythm of pacing figures, lightly patterned with their paired costumes and narrowly varying attributes, defined the directional impetus of the space, involving the viewer in an architecturally-defined movement.(21) The stairways therefore may have led the visitor into a closer encounter with kingship. As a result, the bas-relief figures have been variously interpreted as servants bringing provisions to a royal banquet, or ritual participants attending to a religious duty, both processes that may have been performed in the space within.

In either scenario, the figures represented a perpetual representation of communal resources converging on the person of the king. In this sense, the bas-reliefs represent a parallel iconographic expression of the ongoing management and redistribution of resources attested to in texts found at the site. The so-called Persepolis Fortification Tablets, now held in Tehran and the Oriental Institute of Chicago, contain documentary evidence of the elaborate management of the region’s produce and wealth centred on the king, the royal family and the Persian elite.(22) Rations could be granted to family members, supervisors and governors within the imperial system, work parties of various levels, and to priests for the purpose of maintenance of multiple local cults. The king’s place at the centre of this beneficence in exchange for support was idealised in multilingual royal inscriptions displayed at the nearby religious and royal funerary centre of Naqsh-i Rustam.(23) The bas-reliefs covering the stone platform facades and transitional zones of Persepolis all display the wealth, in manpower and material, at the disposal of the king in this system, a wealth to which each cooperating subject might ideally hope to gain access through their efforts.

Our head has been separated from the body at the top of the shoulder, and the break curves up in front of the figure’s face; no clue in the pose of the arm and no detached snippet of relief give an indication of what he carried. This attribute-loss has eroded his already tenuous and anonymised identity. Decapitation is one of the most common fates suffered by the fragmented parapet and balustrade figures at Persepolis. Faced with the limitations of transport from the inland site, plunderers of sculpture focused on the heads and upper bodies of processional figures. Sometimes, as the topmost layer of separately cut orthostat slabs, these were often the most accessible segments for removal. Over and above convenience, those who chipped at even mid-slab figures focused on heads and faces. An early import to Britain, published by the Society of Antiquaries in 1804, also showed an ‘Antient Head in basso-relievo’, shaped so that it cut the figure off at the shoulder and mid-chest level of a portrait bust; the damaged head, found dislocated from its original position, had also lost its eye.(24) The acquirers’ focus on the figures’ heads perhaps signals a sympathetic or possessive response to the human face as the focus of each sculpture’s identity: an antique trophy. Yet such acts of excision followed on from and mirrored ancient and medieval iconoclasm directed at the destruction of images’ metaphorical power.(25)

The V&A’s curatorial imposition of a ‘warrior’ identity gave the piece a novel military charisma, which differed from these earlier 19th-century receptions of Persepolis. Some of the earliest importations arose from British diplomatic overtures to Iran that stressed protocol, display and the brotherhood of the two kingdoms. A poetic reading of one fragment displayed in a private museum in 1833 stressed the ‘symbols of command’ held in scenes of lost ‘pageantry’. To an imperial ruling class who learned Persian as part of their colonial expertise, Persepolis consisted of the essence of Persia, ‘birth-place of fancy, and romantic dreams’.(26) Later writers observed the objects carried by both imperial subjects and attendants, and interpreted them in the light of the contemporary practice of gift-giving at the Persian New Year. The architect James Fergusson described ‘persons bringing gifts’ on the main audience hall in 1851, and in 1865, Ussher observed only guards and ‘servants bearing in a repast’.(27) By the early 20th century, colonial immersion in Persian literature had lessened, but imperial ghosts remained. The surgeon Sir John Bland-Sutton constructed a miniature ‘apadana’ decorated with copies of Achaemenid columns and walls from Susa as a dining room in his Mayfair townhouse; the structure was demolished in 1932 and one of the thirty-two cast column capitals found its way to the V&A.(28) The ‘warrior’ title bestowed on the relief fragment in 1916 lifted the unassuming stairway figure out of the familiar, hierarchical court context, as it was traditionally understood, to the level of legendary soldiering

Institutional Origin

The Persepolis attendant, or ‘warrior’, first appeared in the V&A’s first hand-list of transfers from the Architectural Association in December 1915, an identification repeated in the published review of accessions, which was drafted in 1917 and published in 1919.(29) The appearance of the relief at the head of the transfer list of 1915 is in fact a relic of the curatorial vision of one of the V&A’s most influential directors, Cecil Harcourt-Smith. Harcourt-Smith had visited Persepolis in 1887, when he took leave from his curatorial role at the British Museum to join a mission to Iran led by the director of the Persian telegraph, Sir Robert Murdoch Smith. Murdoch Smith was already a prolific acquirer of Persian objects for the South Kensington Museum, and wrote a guide to their collection.(30) By 1887, after many years running the telegraph in Iran, Murdoch Smith had already embarked on a second career as Director of the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh. He returned to Iran one last time on a diplomatic mission to secure the future of the British-run communications system there.(31) At the same time, he ensured that the young Harcourt-Smith had enough time away from his work to undertake an appraisal of prospects for archaeological investigation across Iran. At the end of the trip, Murdoch Smith donated six fragmentary pieces of sculpture from Persepolis to his own museum. These joined a series of casts of apadana reliefs dating from the 1820s, and Murdoch Smith supplemented them shortly afterwards with a set of colourful casts of glazed brick panels from the recently-excavated Achaemenid palace at Susa.(32) The Royal Scottish Museum had first developed as a satellite to the South Kensington Museum, but in this respect the London collection’s development echoed that of Edinburgh.(33) South Kensington bought its own set of Susa casts in 1891, but waited several more years for a sample of original bas-relief.(34)

Immediately after returning from the trip, Harcourt-Smith discussed the difficulty of removing sculpture from Persepolis:

The whole platform is covered with fragments of sculpture and architecture which would be easily portable, and a selection of which might be interesting for the illustration of Persian art: if this selection should be required, it can always be carried out at a small expense through the members of the telegraph staff at Shiraz [...] as regards large portions of sculpture it would be a matter of extreme difficulty, if not impossible, to arrange for their transport across the steep, rocky passes which lie between Shiraz and the sea.

He instead recommended to the British Museum Trustees that they commission a new set of plaster casts of the accessible sculptures to supplement the museum’s existing mixture of reproductions and originals.(35) The resulting expedition in 1892 resulted in the plaster casts and a survey plan of the site. Harcourt-Smith wrote a catalogue of the new cast collection, ‘illustrating the art of the old Persian Empire’.(36) And in 1894 and 1895, the British Museum added three further Persepolitan stone relief fragments to its collection, by purchase.(37) In 1913, after thirty-eight years in Iran, the telegraph engineer who had accompanied Harcourt-Smith to Persepolis, J.R. Preece, sold some ‘ancient Persian’ carvings as part of an auction of his own collection. None corresponds to the V&A fragment, and most of them appear to have been 19th-century imitations, but they illustrate the role of the telegraph infrastructure in the movement of artefacts.(38) The V&A relief is conceivably a product of this late-19th and early-20th-century activity.

Harcourt-Smith arrived at the V&A from the British Museum in 1909, but whether he knew of the existence of London’s stray Persepolis fragment before 1915 is unclear. The documentation of the V&A’s acquisition of it in the 1910s is unfortunately the first detectable testimony of the relief’s existence. The Honorary Secretary of the Architectural Association wrote to Harcourt-Smith in October 1915 in order to arrange the transfer to the V&A of items from their unused collection of casts.(39) The Architectural Association had acquired the bulk of its collection in 1904 through the winding-up of the Royal Architectural Museum. Initially founded in 1851 by a loose association of architects led by George Gilbert Scott, the Museum was a lightly-curated conglomeration of intentional acquisitions and happenstance donations intended as a ‘school of art for art-workmen’ in the building trade.(40) As such, it represented a parallel, but ultimately less successful, development to Government Schools of Design that lay behind the South Kensington Museum. The collection included a limited number of classical casts, but the aesthetic emphasis of the densely packed galleries was on medieval and Renaissance architectural sculpture. The Persepolis relief would have already been an unusual presence within this pre-1916 source collection. However, the Royal Architectural Museum’s laconic minute books, which run from the 1850s to 1904, contain no record of the donation of any ancient objects. Guides to the collection written by Scott and later his successor John Pollard Seddon, in 1884, only describe Classical casts and no ‘Oriental’ originals, apart from some carvings from ‘the great desert of Rajpootana [which] are sufficiently representative of the general character of Oriental art, which changes little from age to age’.(41)

In 1915, after Eric Maclagan of the Department of Architecture and Sculpture made an initial survey of the collection in October, Harcourt-Smith wrote to the Association querying the availability of originals as well as casts:

I notice that your letter does not make any reference to the various pieces of original architectural and sculptural work in stone and wood […] in the Tufton Street collection. I should be glad to know what the Council’s views are as to the destination of these originals, some of which would be of great value to us at South Kensington (42)

They replied that they would only earmark both originals and casts that would be ‘of permanent use to our School’ but that they perceived ‘very little difference to the value of the collection from the Museum point of view.’ In the meantime, the Association’s minute books continued to refer to the entire transaction as a transfer of a ‘cast collection’, a term which they seemed happy to use for the entire conglomeration of originals and reproductions (43)

At the end of November, Harcourt-Smith visited Tufton Street in person, accompanied by Maclagan, in order to inspect the division of the collection between those objects to be taken to the museum, and those marked for retention by the Association. The list that was drawn up during the tour records only the chalk-marked objects that would be left behind. Maclagan and Harcourt-Smith noted in writing a mummy case ‘with traces of Painting, Wood, Old writing’ and a ‘Cast of Assyrian stele’, while their gazes rested on the unclaimed pieces in between.(44) In the silence between the wanted artefacts, the Persepolis relief seems to have stood.

Harcourt -Smith wrote formally on 4th December to confirm the transfer of ‘the collection of casts […] together with certain originals’.(45) A handwritten accession list of the originals transferred was quickly typed up by the museum and sent to the Architectural Association for their records. In both copies, the relief was listed first in the list as, ‘Head of a Warrior, gray stone. Probably from the Palace of Xerxes, Persepolis. Ancient Persian’.

In 1916, British military activity in Iran included an encampment at Persepolis by the South Persia Rifles. Travelling southwards from Isfahan to Shiraz on a mission to eliminate ‘marauding German bands’ and to restore order, Sir Percy Sykes visited the tomb of Cyrus at the older capital of Pasargadae, and claimed to have fixed its leaking roof. Then, near Persepolis, he climbed up to and ‘examined with deep reverence’ the tomb of its builder, Darius. Even in the midst of a military campaign, Sykes clearly felt that he needed to represent himself engaging in antiquarian speculation about the imperial past of his field of campaign.(46) An exasperated colleague wrote at the time that Sykes, ‘views himself theatrically as a second Alexander.’(47) For those who ‘served’ in Iran, though, Persepolis was still an important site of colonial memory, which they recalled by means of visiting, inscribing and occasionally taking away with them parts of the site. The emotional investment made by these passing visitors should not be underestimated. In 1884, the recently-widowed Robert Murdoch Smith lost three of his five surviving children in three days to diphtheria, while the family was travelling south towards home. Despite this, his daughter later recalled, he persisted in carrying out a planned excursion to Persepolis, ‘in order that the [surviving] children should take home with them the recollection of a visit to the wonderful ruins of “The Glory of the East”'.(48)

The profile of Persepolis rose again in parallel with a new vogue for ‘Persian Art’ in the late 1920s. From 1931, excavations at the site by the Oriental Institute of Chicago generated plentiful, illustrated press coverage, in which photographs of the bas-reliefs in their original structural context were widely published for the first time. Persepolis casts and original reliefs in Britain and Europe were gathered together in the high-profile, international Persian art exhibition in London in 1931, and in response the British Museum mounted a display with its own collection.(49) Yet, still, the V&A fragment remained invisible. Both institutional and personal memories of the V&A’s Achaemenid holdings had apparently begun to fade; Harcourt-Smith had retired from the V&A in 1924 and had moved on to the royal art collection by 1928.(50)

The fragment now no longer fits easily within the professed curatorial boundaries of the Victoria and Albert museum, which exclude pre-Islamic Middle Eastern sculpture. This prompts us to consider how the meanings of the site on the one hand and the collections on the other have drifted or crystallised since 1916. Persepolis in 1916 was still a universal presence on the cultural horizon, a position it inherited from before the discovery of the Assyrian palaces in the mid-19th century. A young subaltern, an acting captain from the Indian Cavalry, who found himself drinking with a former Oxford don on the verandah of Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo in October 1918, could dream of following ‘the old Susa Persepolis road one day, by Ahwaz, Bebehaw, and Ram Hormuz. He wanted to know if it would take him near the Dashtiarzan Valley, where he had heard there was the best ibex-shooting in Persia.’(51) The early history of the South Kensington collections has been portrayed as an unstable triangulation of ideas of education, art and applied skill, ‘a bazaar or emporium, with new products arriving and departing all the time’.(52) Ironically, the Persepolis fragment arrived in the Museum at a point of redefinition and consolidation, as Cecil Harcourt-Smith defined departmental curatorship by craft and material. As a probable product of British engagement with Qajar as well as ancient Iran in the 19th century, the relief represents a personal and institutional acquisitiveness towards culture that developed alongside industry and empire. Now one of a ‘procession of objects from peripheries to centre [which] symbolically enacted the idea of London as the heart of empire’ the Achaemenid subject, removed from its original hierarchy, became a tributary of the new imperium.(53) The biographical silence before 1915 circumstantially links the piece to a pre-war, 19th-century historical landscape. The V&A’s stray Persepolitan may, therefore, be imaginatively restored to both of its formative eras. Its first was a multilayered court in perpetual motion, evoked in Achaemenid architectural sculpture; in its second, it became both a personal and political, imaginatory and sentimental possession, against a background of fast-expanding historical knowledge.

1. Museum no. A.13-1916. The relief was discovered by Mariam Rosser-Owen of the Asia Department, who first identified the piece, and facilitated my access to it. Ed Bottoms of the Architectural Association shared his knowledge of the archives of the Royal Architectural Museum and Architectural Association, and Miranda McLaughlan of V&A Images gave invaluable support in obtaining new photographs of the relief.

2. R.D. Barnett, ‘Persepolis,’ Iraq 19 (1957), 55-77, L. Van den Berghe, Archéologie de l'Iran ancien (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1959) and Michael Roaf, ‘Checklist of Persepolis reliefs not at the site,’ Iran 25 (1987), 155-8 are subject to ongoing revision; for example, Alexander Nagel, ‘Appendix 1: Catalogue of Selected Relief Fragments from Persepolis in Non-Iranian Museum Collections,’ Colors, Gilding and Painted Motifs in Persepolis: Approaching the Polychromy of Achaemenid Persian Architectural Sculpture, c. 520 - 330 BCE (PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan, 2010) includes some newly-found pieces.

3. Margaret Cool Root, The King and Kingship in Achaemenid Art, Acta Iranica Textes et Mémoires, vol. IX (Leiden: E.J. Brill:, 1979).

4. Ann Britt Tilia, Studies and restorations at Persepolis and other sites of Fars, vol. 1 (Rome: IsMEO, 1972), 54-5, 262; Charles K. Wilkinson, ‘The Achaemenian Remains at Qaṣr-i-Abu Naṣr,’ Journal of Near Eastern Studies 24, 4 (1965): 341-5; André Godard ‘Persépolis: Le Tatchara,’ Syria T. 28, Fasc.1/2 (1951): 68.

5. Cornelius de Bruijn, Travels into Muscovy, Persia, and part of the East-Indies. Containing an accurate description of whatever is most remarkable in those countries (London: 1737), vol. 1, Preface and vol. 2, figs. 137-42; on the ‘excavations’ of 1811 behind the first public display, see John Curtis ‘A Chariot Scene from Persepolis,’ Iran 36 (1998): 45-51; the post-1920s exodus occurred via dealers and is more difficult to trace: Lindsay Allen, ‘The Persepolis diaspora in North American museums: from architecture to art’ (paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research, New Orleans LA, USA, November 18 - 21, 2009), e.g. Ananda Coomaraswamy ‘A Relief from Persepolis,’ Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts XXXI, 184 (1933): 225.

6. Ann Britt Tilia, ‘A study on the methods of working and restoring stone and on the parts left unfinished in Achaemenian architecture and sculpture,’ East and West 18 (1968): 67-95; Ann Britt Tilia, Studies and restorations at Persepolis and other sites of Fars, vol. 1 (Rome: IsMEO, 1972), 243 n. 3; Tracy Sweek and St John Simpson, ‘An unfinished Achaemenid sculpture from Persepolis,’ The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin (London: British Museum Press, 2009): 83-8.

7. Alexander Nagel, Colors, Gilding and Painted Motifs in Persepolis: Approaching the Polychromy of Achaemenid Persian Architectural Sculpture, c. 520 - 330 BCE (PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan, 2010); Janet Ambers and St John Simpson, ‘Some pigment identifications for objects from Persepolis,’ ARTA 2005.002 (January, 2005): 1-13.

8. In 1917, the author of the acquisitions summary in the museum ‘Review’ was alert to traces of colour on the medieval fragments, but no visible colour was noted on the relief itself, [Maclagan] ‘Sculpture,’ Review of the principal acquisitions during the year 1915 (Westminster: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1919).

9. Judith Lerner, ‘Three Achaemenid ‘Fakes’: a Re-evaluation in the Light of 19th century Iranian Architectural Sculpture,’ Expedition (1980, winter): 5-16.

10. A. Labrousse and R. Boucharlat, ‘La fouille du palais du Chaour à Suse en 1970 et 1971,’ Cahiers de la Délégation Archéologique Française en Iran 2, 61-167; Wouter Henkelman, ‘The Achaemenid Heartland: An Archaeological-Historical Perspective,’ in A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, ed. D.T. Potts (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 931-962.

11. A site known as ‘Palace H’ containing parts from an earlier ‘Palace G’ and others: Ann Britt Tilia, ‘Recent Discoveries at Persepolis,’ American Journal of Archaeology 81, 1 (Winter, 1977):77; Ann Britt Tilia, Studies and restorations at Persepolis and other sites of Fars, vol.1 (Rome: IsMEO: 1972), 253-258.

12. i) Palace or ‘tachara’ of Darius I, southern stairway, west flight, northern wall: Erich Schmidt Persepolis, vol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), pl.134A & C; ii) Same structure, west stairs, north flight, eastern wall: ibid., pl. 152 & 156D; iii) Palace of Xerxes I, western stairway, north flight, eastern wall: ibid., pl. 163A; iv) Same structure, eastern stairway, lower south flight, western wall: ibid., pl. 169A; v) Same structure, eastern stairway, upper north flight, western wall: ibid., pl. 168A. Reused ‘attendant’ reliefs also featured in the structure of ‘Palace H’, Ann Britt Tilia, Studies and restorations at Persepolis and other sites of Fars, vol.1 (Rome: IsMEO, 1972), figs. 95 & 152.

13. For the relative dating of these structures, see Michael Roaf, ‘Sculptures and Sculptors at Persepolis,’ Iran XXI (1983): 138-141.

14. Erich Schmidt, Persepolis, vol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), pl. 169.

15. Eugene Flandin and Pascal Coste, Voyage en Perse (Paris: 1851), pls. 132 and 134.

16. ‘T.S.’, ‘A Relief from Persepolis,’ Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University, vol. 6 (1933): 6-8.

17. A. Mousavi, Ancient Near Eastern Art at the Los Angeles Museum of Art (Los Angeles: 2013); E.H. Peck, ‘Achaemenid Relief Fragments from Persepolis,’ Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 79, 1/2 (2005): 20‐33.

18. F.C. Andreas and F. Stolze, Persepolis, die Achaemenidischen und Sasanidischen Denkmäler und Inschriften von Persepolis, Istakhr, Pasargadae, Shahpur, vols. 1 and 2 (Berlin: 1882).

19. Erich Schmidt, Persepolis, vol.1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), pl. 163A. A ragged break across the torso of the fifteenth figure from the bottom in this plate shows the kind of partial removal that occurred in our case.

20. Margaret Cool Root, The King and Kingship in Achaemenid Art, Acta Iranica Textes et Mémoires, vol. IX (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1979), 279-282. The tunic and trousers costume is sometimes referred to as ‘Median’ due to its similarity to the costume worn by those ethnic representatives on some of the reliefs.

21. Sophy Downes, The Aesthetics of Empire in Athens and Persia (PhD dissertation, University of London, 2011), 97 and 103.

22. Pierre Briant, Wouter Henkelman and Matthew Stolper eds. L’archive des Fortifications de Persépolis, Persika 12 (Paris: Éditions de Boccard, 2008).

23. On benefit envisaged in royal encounters see Lindsay Allen, ‘Le roi imaginaire: an audience with the Achaemenid king,’ in Imaginary Kings: Royal Images in the Ancient Near East, Greece and Rome, Oriens et Occidens 11 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005).

24. Strachey, An Account of a Profile Figure in Basso Relievo, from the Ruins of Persepolis, in a letter from Richard Strachey, Esq. In the Suite of Captain Malcolm (London: 1804) British Museum Prints and Drawings 1880, 0110.127). The relief was sold at auction in 1986, and its current whereabouts are unknown.

25. Zainab Bahrani, ‘Assault and Abduction: the Fate of the Royal Image in the Ancient Near East,’ Art History 18, 3 (1995): 362-382.

26. William Park, The Vale of Esk (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1833). 25. The fragment in question was sent back to his family home by Sir John Malcolm in 1810 and is now in the National Museum of Scotland (1950.138).

27. James Fergusson, The Palaces of Nineveh and Persepolis restored; an essay on ancient Assyrian and Persian architecture (London: 1851); John Ussher A Journey from London to Persepolis (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1865), 540.

28. Victor Bonney, ‘Sutton, Sir John Bland, first baronet (1855–1936),’ rev. Roger Hutchins, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36377 [accessed 15 March 2013]. Bland-Sutton’s inspiration was more biblical than classical, since Susa was most famous as the setting for the drama of the Book of Esther. The unnumbered V&A cast is one of at least two pieces to survive, the other being in the British Museum (object no. 122136A), see Simpson, ‘Cyrus Cylinder: Display and Replica,’ The Cyrus Cylinder: the king of Persia’s proclamation from ancient Babylon, ed. I. Finkel (London: IB Tauris, 2013), 83 n.1 and fig. 26.

29. [Maclagan] ‘Sculpture’, Review of the principal acquisitions during the year 1915 (Westminster: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1919), 2.

30. R. Murdoch Smith, Persian Art (Pub. for the Committee of Council on Education by Chapman and Hall: London, 1876); Denis Wright, The English Amongst the Persians during the Qajar Period 1787 - 1921 (London: Heinemann, 1977), 134-5.

31. R. Stronach, ‘Smith, Sir Robert Murdoch (1835 - 1900),’ rev. Roger T. Stearn, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: 2004), www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/25896 [accessed December 14, 2011]; M. Rubin, ‘The Telegraph, Espionage, and Cryptology in Nineteenth Century Iran,’ Cryptologia 25:1 (2001): 23.

32. Persepolis fragments: object nos. 1887.566-571, Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art (now National Museums Scotland) Register of Museum Specimens, 1884.80.315R to 1888.410, 291f. Nos. 568-571 were sold during and just after the Second World War. At least one of the fragments came from the south-west corner of the site, which Cecil Harcourt-Smith described in detail in his report. For the rest of the ‘Achaemenid’ collection in Edinburgh, see Major-Gen. Sir R. Murdoch Smith, Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art: Guide to the Persian Collection in the Museum (Edinburgh: Stationery Office, 1896), 6.

33. On the administration of the Departmental Museums from South Kensington, see Clive Wainwright, ‘The making of the South Kensington Museum I: The Government Schools of Design and the founding collection, 1837 - 51,’ Journal of the History of Collections 14 (2002), 6.

34. For the response to these walls in Paris, see Alexander Nagel Colors, Gilding and Painted Motifs in Persepolis: Approaching the Polychromy of Achaemenid Persian Architectural Sculpture, c. 520 - 330 BCE (PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan, 2010), 81.

35. British Museum, archives of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Minute Books, report of Cecil Smith Oct 6th 1887, 127. On the results of his recommendations, see St John Simpson, ‘Bushire and Beyond: Some Early Archaeological Discoveries in Iran,’ in From Persepolis to the Punjab, ed. Elizabeth Errington and Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis (London: British Museum Press, 2007), and Herbert Weld Blundell, ‘Persepolis,’ Transactions of the Ninth International Congress of Orientalists (London, September 5 - 12, 1892) vol. II (London: 1892), 537-59.

36. Cecil Harcourt-Smith, Catalogue of Casts of Sculptures from Persepolis and the neighbourhood, illustrating the art of the old Persian Empire, from 550 - 340 B.C. ( London: Harrison & Sons, undated).

37. Terence C. Mitchell, ‘The Persepolis Sculptures in the British Museum,’ Iran 38 (2000): 53.

38. J.R. Preece, Exhibition of Persian Art & Curios: The collection formed by J.R. Preece… at the Vincent Robinson Galleries (London: 1913)

39. V&A Archive, MA/1/A772/8, nominal file: Architecture Association.

40. Ed Bottoms, ‘The Royal Architectural Museum in the light of new documentary evidence,’ Journal of the History of Collections (2007): 1-25.

41. Seddon did not mind the lack of Oriental models, because ‘the character of this Oriental art has always been conventional and stereotyped […] and divorced from that intellectual freedom which has been the mainspring of the arts in the West.’ J.P. Seddon, Caskets of Jewels: A Visit to the Architectural Museum, Our own casket (Westminster: Published at the Architectural Museum, 1884).

42. Royal Architectural Museum archives, 03/03/01.

43. V&A Archive, MA/1/A772/8, nominal file: Architecture Association. Letters of 12 and 16 November, 1915.

44. Archaeological Association Minute Book, 1913 - 1916.

45. V&A Archive, MA/1/A772/8, nominal file: Architecture Association.

46. Percy Sykes, ‘South Persia and the Great War,’ The Geographical Journal, 58 (1921), 106-107.

47. ‘with a dash of Kitchener.’ Clarmont Skrine, quoted by Antony Wynn, Persia in the Great Game: Sir Percy Sykes, Explorer, Consul, Soldier, Spy (London: John Murray, 2003), 270. Persepolis was previously ‘occupied’ by British Indian forces during 1911 - 12 in the wake of unrest in Shiraz and Isfahan, Ibid., 253. A large graffito commemorates the Central India Horse on the monumental gateway.

48. W.K. Dickson, The Life of Major-General Sir Robert Murdoch Smith KCMG (Edinburgh and London: Blackwood & Sons, 1901), 295.

49. Royal Academy of Arts, Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Persian Art, 2nd edition (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1931), 5, cat. 2. The exhibition included a new fragment donated to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1927: R. Nicholls and M. Roaf, ‘A Persepolis Relief in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge,’ Iran, 15 (1977): 146-152. On the British Museum’s galleries, see S. Simpson, ‘Cyrus Cylinder Display and Replica,’ in The Cyrus Cylinder: the king of Persia’s proclamation from ancient Babylon, ed. I. Finkel ( London: IB Tauris, 2013), 69-84.

50. J. Laver, ‘Smith, Sir Cecil Harcourt- (1859 - 1944),’ rev. Dennis Farr, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/33694 [accessed January 5, 2012]

51. A Correspondent, ‘The Adventurous East: Lions and Men,’ The Times, October 3, 1918, 11 column C.

52. Bruce Robertson, ‘The South Kensington Museum in context: an alternative history,’ Museum and Society 2 (2004): 9.

53. Tim Barringer, ‘The South Kensington Museum and the colonial project,’ in Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, ed. Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn (London: Routledgel, 1991), 11-12.

Issue No. 5 Autumn 2013

- Editorial

- Sacred Space in the Modern Museum: Researching and Redisplaying the Santa Chiara Chapel in the V&A’s Medieval & Renaissance Galleries

- From Silence: A Persepolis Relief in the Victoria and Albert Museum

- Finding the Divine Falernian: Amber in Early Modern Italy

- Le Brun’s ‘Study for the head of an Angel in the Dome of the Château de Sceaux’: A Consideration of Connoisseurship and Collecting in 18th-Century France

- ‘La Chapellerie’: A Preparatory Sketch for the ‘Service des Arts Industriels’

- How to submit a proposal to the V&A Online Journal